The Fall of Otrar: From the Ruins of Otrar

By Kent Jones

To honestly and justly describe evil and the unapologetic exercise of raw power is rare in life and rarer yet in cinema. It forces us to do the unthinkable: to examine ourselves, to abandon the assumption that we are a breed apart, temperamentally and even biologically incapable of harming others. We meet the challenge with disappointment, resignation, or dry disdain expressed in homilies, truisms, or theories lobbed into common life from comfortable distances.

I’m indulging in this prelude as a way of framing Ardak Amirkulov’s The Fall of Otrar, written by Alexei German and Svetlana Karmalita, husband and wife and longtime creative partners. This relatively unknown 1991 epic is one of the precious few films that looks evil in the eye without flinching. It fully deserves a place alongside Shoah and its satellite films Raging Bull and German’s own Khrustalyov, My Car! (1998). Indeed, The Fall of Otrar is so clear-eyed from start to finish that it approaches a state close to transcendence.

As is the case with German’s My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1985) and Khrustalyov, set during two different periods of the Stalin era, the narrative is so elemental that it barely exists. A Kipchak scout named Unzhu (Dokhdurbek Kydyraliyev), who has been sent from the ancient city-state of Otrar within the greater Khwarazmian empire to infiltrate and spy on Genghis Khan (Bolot Beyshenaliyev) and his Mongol hordes, returns after seven years with the unwelcome news that the khan is on his way to wipe out every trace of local culture and history. For the majority of the film, Unzhu endures round after round of humiliation and punishment as he tries to convince Kairkhan (Tungyshbai Dzhamankulov), the ruler of Otrar, of the coming apocalypse before it’s too late. From there, we are taken through the fall of the city step by savage step.

The narrative energy in The Fall of Otrar, just as in Khrustalyov, is generated by a beleaguered but headstrong character trying to cut through layer after layer of resistance to knowing the painful truth—the vanity of Kairkhan as a supreme leader, the duplicity of his Chinese advisers, the reflexive human habit of disbelief, and above all the sheer fact of torture and humiliation as the common currency of everyday life in this Eastern medieval world. If someone utters a thought that suggests a bad outcome, if they make a move or speak a word that somehow implies a violation of the absolute supremacy of the leader or the state, if they are even faintly suspected of anything at all, they are hung with chains from a crossbar in the blazing sun, burned with a hot iron, beaten to a pulp, or pushed to the ground and relieved of their tongue with iron shears. Unzhu is persecuted because he has committed the unpardonable sin of living among Genghis Khan’s hordes, no matter that he was instructed to do so.

In the waning days of the Soviet Union, German and Karmalita were commissioned to write The Fall of Otrar by Murat Auezov, a nationally renowned literary, political, and cultural figure who was then editor in chief of Kazakhfilm Studios. Auezov wanted an epic that reached far back in time to the lost civilization of Otrar and the beginnings of Kazakh culture. It took German and Karmalita two years to complete the script, and Auezov selected Amirkulov, then a graduate student (with a striking medium-length film to his credit, Tactical Games on Rough Terrain), as director.

The structure of Otrar is certainly all of a piece with German’s own work. But as a total film experience, it feels distinctly different from Khrustalyov, Ivan Lapshin, or German’s posthumously completed Hard to Be a God (2013, a years-in-the-making adaptation cowritten by German and Karmalita, traces of which can be felt in Otrar). “They were two of the most renowned filmmakers of Soviet cinema,” said Amirkulov in conversation with production designer Umirzak Shmanov. “We were, of course, very lucky to have them as the screenwriters. The script was extensive, extremely cumbersome, and completely uncompromising in the sense that they never settled for bypassing historical facts or circumstances, and they never came up with any easy solutions. On the one hand, it was very difficult to film. On the other hand, it was incredibly energizing because the script itself read like good literature. That’s why I’m grateful to fate for bringing me together with people like Alexei and Svetlana. I learned a great deal from their script because I had to put in a lot of effort, thought, and research to bring it to life. I even studied music, painting, read a lot of literature about the period, and watched films to match the material they had written.”

In German’s films, and in Otrar as well, we are dropped into a mazelike world with no apparent points of entry or exit, where nothing is certain and where nothing makes complete sense apart from absolute power and its merciless enforcement. As the films unfold, the horizontal narrative progression is overtaken by a vertical accumulation of details, repetitions, strange proclamations and rituals, sudden capricious assaults, and coded transactions, layer upon layer of unease gradually evolving into horror.

