“What the heck is that Pee‑wee Herman?” It was the question on the lips of every 1980s uncle. And they weren’t wrong to ask.

Is Pee‑wee a man or a boy? Does he live in our world or somewhere else? Is he sexual or asexual? Gay or straight? Camp or sincere? Funny or scary? An artifact of the past, or something avant-garde?

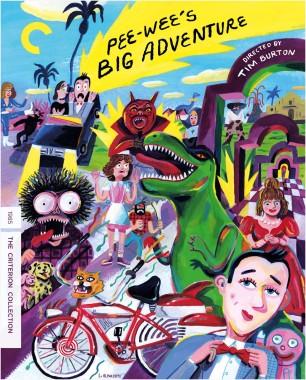

Pee‑wee’s Big Adventure (1985) answers all those questions with . . . yes. It’s an incredible accomplishment: in characterization, by Paul Reubens; and in filmmaking, by Tim Burton, who, in his first feature, balances the unanswerable questions and creates an on-screen world to match the mad genius Reubens had imbued Pee‑wee with onstage.

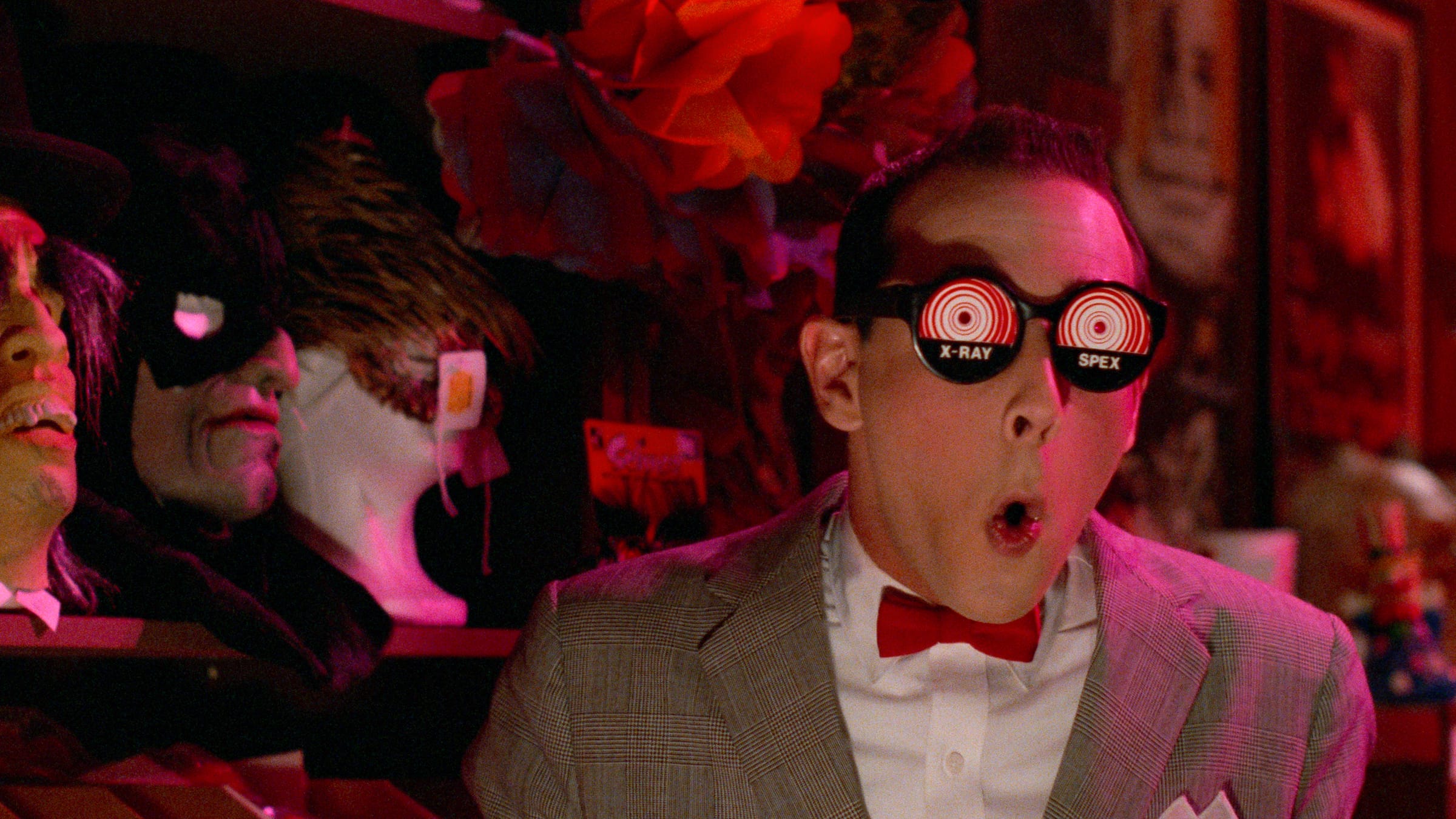

Reubens studied theater at CalArts in Southern California in the early 1970s; he was queer in his life and his sensibility, intense, and committed to the avant-garde. He developed Pee‑wee as part of the new Los Angeles comedy troupe the Groundlings—initially as a nerdy, distracted, failing stand-up comic. Pee‑wee always wore a glen plaid suit with a child’s red bow tie and usually forgot his punch lines. His straight-arrow look was queered by lipstick, rouge, and a Little Rascals haircut. He laughed loudly at his own half-jokes. He was impulsively aggressive but also surprisingly shy. And almost as soon as Reubens created him onstage, he brought him into the real (show-business) world.

Pee‑wee appeared three times on The Dating Game, an indelible enactment of seventies camp. As a bachelor, he was something else entirely from the show’s usual hunky pool boys. The meta-joke was that the bachelorettes couldn’t see how strange he was, but the meta-meta-joke was that the bachelorettes couldn’t see how queer he was.

Next was a stage show. Pee‑wee was inspired in part by Pinky Lee, a 1950s children’s TV host with a similar sense of manic wonder, and his new milieu reflected those roots. In 1981, the star moved into his original Playhouse, on the Groundlings’ stage (it later moved to a rock club). The Pee‑wee Herman Show was populated by Groundlings as slightly sick versions of shiny midcentury kids’ icons like Doris Day and Popeye the Sailor. Pee‑wee lived on the line between childhood and adulthood, with a child’s sense of play and curiosity in an adult world, but also a child’s frustration at his own lack of agency.

