Twisted Intimacies: A Conversation with Susan Streitfeld

In Susan Streitfeld’s electrifying erotic drama Female Perversions (1996), a star attorney named Eve (Tilda Swinton) receives the news that she has been nominated for a judgeship at the same time that her life spirals out of control. After years of performing professional excellence in high heels and skirt suits, she finds her balancing act suddenly menaced by personal problems that play out over the course of a few days and are depicted in a series of uncanny, at times disarming vignettes: her sister Maddie (Amy Madigan) is thrown in jail for shoplifting, forcing Eve to intervene and do damage control; her boyfriend, through whom she feeds her sexual fantasies of domination and submission, is away on business; a younger, supercilious female attorney is preemptively hired in anticipation of Eve’s departure from the firm. Meanwhile, haunting, elegantly stylized dream sequences visualize the protagonist’s most primal erotic urges, underscoring the chaos rumbling beneath her pristine facade.

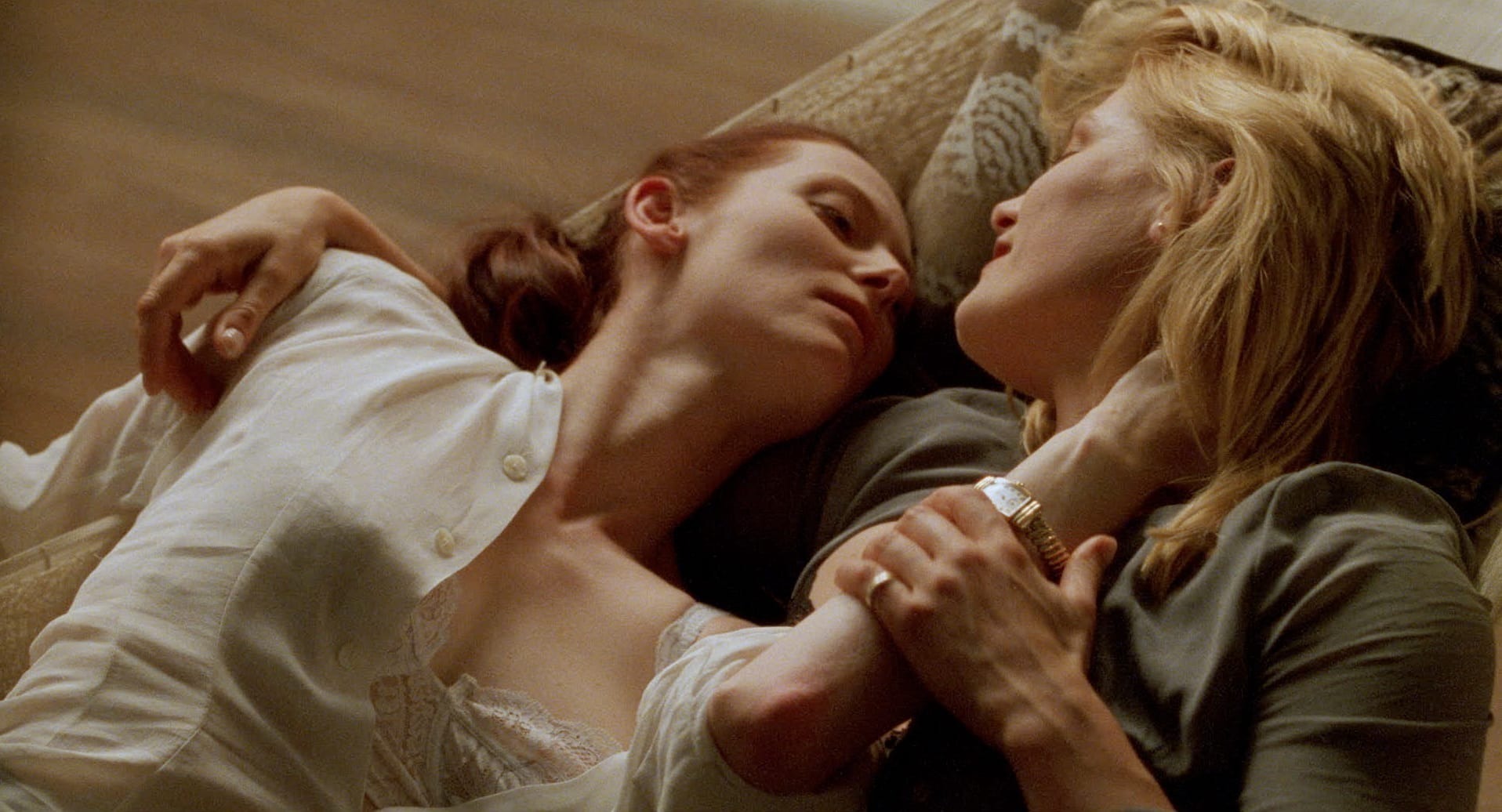

Eve is not the only character projecting a highly curated version of herself. In Maddie’s home, Eve meets a group of women—including a sex worker and a deluded romantic—who represent parodies of womanhood, forcing Eve to question her own supposed normalcy. The complexity of her desires is revealed in a romance she strikes up with a female doctor, a relationship whose strictly physical nature exposes Eve’s compartmentalized approach to intimacy.

Despite its title’s suggestion of titillation, Female Perversions breaks down its heroine’s inhibitions with empathy and gravity. It does so while presenting a disturbing, seductive, and refreshingly droll portrait of the ways in which women enact power and femininity to feel at ease in a world dominated by men. Based on the Freudian psychologist Louise Kaplan’s book Female Perversions: The Temptations of Emma Bovary (1991), the film is an independent production, written and directed by a first-time filmmaker, that takes seriously the psychic textures of female consciousness, in turn urging us to break free from the behavioral prisons we create for ourselves.

To celebrate Female Perversions’ streaming premiere on the Criterion Channel, I spoke to Streitfeld about the film’s sexual politics and recent resurrection.

Despite the abundance of erotic dramas released in the nineties in the U.S., Female Perversions seems to exist on its own wavelength. I’m guessing this is in part because you don’t come from a Hollywood/commercial filmmaking background. Can you talk about your artistic development and your work leading up to the film?

