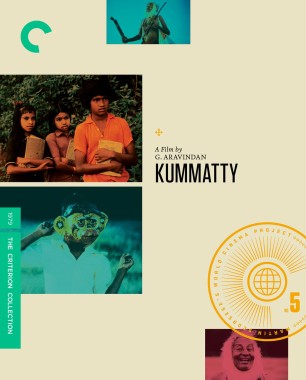

Kummatty: A Children’s Movie for Adults

By Ratik Asokan

A young boy stands on a dusty path, wearing tiny shorts and a bright shirt. He looks up to see a silhouette take shape against the twilight sky. The blur slowly approaches, stumbling from side to side, bells rattling with each step. As the scene comes into focus, an old man is revealed on a grassy plain, in wrinkled pajamas and a ragged tunic, a white postiche hanging off his chin. Trembling, the child steps back, then locks eyes with the apparition as he enters the frame. They stare at each other for a few moments before the boy scampers past, looking backward all the while. “I was frightened,” the boy, Chindan, tells his friends afterward. “Kummatty was so close, he could have touched me.”

This encounter, which comes a third of the way into Kummatty (1979), establishes its titular character’s dual nature. Kummatty, played by the veteran actor and dancer Ambalappuzha Ramunni, is both a sprite who belongs to the landscape and a man of flesh and blood. Over the course of the movie, which is told from the perspective of children, he shaves, bathes, and smokes, then performs feats of conjuration and transfiguration. It is his quotidian behavior that makes his miracles compelling. “My film Kummatty is on a real personality, and an assumed one,” G. Aravindan said. “If he is not this, he will remain just as an ideal.”

The director’s treatment of the film’s setting is similarly double-sided. Kummatty was shot on location, in and around a village in Malabar, a region in the state of Kerala, on the southwestern tip of the Indian peninsula, where Malayalam is the dominant language. Most of the cast, both young and old, are locals. Aravindan asked them to play themselves, and go about their lives, which he observed with a painterly eye, at a contemplative rhythm. Two types of compositions dominate: Chindan and his friends are seen from afar, as part of panoramas, or in close-ups, their faces bathed in light. The camera mostly stays still or gently pans, as the children excitedly rush about. In a poignant segment, Chindan runs to call a doctor, racing across a vast prairie with mounting concern, his image receding into the distance. Meanwhile, in the foreground, a man indifferently washes his water buffalo.

It is an elusive film: at once earnest and fantastic, carefree and mindful, imaginatively kindred to a folktale and materially grounded in cinema. The scholar V. K. Cherian characterized it as an exercise in magical realism. Others have described it as a children’s movie for adults.

That ambiguity is typical of his oeuvre. In nearly a dozen features, made in a blaze of creativity between 1974 and 1991, Aravindan persistently blurred the line between reality and myth. Saints, oracles, and visionaries find their way into his stories, which are mostly set in Kerala, whose natural beauty he reverently lingered on. Forests, rivers, and hills take center stage, as if they were characters, while modernity is pushed to the margins, or ignored altogether. Enactments of shastriya kalas and lok kalas, or classical and folk arts, interrupt the narratives, layering them with allusions. Throughout, the gaze is both intense and tranquil, on the cusp of revelation, as in the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, an avowed influence. “I can never expect to be an atheist,” Aravindan once said. “Concretely, I believe in supernatural powers, in the mystical—these phenomena are very real.”

Kummatty may be his most emblematic project. By entering the world of children, and borrowing their license of serious make-believe, he was able to express more directly than elsewhere the spirituality that underlay his vision.

Govindan Aravindan was born in 1935 in Kottayam, a town at the heart of Kerala’s cultural life, where many publishing houses and newspapers are based. He hailed from a family of Nairs, a customarily matrilineal, generally landed community, at the higher end of the caste hierarchy. His father, M. N. Govindan Nair, a barrister, contributed satirical pieces to periodicals; writers frequented their tharavad, or ancestral bungalow. Aravindan was artistically inclined from his schooldays: he drew and painted, learned Carnatic music, sang at social occasions.

In 1954, after graduating from college with a degree in botany, he was hired by the national rubber firm as a field officer, a job that left him with time for creative pursuits. He first tried his hand at cartoons. Cheriya manushyarum valiya lokavum, or Small Men and the Big World, debuted in the venerable weekly Mathrubhumi in 1961. In spare, tender lines, the strip follows the misadventures of Guruji, an idealistic retiree, and Ramu, a college graduate with bourgeois aspirations.

Comic interludes about the middle class, sketched with similar irony, often break into Aravindan’s movies, which otherwise steer clear of social critique. In the latter part of Kummatty, a snow-white puppy (more on this poor creature later) strays away from Chindan’s modest village, where the bare huts are thatched, into a grand tharavad, home to a bourgeois family who wear stiff Western clothes and speak stiffer English. They take in the mutt, make their servant give him a bath, and then summon a vet, who warns them about adopting a “country” animal. “Don’t worry, baby,” the steely patriarch tells his heartbroken daughter. “I will get you a nice Pomeranian pup. Throw this away.”