The template was set. Other than the stage show’s comparative explicitness about Pee‑wee’s uncanny sexuality—profoundly horny, he was always looking up skirts—the character was as he would appear in film and on television. A boy-man. A little devious, a little angry, but also charming and joyful. A participant in a reality that is recognizable to us but hazy, like a half-remembered childhood.

The show was something of a hipster success, most popular with the kind of New Wavers who were in early on the B-52s and stuck with Grace Jones after disco crashed. Reubens brought Pee‑wee to a national audience on Late Night with David Letterman, where he was a clear favorite of Dave’s, then toured the country as him, with triumphant shows at Carnegie Hall in New York and the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles, and ended up with a movie deal.

Reubens later said the film was conceived as a tribute to Pollyanna, a movie with the sort of corny sweetness that he both loved and laughed at. Working on the Warner Bros. lot, Reubens and his cowriters, Michael Varhol and Groundling Phil Hartman, couldn’t quite crack the script. Noting that people got around the lot by bicycle or golf cart, Reubens asked the studio for a bike and received a gorgeous Schwinn. That’s how the project became a picaresque version of Bicycle Thieves: a love-story road movie about film, Americanness, and a very, very cool bicycle. Pee‑wee retains some Pollyannaish innocence and spreads some Pollyannaish goodwill as he travels a country populated by vestiges of postwar iconography: bikers, greasers, cowboys, a con on the run in a fifties convertible. The grand finale takes him to the Warners lot itself, turning both Santa’s North Pole and Godzilla’s Tokyo upside down as he’s chased through genre-film sets.

For their ninety-minute film, the writers knocked out ninety pages of script, just like showbiz insiders say to do. It is a monumentally strange movie that is framed in a classical way, with Pee‑wee waking up in a suburban idyll, adoring his love interest (the bike), encountering the villain (“FRANCIS!,” his spoiled neighbor, who covets the bike), then hitting the road to find his love again. After they are finally reunited, he realizes that, as important as his bike is, the real love was the people he met along the way (only sort of including his actual human love, Dottie, whom he treats the way a closeted teenage boy treats his best female friend in high school).

