In the penultimate scene of House Party (1990), on the night of his friend Play’s big shindig, Kid walks out of a holding cell packed with Black men. The desk sergeant remains mute while Kid silently inspects his belongings to ensure that the corrupt cops haven’t stolen his most sacred possession—the Afro pick he uses to maintain the architectural integrity of his high-top fade. When he finds his friends waiting for him in the police precinct’s lobby, neither they nor Kid utters a word.

Here as elsewhere, writer-director Reginald Hudlin’s feature-film debut—also that of leads Christopher “Kid” Reid and Christopher “Play” Martin—does not overly concern itself with informing the audience. It may seem antithetical, but this lack of unnecessary minutiae actually makes the film more realistic. While a simple, quick-witted quip from Kid in this penultimate scene might have served as a subversive critique of the criminal justice system, such a scripted piece of performative social commentary was unnecessary. House Party’s core audience didn’t need dialogue from the desk sergeant to know what Kid has been charged with. There is a reason why Hudlin did not waste time scripting words for Kid or his motley crew of compadres upon his release from police custody:

House Party is a documentary.

While the nation’s most iconic works of visual art authentically document an element of this country’s cultural ethos, they are often fictional. The Founding Fathers’ big house party memorialized in John Trumbull’s famous oil-on-canvas Declaration of Independence never actually occurred. The stern-faced farming husband and wife who look like they invented green-bean casserole in American Gothic were actually a dentist and an art teacher. Not only were these models not a married couple, but painter Grant Wood said he chose them because they looked like “the kind of people I fancied should live in that house.” Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 portrait of George Washington, posed like Captain Morgan while crossing the Delaware with an American flag, is as accurate as a painting of blond-haired, blue-eyed Jesus. Unlike House Party, the idyllic Americas depicted in such creative masterpieces share one common element:

Black people do not exist.

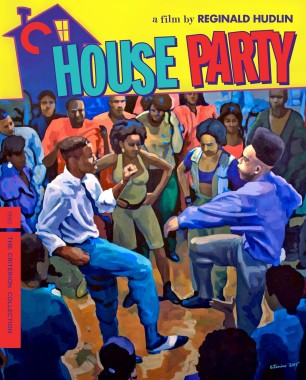

House Party, conversely, manages to paint a more perfect picture without sacrificing authenticity for romanticized mythology. Based on the short film that served as Hudlin’s Harvard senior thesis, the film is set in a quintessentially American, authentically Black community filled with fully realized people who exist not as spectacle but as reality. Moreover, for the people whose lives, liberty, and pursuit of happiness were documented on-screen, this classic proved just as iconic as George Washington’s windswept, star-spangled banner or the figures who became avatars for the spirit of rugged individualism by cosplaying pastoral peasants.

Before rap music emerged as the most influential and financially lucrative genre on the planet, the billion-dollar corporations that controlled the mainstream media doubted that a movie centered on hip-hop could even turn a profit. In pre–House Party Hollywood, “Black movie” was synonymous with “limited appeal.” The few “urban” movies that did receive a green light were given low budgets. Back then, the new niche culture was considered so dangerous that some moviegoers had to watch House Party in fully lit theaters because some venues refused to dim the lights. (To be fair, in the 1980s, behavioral psychologists believed dimmer switches were the only thing preventing Black teenagers from bursting into random acts of thuggery.) By the end of its first week in theaters, Hudlin’s film had earned double New Line Cinema’s paltry $2.5 million investment, audiences across the country had fallen in love with House Party, and Hollywood suddenly realized that Black movies . . .

Okay, Hollywood hasn’t changed much, but still.

Like most great works of art, Hudlin’s not-so-still life is simultaneously original and familiar. Informed by his upbringing in East St. Louis, Illinois—one of many Black Americas once invisible in classic Hollywood cinema—the film’s people and places might be fictional, but they represent something recognizable and three-dimensional. When Play mentions that his parents went “down south” to visit South Carolina, real people with real histories can infer that Play is likely descended from formerly enslaved people who migrated to the area where this film takes place. Still, the film never explicitly reveals its geographic setting. There’s no on-screen caption announcing a city, no shot of a skyline to anchor the narrative in a specific place. And yet, for anyone with a discerning eye, the location is unmistakable. The story takes place in an overpoliced neighborhood where white law enforcement officers are known for harassing residents. In 1990, the year House Party was released, Black men were three times more likely than white men to be killed by law enforcement. Over thirty years later, the ratio remains the same: three to one. But House Party is not just a story about policing. It’s also a portrait of a community where the schools and jails reflect the same demographics, where a high-school cafeteria is just as Black as a cellblock. In 1990, two-thirds of Black students attended predominantly minority schools. Today, that number has increased to 84 percent.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the film is its portrayal of socioeconomic fluidity within Black neighborhoods. House Party is not set in a mythical African American locale where well-meaning white saviors, played by Michelle Pfeiffer or Sandra Bullock, swoop in to rescue preternaturally gifted but “troubled” Black youth from becoming gangbangers and teenage mothers. Instead, the film’s characters live in a real place, where entrepreneurs live next door to garbagemen, and where teachers share streets with short-order cooks. The trope of “the hood” as a prison from which only the most successful Black people can escape exists solely in the white imagination. In reality, Black children feel less safe in white neighborhoods. For them, messianic figures or tired tropes are less important than gathering with a few friends trying to dance, flirt, and avoid their parents for a night. There’s only one place where someone like Kid’s love interest, Sidney (Tisha Campbell), the middle-class daughter of a successful entrepreneur, can walk to visit her friend Sharane (AJ Johnson), who lives in the housing projects a few blocks away:

A place called “Black America.”

