It’s not easy for anybody to get a film made, regardless of their background. But looking at the lengthy IMDb credits of many male filmmakers in comparison to their female counterparts can bring into sharp focus the disparity in opportunities afforded. This discrepancy becomes all the more apparent when looking at statistics around specific demographic groups. In May 2025 at London’s BFI Southbank venue, the South London–based critic and curator Rógan Graham presented a thoughtful response to this issue with Black Debutantes, an ingenious and popular program that grouped together the work of trailblazing Black women filmmakers who made an impact with their first—and in some cases only—feature film. Instead of focusing on what might have been, Graham asked viewers to celebrate and deeply engage with these stylistically and thematically heterogeneous, often overlooked works, and to consider them in dialogue with one another.

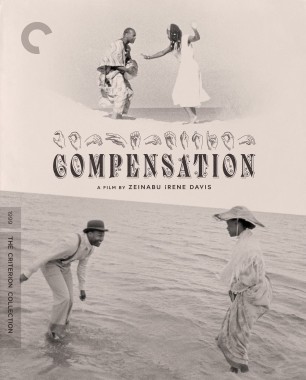

I was moved and excited by the idea of the program, and, in my role as Criterion’s curatorial director, was keen to collaborate with Graham to bring a version of Black Debutantes to the Criterion Channel. After all, a number of suitable films, including Cheryl Dunye’s sparky lesbian meta-comedy The Watermelon Woman (1996), Cauleen Smith’s idiosyncratic coming-of-age drama Drylongso (1998), and Zeinabu irene Davis’s unclassifiable indie classic Compensation (1999), have entered the Criterion Collection in recent years, and would benefit from this fresh and thoughtful contextualization.

Shortly before Black Debutantes launched on the Criterion Channel this month, Graham and I sat down to discuss the philosophy behind her program, her experiences presenting these works in public, and some of her favorite first features by Black women directors.

What was the genesis of this curatorial framework for you?

I’ve always been interested in the work of women filmmakers and Black filmmakers. As I was going through Black women filmmakers’ individual filmographies, I realized that some of them were very short, or singular, when it came to feature films, and I started drawing those connections.

There are themes of coming-of-age and girlhood in a lot of the films, but stylistically they’re very different, and the legacies that the films have are very different. And the legacies and careers of the filmmakers went in the directions they did for very different reasons too. The curatorial framework was about not wanting to oversimplify, or speak in too broad brushstrokes about how certain things played out, but to just look at the quality of the films—because they’re wonderful—and attempt to connect them more broadly with audiences.

In developing this program, was there any sense of pushing back against the traditional presentation of auteurism as a male thing? Does it trouble you that it’s so much harder to have this auteurist conversation around Black female filmmakers?

I’m a massive Michael Mann fan and a massive Martin Scorsese fan. I don’t come from a film family, but Scorsese was the first director’s name I knew. When you’re starting out, you don’t pay attention to the director, you pay attention to who was the star of the film. It was like, oh, there is someone behind this. Initially, going into the Black Debutantes project, when I did discover more and more names of Black women directors who had short or singular filmographies, there was an initial spate of anger, I suppose—a feeling of being deprived, as a film fan, of what more these women could have accomplished: a feeling of grief for them. Eventually, as time progressed, I felt that it was not my place to have these feelings, because there are so many complicated reasons behind these stories. That’s not to let the industry off the hook, but there are very personal reasons why these filmmakers chose to continue their career in a particular direction or not, or had the opportunity to, or wanted to be creative and express themselves through different mediums beyond feature filmmaking. I don’t want to act like that is the be-all and end-all. So, once I’d worked through those feelings of anger and grief—and maybe that sounds a bit extreme—I realized it’s not my place to say what’s tragic or not. It’s my place to say, “Have you seen this? You should probably see this.” And that’s where I’d resolved to get to by the time the program launched in May.

It is a complicated thing to metabolize these feelings, though, isn’t it? They can sneak up on you, for example, watching Daughters of the Dust (1991), and realizing that not only was it the first feature film by a Black woman to receive a theatrical release, it’s the sole film made by Julie Dash to have a theatrical release.

Yes, and I’ve spoken to some of the filmmakers—including Naked Acts director Bridgett M. Davis, who has herself written about her film’s rerelease in the States, for SEEN magazine—about that anger and deprivation. But I’m hoping that increased engagement with the work, within this framework, allows the filmmakers to speak for themselves, or leads to them wanting to speak for themselves. A strange thing can happen when you encounter a film when it has an anniversary or a restoration, and it almost exists outside of the context of the filmmakers’ contemporaries or the movement it was working in—not always, but oftentimes. And that film is put on a pedestal until the next year rolls around and something else is plucked out. I think—or hope—that putting these particular works and filmmakers in the context of one another will open up more conversation. And the filmmakers can be alongside their contemporaries, whereas in the past they may have been pitted against one another—because many of them were working in the 1990s—for funding. And the same goes for audiences too. It’s not like you see one film, and you’re deprived, not knowing where to look next for something similar. It’s right there.

What were some of the key takeaways you had from discussing these films and this program with audiences?

The one thing that’s stuck with me—and I think about it whenever I think of Naked Acts now—is a member of the audience coming up to me after the screening and saying, “I’m sixty years old, and I’ve waited sixty years to see that film.” She explained that she is not a big film fan or a regular cinemagoer, but she’d heard about the program and thought to herself: I’ll give it a go, I’m a Black woman, let me see what this is about. It was really meaningful for me to connect with audiences who didn’t consider themselves cinephiles, to hear intergenerational feedback and the dialogues I was privy to, and to watch the way audiences changed from early in the month to later in the month. Looking around, you could see more younger people, more Black people, and lots more older Black women attending by themselves, which is something I don’t often see when I go to the cinema. That’s going to be me one day. Seeing that was really powerful. These films feel honest to life, and, for the most part, to how Black women move through the world—and it’s often working-class women.

