Kanal

There was also, let it not be forgotten, a Polish New Wave, even if not so labeled. One of its big billows for our imagination to surf on was Andrzej Wajda’s Kanal, made in 1956 and released in 1957. It was the centerpiece of the so-called war trilogy, though not too much need be made of that. Almost half a century later, the film is still self-sufficient and unique: an antiwar movie in which we see scarcely a single combat death. But the dark radiance of doom haloes one and all. Most films are about the unexpected; Kanal blends it with the inevitable.

It is September 1944, the fifty-sixth day of the fateful Warsaw Uprising against the Nazi occupiers. The citizens of Warsaw had begun their rebellion on August 1, and for sixty-three days this Home Army fought valiantly in deadly street combat, hoping that the Russians, by now on the other bank of the Vistula, would come to their aid. Polish bravery is proverbial, but so too, alas, is Polish foolhardiness, whose master image is the cavalry charge of Polish uhlans against German tanks. The Soviets, however, with their anti-Polish agenda—they would have just as gladly annexed all of Poland—were perfectly happy to let as many Poles as possible perish, and even shot down some Western planes carrying desperately needed supplies for the rebels. Such aid, though urged by Churchill, was further curtailed by Roosevelt upon pressure from Stalin. It is against this background that Wajda’s film unfurls.

It begins with a masterly four-minute tracking shot introducing us to a company that, the narrator tells us, three days before numbered seventy, now only forty-three—soon even fewer. The camera catches the principals as they crop up hugging walls and ducking constant enemy fire. Most have noms de guerre that mean something: the humane commanding lieutenant, Zadra (roughly, a vexatious person); his rigorous aide, Madry (Wise); the pretty crop-haired Madonna of a messenger girl, Halinka, no last name. The narrator says she “promised her mother on leaving home to keep warm. They probably all made similar promises. All mothers are the same.” These words convey much of the film’s ambiguous tone: there is something funny and touching about these promises, sweet and melancholy about maternal sameness.

Next come the officious sergeant-major and company record-keeper Kula (Bullet), and the handsome officer-cadet Korab (an archaic word for a ship), followed by his tall, blond aide, Corporal Smukly (Slim), who dreams of someday building airplanes. Lastly, a strange unarmed and unconcerned civilian, with a long face and staring eyes: Michal, a composer who just attached himself to the group. “These,” we hear, “are the heroes of the tragedy. Watch them closely, for these are the last hours of their lives.” So no real suspense, just their—and our—hope against hope.

A departing fellow officer tells Zadra, “They won’t take us alive,” which Zadra calls “the Polish way.” Poles are famous for their hopeless heroism; in a subsequent film, Lotna, Wajda was to celebrate their mythic cavalry charge against German tanks. Now the company mingles with a bunch of wounded, including a girl on a stretcher who once sold Smukly his boots. He asks what her mother said about joining up. After a slight pause—there are many pauses of various sizes in this film—she replies, “She’s dead.” Asked about her wound, the girl says, “It’s nothing.” As they carry her away, the blanket slips from her, revealing a leg amputated above the knee.

Zadra’s unit takes overnight refuge in a well-appointed but semiruinous bourgeois house (“Appalling!” the composer calls its luxury), featuring a Bechstein grand on which he starts to play Chopin’s “Revolutionary Étude” before reluctantly switching to a popular tango requested by Madry. Later he improvises; the score by Jan Krenz acquires, as the film progresses, a spooky quality, as of spirit voices groaning. Next morning, Korab chances on Madry and Halinka in bed together. To Korab’s “Hardly the time,” Madry responds with, “Now’s precisely the time for it.”

The composer, with some difficulty, gets through to his wife and small daughter on an army phone line. Just as he receives some reassurance from them, their voices go dead; the Germans have seized them. Even so, the stay in the house is not all bad: Michal gets to leaf through a volume of Botticelli reproductions; Korab finds water and a mirror for a shave. There he is suddenly joined by Stokrotka (Daisy), a blonde good-time girl sweet on him, who claims to be back from safety to be his messenger. The scene is artfully and erotically shot by Wajda, images and words imparting an ironic mixture of insulting insinuations and precipitous love play, cut off suddenly by a close explosion.

