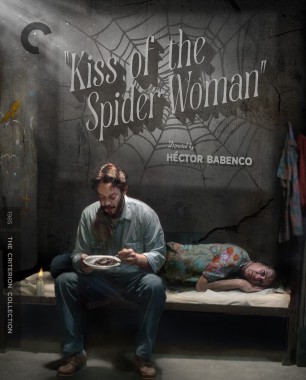

Kiss of the Spider Woman: Revolutionary Transgressions

Film restorations are frequently aimed at reviving the career of an actor or director. The restoration of Héctor Babenco’s Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985) is a different case; it revives not merely individuals but an entire universe that has been too long forgotten, one characterized by sexual boldness, political bravery, and aesthetic invention. It brings together the intoxication of a new style in Latin American literature; the revival of a popular Latin American cinema enabled by the return of democracy to much of the region following an era defined by coups; and the power of mixing North-South influences into the best kind of hybrid. Its rerelease into the world now pops the cork on a fizzy cinephilia bottled up for far too long.

Manuel Puig had been turning down offers to film his wildly original novel Kiss of the Spider Woman for nearly a decade. One of the stars of the Latin American Boom—the sixties and seventies movement that remixed the codes of literature, updating realism, pop culture, and narrative strategies—Puig was a lifelong cinephile. He had haunted movie theaters with his mother in his native Argentina, submerging his own gay desires in fantasies of the silver screen from an early age. All grown up, he enrolled in Rome’s legendary Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia (founded by Benito Mussolini’s government in 1935), where a generation of Latin American filmmakers, including Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Fernando Birri, studied. In the end, although he turned to literature instead of cinema, his novels always gestured to the movies; it’s no coincidence, then, that Spider Woman is centered on fantastical films conjured inside a prison cell to free the spirits within. Henceforth, Puig would make his films with words.

Puig’s novel is set in Buenos Aires in 1975, after both Puig and the Argentine-born Babenco had left the country; the period was one of growing government repression and political unrest. It was published in 1976, the year that Argentina’s government was taken over by a military junta that initiated years of dictatorship, brutal restrictions, and the disappearance of around thirty thousand Argentines. It provides, as Uruguayan novelist Caro De Robertis has put it, “a deeply incisive rendering of the mechanics of surveillance and repression” that would grip the country until 1983. (And the region: Latin America was engulfed, dominated by dictatorships and military coups that stayed in power in Brazil and Uruguay, for example, until 1985, and in Chile until 1990.)