The studio issued Reubens a director, but in a somewhat naive flex, he rejected their choice. Given a week to choose a pro to be in charge of his magnum opus, he thought of a fellow CalArts alumnus he’d heard about named Tim Burton. Reubens screened Burton’s Frankenweenie and knew he had his man. Burton had made the live-action short, about a boy who tries to bring his dead dog back to life, in 1984, while employed as an animator at Disney. Frankenweenie and his 1982 stop-motion short, Vincent—about a boy’s obsession with Burton’s own childhood hero, actor Vincent Price—were getting the twenty-six-year-old director talked about in certain circles as a wunderkind. Reubens was obsessed with Frankenweenie’s German-expressionism-inspired aesthetic, and it was clear Burton had thought a lot about it too. Here was a guy who got it, who could make Pee‑wee’s world as beautiful on-screen as it was in Reubens’s mind.

Watch Frankenweenie and Big Adventure together, and you can see what clicked for Reubens. Frankenweenie shares with Burton’s later work a fascination with the macabre, but it also has a lot in common with Pee‑wee’s vibrant world. Each film centers an alienated American child who experiences both thrilling freedom and the cruel, unpredictable dominion of adults. Both offer the viewer an experience that comes partly from what’s directly represented on-screen and partly from their allusion to the sort of cloudy, mythic images that impress themselves upon us in childhood, the feeling of struggling to make sense of something that is exciting and unsettling at the same time. Frankenweenie is beautiful; it is also both funny and genuinely scary. It concludes in a miniature-golf windmill, exactly the sort of hyperreal landmark that dots Big Adventure. It is a story about a storyteller—the boy is a filmmaker—and like Big Adventure, it’s a story that lives in the world of stories.

Burton’s next feature would be Beetlejuice (1988), a supernatural comedy that lives similarly between the practical and the imagined, as its characters lose their agency in the “real” world and are forced to contend with a spirit world that is both terrifyingly dreamlike and maddeningly mundane. His spoof Mars Attacks! (1996) careens through vintage sci-fi as anarchically as Pee‑wee careens through the Warner Bros. sets and, despite being broadly comic, retains a feeling of menace. Even 1994’s Ed Wood, on one level a relatively straightforward biopic, uses its black-and-white aesthetics to place itself squarely in the heightened reality of film and the imagination, and features a Pee‑wee-like naif desperately trying to create images reflective of his deepest depths.