I studied the fine arts, specifically painting, at Syracuse University before taking a sharp pivot and moving to Mexico. There, I was introduced to Latin American literature, which helped me understand how to tell a story and drew me to fusions of the real and fantastic. I didn’t grow up watching TV or going to the cinema, but in Mexico I became friends with a woman whose brother was a cinematographer, which opened up a whole new world for me. When I came back to the States, I went to NYU film school. Watching European films around the city was my cinematic training. Sometimes I’d do two double features a day. It’s hard to express just how much those screenings impacted me, because nowadays we’re dealing with loads of visual input from social media and our phones. Back then our television sets were tiny, so we dragged ourselves to the cinema, and what we saw there held enormous sway over us.

Later I went to LA for a spell and realized it was not where I should be as someone who was wanting to find a way into independent filmmaking. At a loss, I decided to try my hand at the theater, so I began teaching it and directing plays. Eventually, I found my way back into the film industry working as an agent. I didn’t aspire to become one but I fell into it because I was plugged into European film and knew there was a pocket that needed to be filled in terms of representing European talent in the States. I represented Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, and Colin Firth on a few projects.

What attracted you to Louise Kaplan’s book Female Perversions: The Temptations of Madame Bovary that made you want to adapt it? It’s a massive literary/psychological study, so I wonder how you first went about translating its ideas into a fictional narrative.

My father was a shrink, so the psyche—what enables and shapes our behavior—is always something I’ve been fascinated by. When Kaplan’s Female Perversions came out in the early nineties, I was immediately drawn to it and started developing a plot to anchor its ideas. Everything can be looked at on a scale of perversion. Perversion has become a label for a certain type of behavior that’s not normal, but for me it’s about how we perform normalcy, or what we do to maintain normalcy. We’re all engaged in perverse behaviors, because they help us get from point A to point B. There are no characters in the book, but there are types, so we created characters based on these modes of perverse behavior. You have Eve’s sister, Maddie (Amy Madigan), who is a kleptomaniac. Emma (Laila Robins), Maddie’s roommate, is a caricature of femininity, a personification of homeovestism. You have Emma’s sister (Frances Fisher), who is a stripper. Eve (Tilda Swinton) is a “normal” character, so the story became about breaking down and questioning her supposed normalcy. We’re all perverse, but some days we’re more perverse than others. Perversion is a strategy.