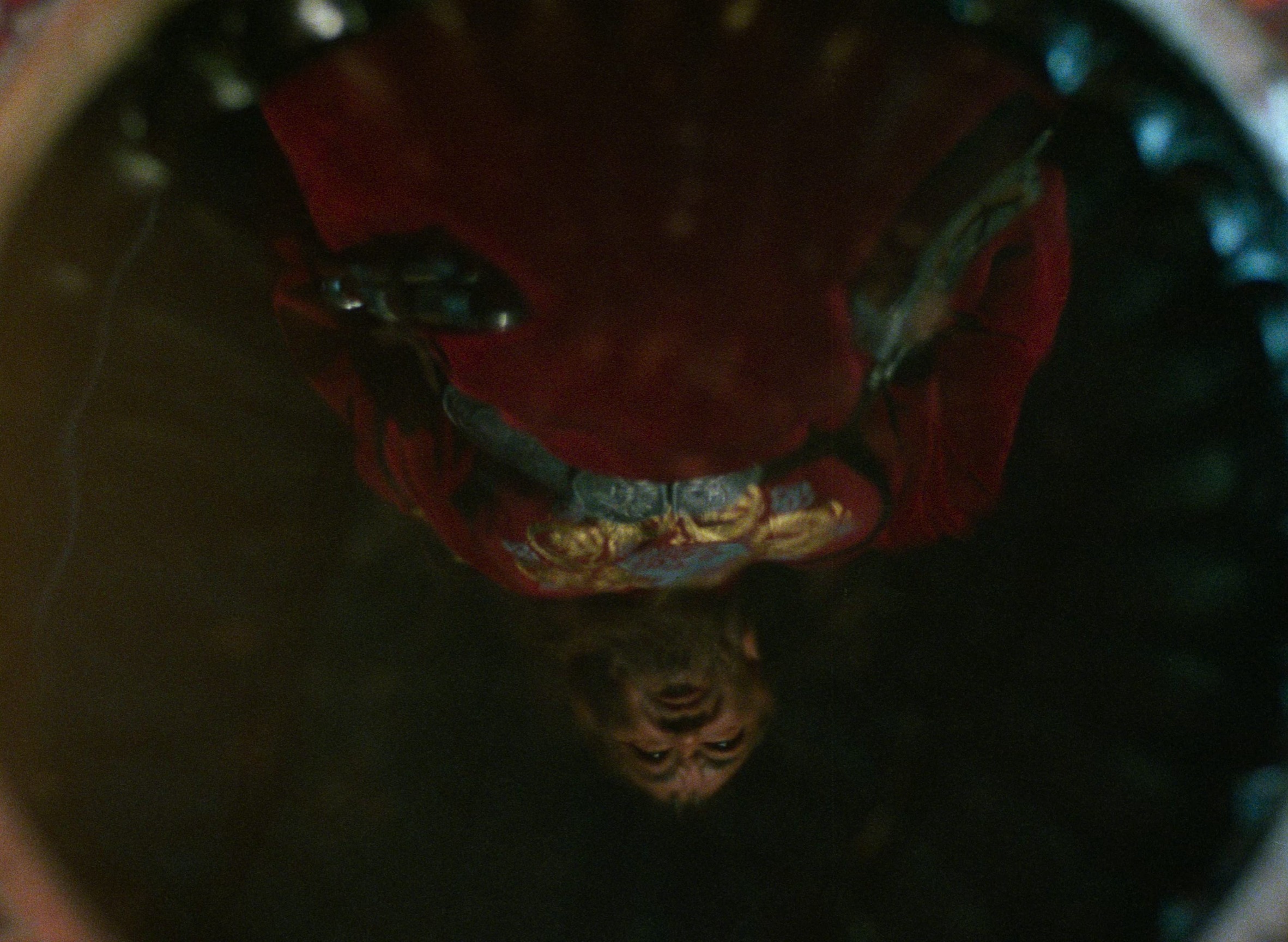

Amirkulov met the challenge of German and Karmalita’s massive script with a cinematic conception that goes far beyond mere visualization or dramatization. Where German in his own films deftly choreographs, orchestrates, and reiterates an atmosphere of chaos that edges and sometimes lurches into terror-laden absurdism, Amirkulov thinks graphically, texturally, and physically, all at once. He wanted Otrar to feel and move “as if it were all filmed in a past life, perhaps, in ancient times . . . So we had to work hard on the actors’ physiology, and their behavioral physiology, so that it would be as different as possible from modern times.” He also builds a very unusual and uneasy momentum, setup by setup. “I realized that I always needed to tighten the frame,” he told journalist Gulnara Abikeyeva in an interview. “I called this the ‘Kurosawa effect.’ This is a special form of concentration that creates a special rhythm.” Nothing in Otrar is framed or staged for beauty or repose; every cut is driven by tension rather than resolution.