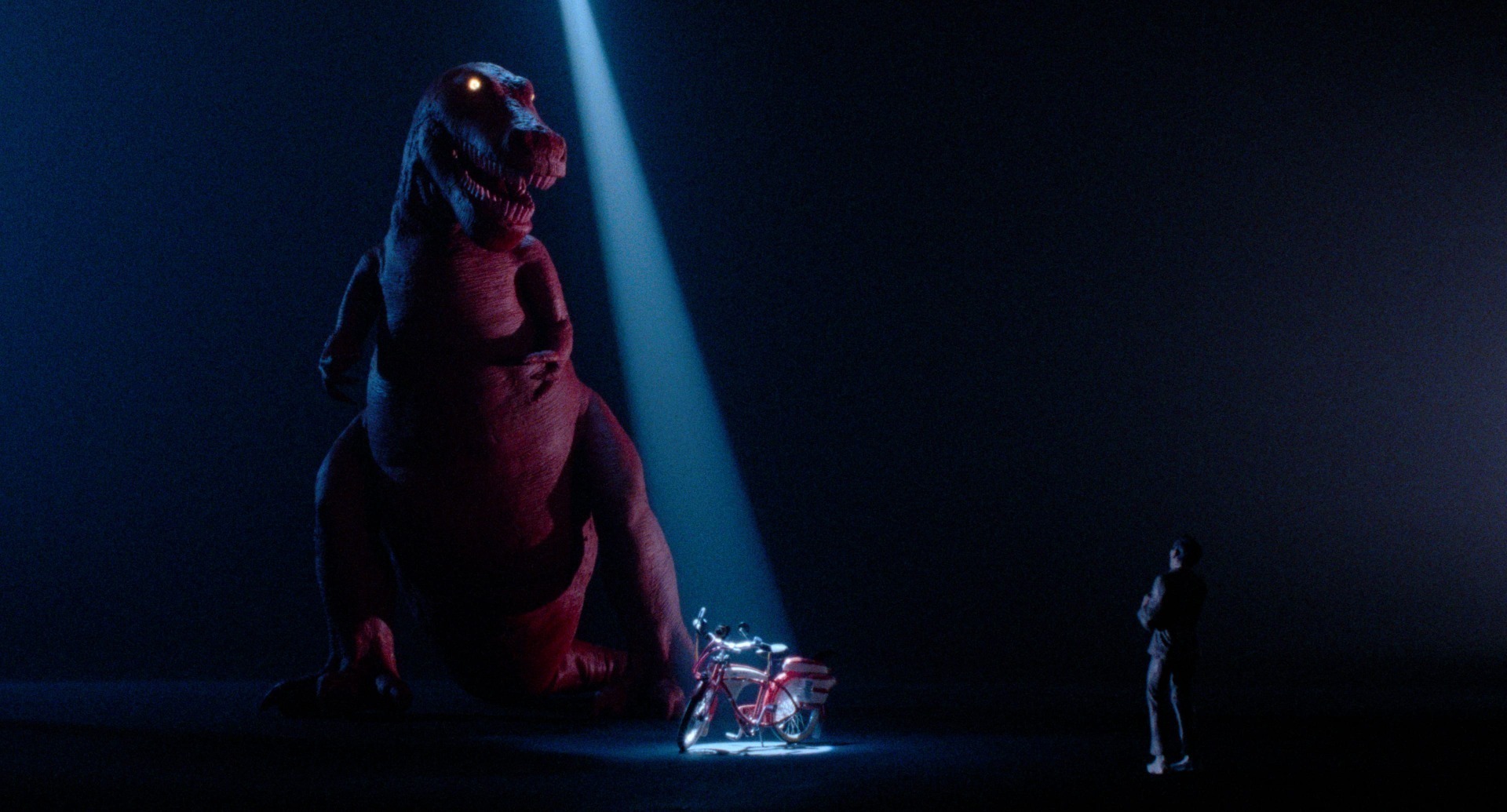

Big Adventure is more concerned with getting laughs than much of Burton’s oeuvre, but it also wrestles with the dark side of childhood. There’s plenty of unbridled joy: Pee‑wee’s gadgets and gizmos. The freedom of the open road. A ridiculous dance that earns Pee‑wee a motorcycle. But in addition to the central terror—the loss of the treasured bike—the film is filled with scary clowns and hungry dinosaurs and grown-ups (like the cops and the Alamo tour guide) who are contemptuous of Pee‑wee’s feelings.

The two came together almost by chance, but the match between Burton’s and Reubens’s sensibilities is near perfect. Their central filmmaking challenge was how to make Pee‑wee’s strange, liminal world feel some cinematic version of “real,” so that the madness added up to more than just madness. In his appearances on other people’s TV shows, Reubens was always at play in someone else’s reality, his weirdness contrasted with the host’s bemusement. The Pee‑wee Herman Show was conscribed by three theater walls and a proscenium. What would Pee‑wee become in the limitless universe of film?

My own most vivid memory in a movie theater is of the opening of Big Adventure. My mom took me—I was six. Pee‑wee’s bunny slippers coming to life and sniffing at a stuffed carrot. The Rube Goldberg device that powers his breakfast. The aquarium outside his bathroom window. And, of course, his bike. It’s hard to imagine another director, even given the gift of Reubens’s vision, creating something so extraordinary.

Burton shoots this mad vibrancy soberly. He had storyboarded throughout, in large part to show Warners he was a responsible adult. We see plainly the least plain things imaginable: every corner of the screen is crammed with aesthetic invention. While the dream sequences are more heavily stylized, Burton plays the wildness of the waking scenes straight. He shows us things as we might perceive them in our mind’s eye, half-recalling an old movie. Shadowy and slightly noirish as Pee‑wee stumbles through back alleys. Sunlit and cheerful as he walks down a suburban street. Wide-open and spare in framing the Alamo. And all of this is bound together by Danny Elfman’s whirling score, his first of many collaborations with Burton.

The visual approach mirrors the narrative one. Pee‑wee bends the world to his will—he queers it. As outlandish as his appearance and demeanor may seem, he is not incongruous with his environment, where the fantastic is quotidian and things are chaotic but not out of control. When Pee‑wee is thrown into a rodeo, the stakes of the bull-riding (and the bull) are very real, even if Pee‑wee is dressed like a singing cowboy’s fever dream. When he meets the romantically minded waitress Simone, she feels like someone who really works in a diner, even though her melodrama comes straight from a Hollywood weeper and her boyfriend looks like Bluto.

