Chronicle of the Years of Fire: Chronicle of a Nation in Revolt

By Joseph Fahim

Since its release in 1966, Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers has been hailed as the quintessential cinematic document on Algeria’s War of Independence (1954–62). The rawness, immediacy, punchiness, and sheer dynamism of the picture have never gone out of fashion, while its unabashed advocacy for a just armed resistance against an oppressive rule inspired various political movements around the world.

Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina’s Chronicle of the Years of Fire (1975) is a different beast: a sweeping tale of Algeria’s peasant uprising set in the years preceding the revolution and mostly eschewing the kinetically edited violence that made Pontecorvo’s Oscar nominee a timeless sensation. Chronicle—which, unlike Pontecorvo’s European-cofinanced film, is an Algerian production through and through—is a quieter affair. Its brewing fury is more contained. Its characters are less impulsive, saddled with the burden of subjugation. Its tone is more mournful: a memorial to the lives lost before the nation earned its hard-fought freedom.

It is also one of the most singular Arab films. Though historical productions were not unknown in the region’s cinemas, Chronicle stands out as a widescreen political epic that uses dialogue sparingly, anchored by an atypically subdued protagonist and culminating with an uncathartic ending. It remains the sole Arab and African Palme d’Or winner: the film that placed North African cinema on the map and changed the course of the region’s then-budding national cinemas—government-backed film industries emerging from the shadow of colonization, which were initially employed as tools for nation-building.

Born in the northern province of M’Sila in 1934 to a working-class family of farmers from the highlands, Lakhdar-Hamina became infatuated with cinema at an early age. After majoring in agriculture, he switched focus and studied law in the French town of Antibes. Like all young Muslim Algerian men at the time, Lakhdar-Hamina received a draft summons for the French army in 1958, but opted to flee and join the Algerian resistance in Tunisia. There, he learned to make films after joining the media department of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA), the government-in-exile of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN). A year later, the FLN sent him to study cinematography at the renowned FAMU film school in Prague.

During this period, the French army arrested, tortured, and killed Lakhdar-Hamina’s father—an event that would shape Lakhdar-Hamina’s life and work. He began his career in 1959 with a number of shorts he codirected with FLN colleague Djamel-Eddine Chanderli that exposed the brutality of the French rule while mobilizing Algerians to back the efforts of the National Liberation Army (ALN) in liberating the country. After Algeria gained independence in 1962, Lakhdar-Hamina returned home, and his debut feature, The Winds of the Aures (Rih al awras, 1966), announced the birth of postcolonial Maghrebi cinema. A moving account of a widowed mother’s doomed search for her son who has been abducted by the French army, the film carries the hallmarks of Lakhdar-Hamina’s cinema: rural settings, ordinary working-class characters, magisterial landscapes, poetic compositions, and carefully calibrated performances. The Winds of the Aures was the first Algerian picture to compete in Cannes and the first Arab entry to win the festival’s award for best first film.

His sophomore feature, Hassan Terro (1968), remains the most adventurous entry in his oeuvre and his most popular film at home: a high-concept black comedy centering on a compliant family man who gets mistaken for a notorious terrorist. Starring and cowritten by the great Amazigh comedian Rouiched, this pitch-perfect satire underlined Lakhdar-Hamina’s preoccupation with the less heroic, morally flawed facets of the revolution—a recurrent theme in his work. He followed this with Décembre (1973), a military drama centering on a French officer who gets struck by a crisis of conscience when he witnesses the use of systematic violence in the interrogation of FLN fighters.

Lakhdar-Hamina wrote Chronicle of the Years of Fire in 1971 with Rachid Boudjedra and director Tewfik Fares, with whom he had previously collaborated on The Winds of the Aures. The project was shelved for three years because of a lack of funding before Houari Boumédiène, the second president of Algeria, stepped in to bankroll the film, which was estimated to be the most expensive Algerian production to date.