Were the erotic dream sequences, which involve ropes and masked figures, informed by the book?

The distributors and some of the reviewers didn’t like the dream sequences, but those parts are key to what Louise is trying to get at in the book, in terms of where our perverse behaviors come from. The artist John Byrne, who was Tilda’s partner when we were making the film, created the mural that is in the backdrop of the first fantasy sequence. He based it on the paintings of mostly female figures I’d done over the course of working on the film. My paintings at the time were inspired by my own dreams, so the look of Eve’s fantasies come from the deepest parts of my being.

In superficial ways, Female Perversions and its sexually adventurous career woman protagonist seems to fit into the erotic thriller genre popular at the time, but I ultimately see it as a film that dismantles those tropes and stereotypes. Was this something you had in mind?

I’m not interested in pushing the boundaries of sex on-screen. Instead, I’m asking, why is Eve doing what she’s doing? What is going on in there that she behaves the way she does? It’s a dance between the conscious and the unconscious, but our unconscious—the part we don’t see—is the real driver. I don’t really believe in genres. The minute we start thinking in categories, we start thinking in terms of what is and what isn’t. In this sense, the industry hasn’t moved that far. Think of something like Anora—every piece I’ve read claims it’s not Pretty Woman, but it absolutely is. The fact that people can’t see this speaks to a blindness we have, or a delusion that we’ve advanced just because some elements have changed. I don’t have an opinion about what’s pornographic or not, because that’s just a category. I’d personally rather see less nudity because it’s more erotic to see less. But that’s just my taste.

Can you tell me a little bit about casting Tilda Swinton as Eve?

Tilda was not on my radar while I was writing the script. The only person I had in mind was Amy Madigan, who is a dear friend and whom I had worked with as a theater director. I couldn’t find an American woman who wanted to play the role of Eve, but I had to get some kind of name, because otherwise it would’ve been impossible to sell the film. Having been an agent with strong connections to the UK, I was able to float my script around London. Tilda was one of the actresses I met, and at first I thought she was too young. She also thought she was too young. But our chemistry was terrific. I remember sitting in a hotel bar in London and feeling like our foreheads were becoming glued together. Eve was supposed to be the older sister, so when Tilda came on board, we simply made her the younger one.

Eve is an incredibly complex character. She can command a courtroom and play a dominant role when she has sex with her boyfriend, yet we also see her lose it completely, as in the scene when she smears lipstick on herself. Can you talk about how you developed the character and the kinds of work Tilda did to get into character?

Tilda came out to LA for three months before we started shooting the film. She had to work with a voice coach to nail the American accent, which she had never done before. Years later, Tilda received a Supporting Actress Oscar for Michael Clayton, in which she plays an American attorney. I saw Eve all over that character, and I like to think Female Perversions helped her triumph in that role. Our rehearsals took place in the middle of the O. J. Simpson trial. We talked a lot about one of the prosecutors, Marcia Clark, and how the media was fixated on her clothes, lipstick, and hair. We heard very little about the points she was making in the case. Whatever space you go into, whether it's the courtroom or the offices of Criterion, there are rules. You’re navigating what the people around you want and what your job is and how you want to present yourself. Female Perversions is about underscoring this process of navigation, which is a kind of psychological dance. I’m a big believer in rehearsals because I have a background in theater and worked with John Cassavetes, so our rehearsal time was incredibly important in developing the facets of this internal landscape.

In what context did you work with John Cassavetes?

One of my theater students was Nick Cassavetes, the son of John. He had watched a play I had done in LA for a small theater and was so impressed by it that he invited his parents. So I have this wonderful memory of standing in the back of the theater watching John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands watching my work. Long story short, John ended up choosing me to direct his play East/West Game, and I cast Nick in a role. It was a privilege seeing the way John dealt with the material. A Woman Under the Influence was in theaters when I was a student at NYU, and he really stood out to us as the one big American independent filmmaker. When we were developing the play, we would take long walks every night and rewrite the third act over and over again.

The nineties are considered a watershed decade for independent filmmaking, so I wonder if you felt there was something unique or exceptional about the resources and artistic license you were given and/or the film’s means of production?