There are no ordinary or strictly functional images or transitions in The Fall of Otrar. Every element of cinema is put to creative use. From the singular physical vocabulary, to the always unexpected shifts from sepia to vibrant color, to the extraordinary visual tactility (which suggests thatching or rough embroidery), Amirkulov’s film looks and moves like nothing else. “I didn’t aim to make a ‘historical epic,’” he told Abikeyeva. “The plot, costumes, sets—all surface elements—are historical. However, the internal dramatic arc, I think, has to be current, even a little bit futuristic.” In essence, Amirkulov fashions his own version of a “science fiction of the past,” the term Fellini used to describe his Satyricon.

I know I am not alone in finding it difficult to sort out or even try to keep track of all the fraying political allegiances and betrayals in this film, to figure out which people are in service to which power and to what degree, to understand what place the Turkic Kipchaks occupied within the greater Khwarazmian empire or the importance of Otrar’s proximity to the Silk Road and the Syr Dar’ya river. But in the end, historical and political clarity is not really the goal of the film. What is crystal clear, from start to finish, is the arc of destruction and dominance. In that sense, The Fall of Otrar is less historical than archetypal. The names and the particulars may change, but the drama is always the same.

For Auezov and his fellow Kazakhs, a film that on the one hand recreates the city-state of Otrar and on the other hand visualizes its complete destruction would evoke the memory of a more recent cataclysm: the Asharshylyk, or famine. Kazakhstan was hit with one famine in the early 1920s, a by-product of drought and the new Soviet policy of grain requisitioning that resulted in half a million deaths. The greater famine of the early thirties, which wiped out a third of Kazakhstan’s population and sent hundreds of thousands more on the refugee trail, had just one causal factor: the policy of Soviet collectivization, which simultaneously robbed the country of its harvests and livestock, destroyed the ecology of the vast grazing lands, and came very close to wiping out the country’s distinctive nomadic culture. For many years, whitewashed Soviet histories of the famine displaced on-the-ground accounts written in the Kazakh language, which was scorned by Moscow. Even in the era of perestroika, the overwhelming tragedy of the Asharshylyk could be dealt with in fiction only from an oblique angle. Films about the famine have only recently started to appear: they include Amirkulov’s most recent film, The Land Where the Winds Stood Still (2023).

With their depiction of Genghis Khan, Amirkulov, German, and Karmalita fashioned an archetypal omnivorous conqueror, evoking parallels from throughout recorded history, from Caesar to Napoleon to Hitler to Mao to Hutu leader Théoneste Bagosora to Bashar al-Assad of Syria. Amirkulov visualizes a catalog of horrifyingly brutal acts and details of medieval warfare and torture, climaxing in the now famous moment in which Genghis Khan’s men encase the captured and humiliated Kairkhan’s head in an iron mask and pour in molten silver to create a likeness of his head for display. But Amirkulov is no connoisseur of beautifully choreographed violence. Rather, he is concerned with the greater goal of reenacting the terrible, hair-raising momentum of dominance.

The film’s ground zero of absolute horror comes earlier, as a broken Kairkhan is laid down before Genghis Khan. After the conqueror offers his prisoner a hunk of roasted meat, he points to two old men sitting in a corner and speaks a magnificent soliloquy in a black, toneless baritone: “Look at them. They’re old scholars. They’re both from the same nation, yet they each ask me to skin the other one alive because one claims that God said one thing, and the other something different. And all this while horses enter their God’s house. I still haven’t decided whether I’ll let their nation survive or rot. While both of them are promising to prolong my life if I wipe the other one out. So why do you believe that I am wrong to trample on this land in order to build something different?” And, as the camera pans past double-dealing Chinese advisers stuffing themselves with the roasted meat, Genghis Khan adds a throwaway afterthought to Kairkhan: “I should be concerned about the things people will say about me a thousand years from now. Of course, you are just another detail, nothing more.” Kairkhan’s total spiritual death comes long before his horrific live embalming.