Cheriya, which ran for thirteen years, was Aravindan’s ticket into Malayali artistic circles. In the late 1960s, he seems to have been everywhere, at one moment singing with the Sopanam music club, at another designing sets for the Navarangam theater company. He was particularly drawn to the shastriya and lok kalas, which younger artists were then revitalizing with the resources of modernism. No one did more for their revival than Kavalam Narayana Panicker, an exponent of Thanathu, or Indigenous, drama, whose early plays Aravindan directed. The playwright repaid the favor, writing several movie scripts, including for Kummatty.

Panicker’s stamp is all over the film, which pays an elaborate homage to Kummattikkali, a traditional dance of Malabar, performed during the Onam festival by men in animal masks and skirts of plaited grass who go from door to door to demand their fair share of the harvest on behalf of Lord Shiva. Panicker gave Kummatty these masks, which he carries in a bag, as well as the swaying choreography, which he exuberantly performs, along with the children, in multiple song-and-dance passages. Their sweet ditty, which Panicker composed, reminds us of the Kummattikkalis’ divine origins:

Kummatty has come to visit the world

Will he come flying? On a palanquin? On foot or seated?

Such is the procession of Kummatty of our fairy tales

The reference is made explicit when professional Kummattikkalis fleetingly pass through the story. They are first seen from up close, donning their costumes, then from a distance, hopping and leaping across the grassland, trailed by delighted children.

Aravindan was thrust into filmmaking by happenstance when the novelist Thikkodiyan approached him with a script. Uttarayanam (1974), which the director said “was shot essentially on instinct,” is a family saga that allegorizes the collapse of nationalist values. The black-and-white mood piece, which now appears dated, borrows much from the neorealism of Satyajit Ray: extended living-room discussions, troubled glimpses of street life, nondiegetic use of Hindustani music, a middle-class antihero. K. Ravindranathan Nair, a cashew exporter and patron of the arts, was so impressed that he funded Aravindan’s next five projects, no strings attached. The filmmaker put this creative freedom to good use in a series of quietly daring experiments, through which his style emerged.

Key elements of Kummatty appear in the two features that preceded it. Kanchana Sita (1977), which retells a late chapter of The Ramayana, can be described as a cinematic pilgrimage. The mythic heroes, Rama and Lakshmana, attend to various ritual errands, in the course of which they walk, for the better part of ninety minutes, across long stretches of the Godavari River Delta. Aravindan keeps their dialogue to a minimum and avoids narrative incident, finding drama in the warmly colored landscape itself.

Kummatty adapts this technique to Malabar. The tone is set in the first scene, which begins with the sun rising behind mountains on the horizon, its crimson glow flooding the dark valley below. Then the camera pans across the hills blanketed in mist. As crickets chirp, birds screech, and a rooster crows itself awake, Panicker is heard singing, in a deep voice, about the origins of the universe: “In the beginning / From the east and from beyond the hills / Deep red like a ripe betel nut . . .” By the time Chindan is seen, brushing his teeth with neem twigs, his surroundings have acquired an inner radiance.

From this point on, the movie largely unfolds outdoors: in the woods, where the children play hide-and-seek; beneath an aged tree where Kummatty sleeps; and, most of all, on an enormous steppe, which characters cross and recross under unrelenting sunlight, crisply framed against the sky. The flat, empty terrain allows Aravindan to adopt a number of perspectives, from the grass-level inspection to the wide-angle vista. When Kummatty leaves the village, he walks away from the camera, which is placed low to the ground, his figure disappearing down a slope as if he is returning to nature.

In Thampu (1978), Aravindan tried his hand at cinema verité. In a manner that recalls the cinema of Jean Rouch, he brought a circus troupe to a remote hamlet, invited its residents to attend the entertainment, filmed their reactions, and placed this footage within a lightly invented story. Without a central protagonist to follow, the camera roams across the stage and the audience, from one anonymous person to another, in a series of brief, oblique character sketches.

This approach is refined in Kummatty, which was also made on the go. The plot, such as it is, turns on Kummatty’s arrival in the village, where he wins over the children, who are initially skeptical, not to say afraid, of him. Their interactions alternate with vignettes of rural life: threshing the harvest, trips to the market, religious festivals. It is generally unclear where fiction ends and documentary begins, except when Aravindan winkingly contrasts them. An amusing episode finds Kummatty splashing about in the village tank by himself. Not two minutes later, grainy footage shows a crowd of women in the same place, washing clothes and bathing their children.

Played by a boy named Ashok Unnikrishnan, who never acted in another movie, Chindan is the only character granted sustained personal screen time. The first ten minutes of the film effectively reprise his daily routine: from the trek to school, where he sits through classes, to the prairie for evening play, then back home. This sequence closes with a double portrait. In the darkness of their unelectrified hut, with a doting younger sister asleep on his lap, their faces lit by yellow lamplight, he haltingly reads aloud a fantasy story, announcing a central theme, the vagaries of faith: “Though all were enthralled by [the doctor’s] exploits, the king said that those who believed him were stupid.”