Partially inspired by the director’s childhood, the film is divided into six chapters, beginning in 1939 with the rising anticolonial sentiment among peasants, and concluding in 1954 with the outbreak of the War of Independence. Greek actor Yorgo Voyagis plays Ahmed, a farmer and young father struggling to make ends meet as his village is struck with a drought that has driven some of his neighbors to leave and sell their lands. The first part of the film (“The Years of Ashes”) explores tribal disputes over water and the political isolation of the rural part of the country, which was neglected and ostracized by the French government. The evocation of pagan rituals and of the spirit of the desert as the peasants seek to break the drought astutely highlights the country’s Islamic Arab and Berber heritage that existed long before the 1516 Ottoman Regency of Algiers. This heritage, this history, was long denied by the French, who habitually insisted that Algeria was a terra nullius—an empty land with no civilization that they rescued from the abyss of ruin.

Lakhdar-Hamina does not explicitly implicate the French in the farmers’ misfortune and routine displacement, but history indicates that the colonial government’s expansive scorched-earth tactics targeted irrigation systems, wells, and water reserves; the qanats, seguias, and traditional irrigation channels were often destroyed by the French in disciplinary expeditions.

Helpless and impatient, Ahmed heads to a larger city seeking steady work. There he is greeted by Miloud, a wise man speaking in rhythmic verse, whose incendiary, bluntly truthful commentary is judged a sign of madness by his fellow Algerian townspeople. Miloud is the beating heart of the film: the revolutionary spirit exposing the brutality of colonization and heralding the end of French rule. Rouiched, the star of Hassan Terro, was supposed to play Miloud; his decision to drop out forced Lakhdar-Hamina to play the part himself. Miloud guides Ahmed and his family to his new town, where the French presence is more palpable than in the farmlands, pointing out the luxurious houses of the French that stand in contrast to the barren lodgings of the Arabs, and the intrusive churches.

“Here, you will find those who rule us with contempt,” Miloud tells Ahmed.

Ahmed finds life in the city nowhere near as prosperous or fair as he had envisioned: he experiences the tyranny and callousness of the French employers who treat Algerian workers like cattle. A rebellious action against his sadistic employer lands him briefly in prison, where he is assaulted by the racist police. He jumps from one menial job to the next before a typhus outbreak shatters his town. In one of the starkest scenes of the picture, which gets to the heart of colonial rule, the French are whisked away from the city as the Algerians are confined within it until the epidemic devours their weakest. By choosing to treat the evacuated French as a monolithic whole with no individuality, Lakhdar-Hamina implies that, in this system of oppression, the silence and dutifulness of every compliant citizen maintain such order.