No character embodies this reality better than Kid’s father, Pop, played brilliantly by the late Robin Harris. In one of his final performances before his untimely death, Harris brings to life a man who is equal parts hilarious, exasperated, and real. For anyone raised to appreciate the poetic brilliance of Dolemite or the gospel of Black fatherhood, a man whose only mission is to give his son a better life is instantly recognizable. Pop is not wealthy. His job title is never revealed. And yet everyone who has ever been told to keep their mind “on them books and off them gals” knows the people for whom Pop works:

Them white folks.

But Pop is more than comic relief. He is the moral compass of the film, the last vestige of authority in a world temporarily liberated by youthful exuberance and music. He doesn’t hover like a helicopter parent or deliver long monologues imparting life lessons. He simply enforces the rules of the Black cinematic universe that every Black child knows instinctively. Sidney doesn’t need a long explanation when Kid says he’s “on punishment.” She understands that Pop is no different from the parents she had to bamboozle to attend Play’s bash.

That’s why the music stops and the kids collectively snap back to reality when a Black father shows up at Play’s party. In a parent-free, quasi-fictional world without visible teachers, truant officers, or PTA meetings, Pop is the last line of defense between community and chaos. He commands respect not because he demands it, but because he embodies the rules these kids have been raised to respect.

Being a Black protagonist in classical Hollywood cinema often comes with the burden of proving one’s social value or displaying unimpeachable moral integrity. But because House Party is unencumbered by the blinding light of the white gaze, the audience doesn’t need to know if Kid is a straight-A student or how often he attends church. In the world where House Party takes place, Kid is allowed to be a flawed, imperfect, fully human teenager—worthy of redemption and the audience’s grace—simply because he’s seen as what he is: a human being.

While Stab and his crew (played by members of the legendary music group Full Force) might appear to be the film’s antagonists, they’re less villains than distorted, inverted reflections of Kid, Play, and their friend Bilal (Martin Lawrence). Stab (the Legend Paul Anthony) uses brute force as easily as Play weaponizes his charisma. Zilla (B-Fine), like Kid, is the awkward, less charming sidekick. Pee-Wee (Bowlegged Lou), high-pitched and unpredictable, is similar to Bilal. Stab and his crew are not evil; they’re familiar. And like everyone else in this patchwork quilt of a neighborhood, they belong. They are part of the same fragile ecosystem held together by community and proximity.

The true antagonist of House Party is America.

If House Party takes place in a Black America governed by rules, respect, and community, then America is its adversary. It makes more mischief than the mischief-makers and outbullies the bullies. It is an invader of safe spaces whose allegations are not worthy of being articulated. America does not protect Black communities or serve its residents; it enforces. It is the unseen force whose agents disrespect the people who most deserve dignity. America is the opposite of Black joy.

But House Party is not a story about defeat or the America that devours. It was one of the first films to center hip-hop as part of Black American culture. But it’s not about the genre or “the urban experience”; instead, it is a celebration. It is a movie about Black people who live in a Black community with nerds and aspiring college students and bullies and concerned fathers and rapscallions and Kool-Aid makers and DIY disc jockeys and nosy neighbors and all the sweet and bitter joy and pain and shared knowledge that inspired the ancient African American idiom:

“What’s understood don’t need to be said.”

Somewhere, tonight, a group of young, unextraordinary Black people will seek the safety of a space where this country’s tentacles cannot reach. Perhaps at a cookout or frat party or behind a bedroom door at their cousin’s house. Invariably, someone will perform the same iconic dance routine from House Party. Although they will do the same shuffle and kicks, it is likely that they have never actually seen the film where Reginald Hudlin captured this uniquely Black slice of Americana. Yet, somehow, they understand.

In the penultimate scene of House Party, Kid walks out of a cell packed with Black men. Undaunted by his narrow escape, the teenage embodiment of America’s multiracial coalition turns to find his community awaiting his release. His charismatic, loyal friend Play—whose South Carolinian ancestors’ uprisings, protests, and movements forced America to become a democracy—rises first. Kid’s new sweetheart, whose parents do not work for “them white folks,” stands next. So does the around-the-way girl. Finally, the buddy who has no idea that his basement hobby is about to change the musical universe rises to his feet, finishing the portrait of “the kind of people who live in this house.”

This, too, is an American masterpiece.

More: Essays

The Man Who Wasn’t There: The Barber of Santa Rosa

For this existential noir, Joel and Ethan Coen drew inspiration from crime-fiction master James M. Cain’s lean, hard-boiled style and interest in the quotidian world of work.

Network: Back to the Future

Centered on the emotional unraveling of a failed newsman, this darkly prescient satire envisions the collapse of American society as we knew it through an unsparing critique of corporate media and capital accumulation.

Birth: Love Eternal

Jonathan Glazer’s enigmatic second feature explores the terrors of being desperate for love—and the vulnerability, loneliness, and difficulty in understanding other people that might drive this state.

Kiss of the Spider Woman: Revolutionary Transgressions

A resounding critical and popular success upon its release, Héctor Babenco’s adaptation of a literary masterpiece by Manuel Puig was an unprecedented cinematic fusion of a radical politics of sex with a sexual politics of revolution.