Kummatty’s “enthralling exploits” are limited to charming the kids, who skip out of class to play with him, and conjuring sweets. Or so it seems, until he sets out for another village. The children chase after him and request one last dance, during which he hands over the masks, transforming them into literal animals whom Aravindan pictures in a series of goofy close-ups: lamb, calf, mare, monkey, peacock, baby elephant. With another flick of his staff, Kummatty makes them children again, but not before one snow-white pup escapes.

For a while, it seems that Chindan will forever remain stuck in this state. He explores the village, regarding human affairs with canine eyes, which the camera returns to again and again in close-ups. The effect is both touching and deeply unsettling, especially once he returns home, where his mother recognizes him. The family gloomily accept their new pet, who is given human meals and a small bed. In a reversal of the earlier image, his sister sits on the stoop with the napping dog in her lap, caressing him. Their ordeal only ends when Kummatty returns.

As a final magic trick, he warmly hugs the pup, who is reborn, through the power of love, as a boy. That embrace holds one of the film’s main lessons for children. The other comes in the final scene, when Chindan releases a caged parrot, granting him a freedom that all living creatures deserve. As it flies away, the camera tilts up to watch cranes migrating across the sky, asserting this right in its purest form.

Kummatty was well received by critics but did poorly at the box office. A similar fate befell Aravindan’s subsequent features, which are arrestingly dissimilar. Funding dried up once he parted ways with Nair. Moving from one rented house to another, he shot documentaries to make ends meet. In 1991, shortly before the release of Vasthuhara, a family saga that deals with Partition, he succumbed to a heart attack. “It would not be far from the truth,” his longtime associate Sasikumar Vasudevan reflected, “if I were to say that his death was caused by the complexities that arose from the financial crisis and his friends deserting him.”

His legacy is similarly fraught. Film histories identify Aravindan, along with Adoor Gopalakrishnan and John Abraham, as a key figure in the Malayali New Wave, which introduced socially engaged, expressive cinema to a regional industry stuck in formulaic melodramas about the downtrodden. This grouping is empirically true, if critically unhelpful. Unlike Gopalakrishnan and Abraham, who charted, with opposed political sympathies, the inexorable decline of Kerala’s feudal order, Aravindan was never much of a social chronicler, and his stylistic innovations have not proved influential. “I cannot think of a single Malayali filmmaker,” the cultural historian C. S. Venkiteswaran ruefully told me, “who is asking the kind of formal questions that Aravindan did.”

Nor is it easy to place him on the larger map of Indian art-house film. In his capacious study of parallel cinema, Omar Ahmed includes Aravindan among more than a dozen directors in a noncommercial, socially engaged tradition that flourished from the 1960s through the 1990s. It’s true that he adapted Indian literary texts, and was supported by the National Film Development Corporation, which Ahmed identifies as two signature traits. But his films have little of the political intelligence, and none of the anguish, that marks the oeuvres of representative directors like Shyam Benegal or Mrinal Sen.

Ahmed suggests that the Hindi auteurs Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani, and by extension Aravindan, contributed to parallel cinema by raiding the shastriya and lok kalas to develop an original cinematic idiom. Here, too, the differences are greater than the similarities: their tenor is austere and polemical, while his is gentle and playful. The critic Srikanth Srinivasan, taking the broader view, claims Aravindan as a precursor of contemporary contemplative cinema, a spiritually inclined tradition that includes Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Tsai Ming-liang. Restorations like this one of Kummatty, which at last brings Aravindan to an international audience, will allow others to pursue that connection.

Until then, one should probably resist the urge to repurpose the honorific he gave in a documentary title to the philosopher J. Krishnamurthy: “The Seer Who Walks Alone.” Aravindan’s self-assessment was more modest and congenial: “I do not understand what is mysterious about my films. After all, there are many mysteries in life too.”

More: Essays

The Man Who Wasn’t There: The Barber of Santa Rosa

For this existential noir, Joel and Ethan Coen drew inspiration from crime-fiction master James M. Cain’s lean, hard-boiled style and interest in the quotidian world of work.

Network: Back to the Future

Centered on the emotional unraveling of a failed newsman, this darkly prescient satire envisions the collapse of American society as we knew it through an unsparing critique of corporate media and capital accumulation.

Birth: Love Eternal

Jonathan Glazer’s enigmatic second feature explores the terrors of being desperate for love—and the vulnerability, loneliness, and difficulty in understanding other people that might drive this state.

Kiss of the Spider Woman: Revolutionary Transgressions

A resounding critical and popular success upon its release, Héctor Babenco’s adaptation of a literary masterpiece by Manuel Puig was an unprecedented cinematic fusion of a radical politics of sex with a sexual politics of revolution.