When it came to the physical space of watching the films, having an audience that was reflective did really matter to me—making sure the films were reaching the right people, so that the older Black woman sitting by herself can receive the film comfortably, and receive the heavy themes, or the lightness, or the familiarity, in a space that feels safe. There’s nothing worse than experiencing something that can feel honest, abrasive, and really penetrate you and your experience and your life, and not feeling safe enough in your physical environment to receive it. But I tried to take as much of that into consideration as I could.

Can you speak about interacting with the filmmakers?

Feedback from the filmmakers was important. There were some I had relationships with—or was building relationships with—and some who were approached by the BFI. I thought to myself, I really hope I’ve got this framing right, because I didn’t want it to be an insult. Maybe I was overthinking it, but I felt that there was a risk of “poor them, and now I’m giving them new life,” which is just not . . . I was coming from a real place of excitement, thinking all of this work is amazing, and look, you get to see it all! I wanted that to be conveyed. That has been the case with the filmmakers I have interacted with, and I hope it continues to be the case in this new, updated iteration.

How did you conceive of the chronological makeup of the series? There are some newer titles in there, like Dionne Edwards’s Pretty Red Dress (2022), but a lot of the program comprises work from the 1970s through the ’90s.

That was really interesting to me. I thought to myself, should I narrow it and make it about specific years? But then I was just like, no, because I’d be cutting off this, that, and the other. The initial concept was going to be centered on Black women filmmakers who have only made one theatrically released feature, and then I broadened it out and included films by directors who’ve made more than one film. That gave me license to include some more contemporary work, and, with the BFI program, I was looking at titles that didn’t have UK distribution to bolster awareness of them. But more than the years or eras of the films, I was conscious of how American the program is. And I think I still am. But then you just look at what is available and ready to be screened—and screened properly in terms of licensing, and making sure the right people are paid—and it gets narrower. Who has the infrastructure to preserve film and care for it, and which filmmakers are alive? All of these logistics come into it, and it’s America that has the most presence. I am conscious of it still, but it is what it is.

Can you tell me about some of the films in the program that you’re especially passionate about?

Ngozi Onwurah had made shorts before Welcome II the Terrordome, all incredibly, deeply personal work—she’s such a personal filmmaker. And then to come out of the gate with her feature debut, a dystopian, violent race film in ’90s Britain—that’s punk rock. When I first saw Naked Acts, it became such a favorite of mine—and it still is. Pretty Red Dress too—I’m from South London [where the film is set], so that was always going to resonate. But I think the way that Black masculinity is interrogated in it is so multifaceted. You meet the main character, Travis, when he’s just been released from prison. In a different film, he could just be a generic stereotype, but throughout Pretty Red Dress you discover how he finds confidence within himself, and I think it’s incredibly original. It’s interesting, because I think it’s a film—and I hope I’m not speaking out of turn—that, because of the realities of it being a Black working-class South London story for the most part, maybe doesn’t fit as neatly into what you’d expect from a queer film; and because it is a queer film, it doesn’t fit as neatly into what you’d expect from a Black South London story. It sits at the intersection, and that’s really special, and what makes it so good. Leslie Harris’s Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. is hilarious. It’s really funny, and tragic. It’s rare that you see a teenage girl who is as frustrating and familiar as the lead in that film. Every time I watch it, I think of girls from my school, and I think of myself: the scene in the classroom, where she’s just incredibly defiant, a pain in the arse. That’s me! That was me!

Representation matters!

Exactly! And feeling exhausted by your family not understanding that, actually, they don’t need to be concerned about this because you’re onto different things, and being the first in your family, maybe, to have that ambition. There’s just so much in it. I understand that the film was in part made for educational purposes [the idea for the film was generated from a short film Harris made for Planned Parenthood called Another Girl], but there’s a lot more to it, and I think it speaks to the honesty of the filmmakers.

And I know that you’re a big fan of Jessie Maple’s Will.

Jessie Maple is a rock star, Will is a wonderful film, and I feel incredibly privileged to have screened it in the UK and included it in this program. Maple was a union woman, an activist, and a trailblazer in the true sense of the word. I don’t want that to be forgotten. Film was a medium for her, but I don’t believe she was interested in being an auteur. She was interested in people, and the ways that she could connect with them and improve their lives, including being a news camerawoman and shooting the news in a way that she felt was more fair to the people being reported on. I think there was something about Jessie Maple—and I say this without knowing her, just based on what I know of her, in speaking with Danielle [Butler, Maple’s memoirist]—she was a filmmaker who didn’t have ego. In a way, she was a vessel. That’s something that more of us can embrace.

More: Interviews

Near and Far: A Conversation with Dwayne LeBlanc

The director of Civic and Now, Hear Me Good talks about how his experience as a first-generation Caribbean American and his love of Chantal Akerman’s short La chambre have influenced his work.

The Other Side of Apocalypse: A Conversation on We Were the Scenery

In this Sundance-award-winning exploration of war and memory, writer Cathy Linh Che shines a spotlight on her parents, who were Vietnamese refugees living in the Philippines when they were cast as extras in Apocalypse Now.

The Banality of Apartheid: A Conversation with Milisuthando Bongela

In her intensely personal debut feature, the filmmaker and poet investigates the myths that have shaped South African history through a mix of archival footage, poetic remembrances, and conversations with friends and family.

“A Fragile Film Utopia”: Talking with Ehsan Khoshbakht

The director of the documentary Celluloid Underground discusses his life as a curator, Iranian film culture, and the inherent ephemerality of cinema.