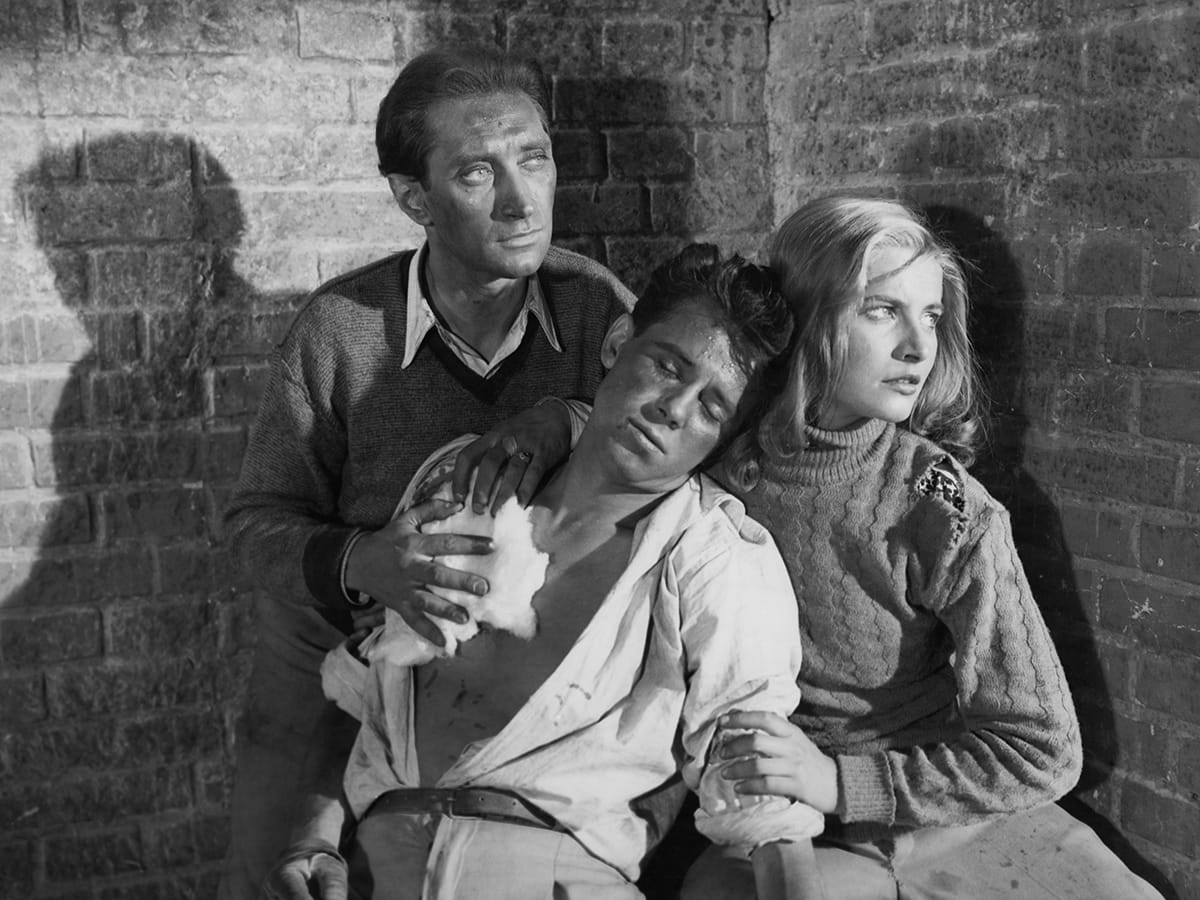

This purgatorial interlude is over; now hell begins. At first it is aboveground, with Korab performing a heroic attack on a tank—one of several sinisterly approaching—successful but leaving him wounded. Zadra grudgingly permits the sturdy Stokrotka to be Korab’s support, as what has been reduced to a mere platoon of twenty-six descends into the sewers, through them to reach its next destination, the city center.

Obviously, we understand this as a descent into hell, even without the composer’s quoting appropriate passages from Dante. Altogether, this pied-piperish musician, playing an appropriated ocarina, his demented eyes bulging from shadowy sockets, is the one wrong note running through the film. Enough that the soldiers are now waist-deep in sewage, submerged in a darkness their flashlights barely alleviate; that diverging sewage canals make them lose their way; that they inadvertently splinter into small groups deprived of contact with one another; and that the movie, without being a smellie, lets you sniff the stench.

Two diversely tragic love stories ensue: Korab and Stokrotka’s and Madry and Halinka’s. And also a sort of third: Zadra’s no less shattering love for his troops. There is a cruel, indeed satanic, irony in what follows, which it is not for me to divulge. Even the carefully preserved company records, kept by the frantic Kula, contribute, in the film’s bitterly sardonic concluding shot, a horrible, symbolic joke.

But everything that happens in these flooded, reeking, tentacular corridors is something devils would laugh at while the rest of us shudder. Jerzy Lipman’s expressionist cinematography, wresting a less than realistic chiaroscuro from an infernal pitch darkness, searingly combines the visions of Piranesi and Georges de la Tour. Grotesque absurdity and hideous frustration enmesh the luckless men and women, their very ears assaulted by ghostly sounds spawned on ghastly silences.

Is Kanal, then, all gloom and doom? Not entirely. There is brilliant shot-making, capturing near-superhuman endurance, magisterially enacted profligate heroism to light up the dark—if perhaps no more so than the matches desperately struck by the groping soldiers. Yet how much that little can signify.