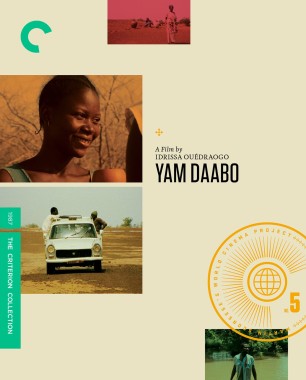

Yam daabo: On Idrissa Ouédraogo’s Humanist Cinema

Yam daabo (The Choice, 1987) opens on two men working over a mud firepit. Tight close-ups show only their limbs—an arm stoking pieces of charcoal, hands vigorously pumping a dual-air-drum mechanism to intensify the flames. The hearth and fire are central metaphors for life in this Mooré-language film by Burkinabe filmmaker Idrissa Ouédraogo, about a family uprooting themselves from a drought-stricken village of the Sahel to find new possibilities and paths in another region.

In this precredit sequence, before the family departs, a crowd of villagers with empty baskets watches and waits, in a silence interrupted only by the cries of a baby. Mute crowds of spectators are a recurring motif throughout the film: a communal counter-gazing that responds to, reduplicates, and questions the gaze of the camera itself. Suddenly, on the parched dusty road, a bright-red Mack truck appears in the distance, filled with packaged aid goods labeled “United States of America.” The bodies of the villagers, sitting or standing under the searing sun, are all oriented in the direction of the road. Later, they line up patiently in front of the truck, waiting for the theater of humanitarianism to take place. The framing in this tightly edited opening sequence often isolates body parts—an arm, a leg—in tension with the filmmaker’s embrace in the rest of the film of more humanistic framings, which honor characters’ individualities with medium and close shots of carefully lit faces. Rather than serving as a prelude to the narrative of a family that refuses both international assistance and a rootless existence in the cities, electing instead to look for greener pastures elsewhere, this sequence can be read as its antithesis. Ouédraogo presents us with a compendium of images familiar from the colonialist humanitarian scripts that play out on the televisions of the world, only to deconstruct them during the rest of the film by focusing on the depth and humanity of an ordinary family.

Hardly anyone speaks in these first scenes. As the family journeys away from the village, the sparse dialogue revolves entirely around water and the endless quest for this life-sustaining liquid. “Ali, give me some water” is the film’s first spoken sentence, to which the little boy responds: “There is no more water.” The sounds of empty calabashes resonate, as women walk in a sun-scorched, bare landscape. This is a far cry from the laughs, chatter, and loud voices that fill the air in the new place the family settles in, where there is abundant water and vegetation. Freed from the constant threat to their survival, the narrative plot can finally start, one that centers the emotional turmoil of the family members: budding love, grief, rage, friendship, and jealousy. What is sometimes mischaracterized as a love triangle is, more accurately, a conflict between a pair of lovers and a stalker. Bintou, the family’s adolescent daughter, loves Issa. After she rejects Tiga, her close friend’s brother, he escalates into attempted sexual assault and attempted murder.