We had twenty-four days and a six-days-a-week set. The budget came down to something like two million dollars, and we did not go over. We had no one watching over us. It wasn’t planned this way, but the crew was made up of mostly women: the producer, production manager (Rana Joy Glickman, who left a Quentin Tarantino film to join us), cinematographer, production designer (Missy Stewart, who worked on To Die For [1995]), composer (Debbie Wiseman, who went on to have an illustrious career in the UK). At times, Female Perversions felt more like a movement than a film.

The film the distributors thought they were getting is not the film they got, but it was too late because I refused to do reshoots. They tried to come in and do their own edit, but we held our ground, and it worked because Tilda was essentially carrying the foreign-sales market on her back. Zalman King, who was an executive producer, also helped. So it was a matter of figuring out our levers of power to keep the vision as intact as possible—and we ultimately lost very little at the end of that editorial power struggle.

Because the film deals explicitly with women’s sexuality and power, the costume design strikes me as particularly important. Can you talk a little bit about dressing Eve, who wears these amazing power suits (which, toward the end of the film, Maddie mocks and corrupts)?

We were fortunate because Tilda, who was already a fashion icon at the time, had a lot of strong relationships with people in the fashion industry. So we were gifted the Manolo Blahniks that Eve wears and that you see on one of the film’s posters—that image also became the cover for the republished version of the book. Actually, the costume designer who conceived Tilda’s outfits was Bella Freud, the great-granddaughter of Sigmund Freud and daughter of Lucian Freud. She knew Tilda—they’re roughly the same age—and she made a few short films herself. She was perfect because her sense of humor came through in the costume design while still creating something very chic. The suits that women need to wear in places like courtrooms and offices are typically very stiff, but Bella tweaked Eve’s a bit, made them a bit shorter—a tuck or a flip here and there that reveals latent dysfunctions.

This sense of humor runs through the entire film!

Laughing at ourselves is a radical thing. I’ve always been on the margins; it’s where I prefer to be. And when you’re there I think you tend to develop a sense of humor about how you exist in the world, especially when it comes to social norms. You start seeing double entendres everywhere.

Are you surprised that Female Perversions has found a new life in 2025? In some ways, the social landscape in terms of women’s rights and the state of feminism is quite different, though in other ways, it’s not . . .

A shiver goes down my spine when I see the film described as a “feminist classic.” It makes me feel like we’re pretending—gone there, done that, and now this can be a classic . . . which is horrifying. The truth is these issues are still very active. We have to take seriously this urge to transform and become free, because these urges determine how we live our lives. Our fantasies are important. We need to address them because they fuel us, and they’re things that are created in response to how we exist and make sense of ourselves and our identities within a collective.

The end of the film, when Eve is cradling Edwina [the young girl who lives in her sister’s shared house], is key to the film’s ethics—and, I think, its continued relevancy. The opening quote by Louise Kaplan basically says that if we keep on trying to fit ourselves into the order of the world, we’ll confine ourselves to the bondage of normal femininity—a perversion, if you will. What we lose as a result is intimacy; our ability to love and be authentically in touch with other human beings. In this sense the film is a warning that if we keep going on with this dance, if we keep flinging ourselves back and forth from control to no control to control, we will never become truly vulnerable. We will not help that child. We will not notice the genocide. What are we doing besides trying to protect ourselves?

More: Interviews

Near and Far: A Conversation with Dwayne LeBlanc

The director of Civic and Now, Hear Me Good talks about how his experience as a first-generation Caribbean American and his love of Chantal Akerman’s short La chambre have influenced his work.

First and Foremost: Rógan Graham on Black Debutantes

The critic and curator talks about working on a program of films by trailblazing Black women directors, which opened at London’s BFI Southbank this year and is now playing on the Criterion Channel.

The Other Side of Apocalypse: A Conversation on We Were the Scenery

In this Sundance-award-winning exploration of war and memory, writer Cathy Linh Che shines a spotlight on her parents, who were Vietnamese refugees living in the Philippines when they were cast as extras in Apocalypse Now.

The Banality of Apartheid: A Conversation with Milisuthando Bongela

In her intensely personal debut feature, the filmmaker and poet investigates the myths that have shaped South African history through a mix of archival footage, poetic remembrances, and conversations with friends and family.