My love for Kazakh cinema began in 1996, when Philippe Garrel said to me, “There are some films that you should see.” He took my notebook and pen out of my hand and wrote down the name of a director and two of his films: Omirbaev, Kairat, Kardiogramma. He was absolutely right about Darezhan Omirbaev, and his film recommendations opened the door for me to the Kazakh New Wave, which properly began in the late eighties with Rashid Nugmanov’s The Needle and Serik Aprimov’s The Last Stop and was still gathering momentum a decade later. Sergei Dvortsevoy’s Bread Day and Highway, Amir Karakulov’s Last Holiday, Ermek Shinarbaev’s Revenge, the Omirbaev films . . . one revelation after another. And then The Fall of Otrar.

I saw the film for the first time at the 1999 San Francisco International Film Festival in a program of Kazakh cinema curated by Peter Scarlet. It left me open-mouthed, and I raved about it to everyone I knew. German and Karmalita were there for the program, and I met them every morning for breakfast at our hotel. I will never forget the Q&A, when a sweet woman stood up and asked them whether the man with the molten silver poured over his face had died in the process. “We can’t be sure,” began German’s deadpan response, “but the answer is probably yes.”

In 2004, I visited Central Asia. Alla Verlotsky and I had received a grant to curate and present a retrospective of films from the region. We visited Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan: an eye-opening experience, to put it very mildly. As much as I loved visiting Bishkek and Samarqand and riding through Tashkent (our guide, who spoke not a word of English, pointed out the window of our car and said, “Kent . . . Tashkent!”), as graciously received as we were in every country, my heart was with Kazakhstan, which we visited first.

There is a piquant and somewhat mysterious melancholy that runs through all of the great Kazakh films made during the era of perestroika and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This melancholy is abundantly present in The Fall of Otrar, in striking contrast with German’s mordant and much harsher sensibility. And it was present in the mood of the country itself—quiet, reserved, almost ghostly at times. Serik Aprimov explained to me that the word “Kazakh” translates roughly as “the people who wandered away from the center.” A temperamentally nomadic culture, partly a matter of geography—enormous chunks of its vast landmass are still unsettled and uninhabitable—and partly a matter of tragic circumstances that have left the nation’s history fragmented and scattered to the winds.

We visited Ardak at his vast farm in the mountains beyond Almaty, where wild horses roamed through high hills. He was a family man and a gracious host, and he was thankful for the attention to his film, which was at the time caught in some kind of strange political gridlock that lasted many years. He was an ebullient and almost flamboyant figure, anything but melancholy. But then, he had perfectly transmitted his country’s pervasive sense of melancholy cultural dislocation in the film itself. “I wanted to express my pain for us, the Kazakh people,” he told Abikeyeva. “The ancient city of Otrar was the cradle of our civilization, and we still haven’t climbed out of its ruins.”

There are two moments in this exalted film that point in the direction of hope, that give us truly honest depictions of affirmation in the face of calamity. At the halfway mark, just before the arrival of the Mongols, the librarian of Otrar seals himself off with all his precious manuscripts in a collapsing underground passage, in hopes of a rediscovery centuries or even millennia later: it’s a stirring affirmation of all cultural heritage.

And then there is the ending. Unzhu, who has done everything he can to save Otrar, wanders through the ruins of his holy city, musing on the fate of those once considered all-powerful, now reduced to martyrs or supplicants. Before he wanders out of the frame and the credits start rolling, he speaks the last, simple words to himself: “You know, our Otrar stood longer than any other city . . . so I have heard.” What a fitting ending to this remarkable film.

More: Essays

The Man Who Wasn’t There: The Barber of Santa Rosa

For this existential noir, Joel and Ethan Coen drew inspiration from crime-fiction master James M. Cain’s lean, hard-boiled style and interest in the quotidian world of work.

Network: Back to the Future

Centered on the emotional unraveling of a failed newsman, this darkly prescient satire envisions the collapse of American society as we knew it through an unsparing critique of corporate media and capital accumulation.

Birth: Love Eternal

Jonathan Glazer’s enigmatic second feature explores the terrors of being desperate for love—and the vulnerability, loneliness, and difficulty in understanding other people that might drive this state.

Kiss of the Spider Woman: Revolutionary Transgressions

A resounding critical and popular success upon its release, Héctor Babenco’s adaptation of a literary masterpiece by Manuel Puig was an unprecedented cinematic fusion of a radical politics of sex with a sexual politics of revolution.