The element of Big Adventure that is most unmistakably Burton’s is the stop-motion animation. There is no more iconic moment in the movie than the ghost trucker Large Marge’s explosion into a stop-motion horror show, and no image more striking than Pee‑wee’s nightmare of a roadside-attraction dinosaur brought to terrifying life by animation. Burton has described stop-motion—which makes conspicuous the hand of the creator—as “more real than real.” The movie’s dream sequences, in which horror-film clown doctors and the aforementioned dinosaur destroy Pee‑wee’s beloved bike as he looks on, helpless, vivify a theme that Burton has returned to many times, another of his affinities with Reubens: that childhood, while intoxicating, also makes us feel trapped. As in a dream, we can’t save the bike from the dinosaur’s jaws.

Stop-motion is uniquely suited to expressing the uncanny, as it is both entirely artificial and entirely human, and Burton, whose work is so closely associated with the uncanny, has continued to use it brilliantly. The show-your-work element of the form lends heart and warmth to even the strangest moments in Beetlejuice or 1993’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, conceived of by Burton and directed by his fellow animator Henry Selick. The scariest things are funny, and the opposite is often true as well.

Like roadside Americana, Hollywood is a version of hyperreality that exists in our world as well as in Pee‑wee’s. So it makes sense that Big Adventure’s exciting finale should have Pee‑wee chased by security guards through those studio sets. It’s easy to presume that the script called for the beach-party set, and that Burton threw in Godzilla (he was, and is, obsessed). And it’s impossible to imagine that anyone but Reubens suggested he dress like the Flying Nun. It’s one of the most delightful sequences in cinema—there are few better arguments for the sheer joy of the movies.

It’s worth noting that it’s also a false climax. Because Pee‑wee gets away from the studio, having liberated his bike from the set of the film it was being used on, and runs straight into a full-on existential dilemma. He has his bike, but a pet store is on fire. He is forced to choose between his own greatest dream (to play, forever) and the deepest responsibility (life and death). And he chooses responsibility. He drops his bike on the sidewalk and runs in to save the animals. It is a triumph not just over danger but over his own childish selfishness. And when the cops grab him (and his bike), he seems to have lost it all.

Ultimately, though, he is saved by his own Pee‑wee-ness. Showbiz sees how special he is and trades him his bike and his freedom for his life story, and he gladly accepts the deal. Because what is he if not a charming egotist? The power of film, even hokey film, combined with the magic of Pee‑wee, brings everyone together at that ultimate American venue, the drive-in.

Big Adventure took Pee‑wee Herman from cult hero to pop-culture icon, and Tim Burton from promising art-school grad to bankable director. Critics were largely baffled by the movie, but audiences immediately got the joke. It made more than five times its budget in theaters, and that success gave Burton the opportunity to make the perhaps even stranger (and certainly more profitable) Beetlejuice, and then the deeply personal (and even more successful) Edward Scissorhands (1990). Burton’s films have become a genre unto themselves: beautiful, fantastical, gothic dreams that are always fun and funny besides. Art films that regular folks have bought tickets to by the millions.

Pee‑wee would have many smaller adventures. Big Top Pee‑wee (1988) is delightful but never reaches the heights of its predecessor. Pee‑wee’s Playhouse (1986–91), a network children’s show with a queer, arty sensibility never seen before or matched since, changed many kids’ lives (mine included). Even Pee‑wee’s final outings, the 2010 stage revival of The Pee‑wee Herman Show and the 2016 movie Pee‑wee’s Big Holiday, are absolutely worth your time.

In the end, though, there is one Pee‑wee magnum opus. A combination of a great filmmaker’s unique way of seeing and a genius writer and performer’s special gift. A film that made a generation of weirdos see ourselves and the world in all kinds of in-between ways. They took a picture. It’ll last a long, long time.

More: Essays

The Man Who Wasn’t There: The Barber of Santa Rosa

For this existential noir, Joel and Ethan Coen drew inspiration from crime-fiction master James M. Cain’s lean, hard-boiled style and interest in the quotidian world of work.

Network: Back to the Future

Centered on the emotional unraveling of a failed newsman, this darkly prescient satire envisions the collapse of American society as we knew it through an unsparing critique of corporate media and capital accumulation.

Birth: Love Eternal

Jonathan Glazer’s enigmatic second feature explores the terrors of being desperate for love—and the vulnerability, loneliness, and difficulty in understanding other people that might drive this state.

Kiss of the Spider Woman: Revolutionary Transgressions

A resounding critical and popular success upon its release, Héctor Babenco’s adaptation of a literary masterpiece by Manuel Puig was an unprecedented cinematic fusion of a radical politics of sex with a sexual politics of revolution.