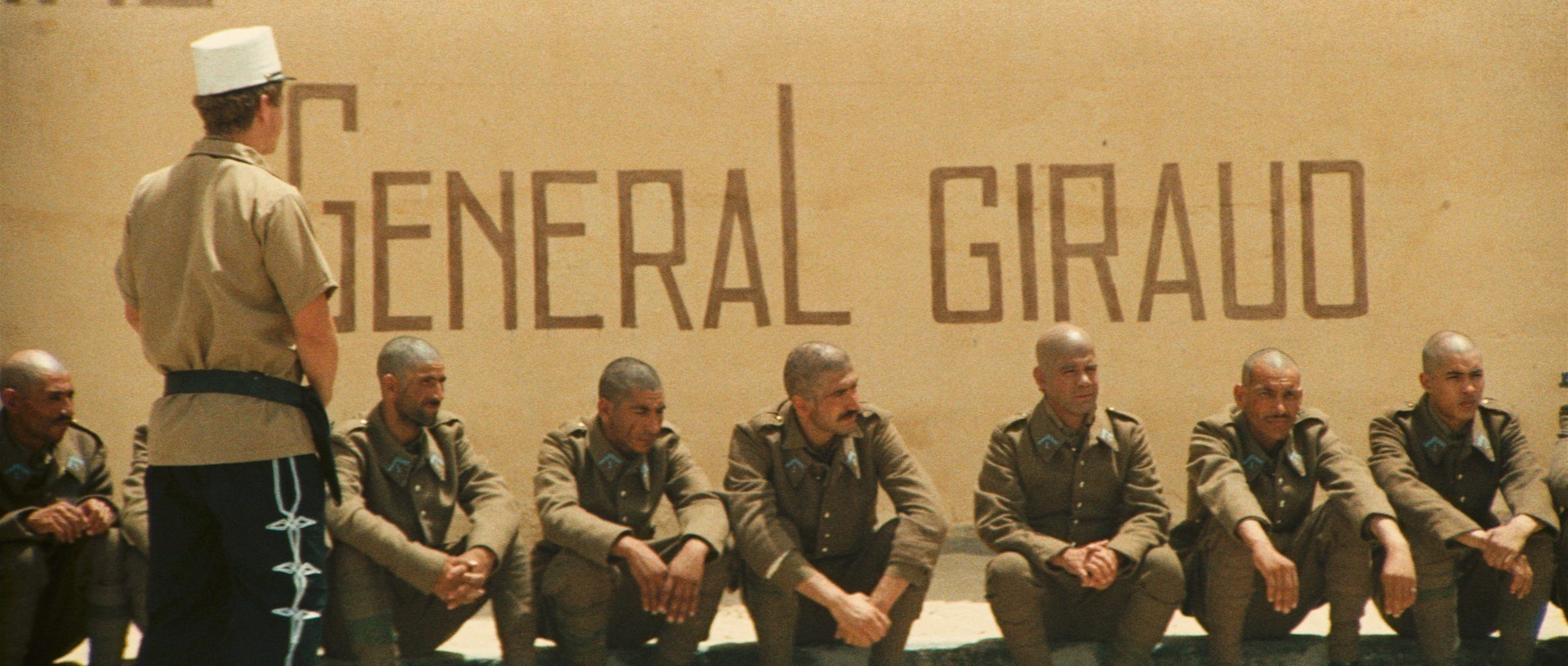

Jaded and ireful, Ahmed returns to his home village to find conflicts over water still raging, and starts mobilizing his tribesmen to rise up against the colonial rulers and blow up the dam holding water for the French elite. He gets caught and is conscripted into the French army as World War II breaks out. The initial excitement about Hitler soon dissipates—most Arab countries under European colonization took the Nazis’ side at the beginning of the war, hoping they would defeat the British and French. One farmer eventually deduces that “Hitler will annihilate us. He said that the Arabs are the fourteenth race, after toads.”

When Ahmed returns home on May 8, 1945, the day Allied forces sealed their victory over Germany, he finds massive numbers of his countrymen murdered by the French—a reference to the Sétif and Guelma massacre, when French authorities and settlers went on a killing rampage in retaliation for the 102 people killed by Algerians after the French police shot protesters in the northeastern part of the country. Historians estimate the number of Algerian fatalities to be anywhere from three thousand to thirty thousand.

In the final chapters of the film, the seeds of an organized movement start to form with the arrival of Si Larbi (celebrated theater actor Larbi Zekkal), a recently released political prisoner who challenges both the collaborating Algerian provincial rulers and the religious authorities that strive to maintain the status quo. Some of the film’s most provocative ideas are introduced in this segment. Lakhdar-Hamina’s skepticism toward religion—as a tool for submission and a pretext for inaction, if not an archaic tradition—is palpable throughout the story, but comes to the forefront here.

Si Larbi’s assertion that “what has entered with violence must leave with violence” might be an oversimplification of the argument for armed resistance, but Frantz Fanon’s meditations on the inevitability of the usage of violence against a self-serving colonizer can be traced throughout the film’s narrative. “Colonialism is not a thinking machine, is not a body endowed with reason. It is violence in the state of nature and can only bow to greater violence,” Fanon wrote in The Wretched of the Earth (1961).

Fanon’s emphasis on the essential role of peasants in insurrection is integral to the progression of Lakhdar-Hamina’s story. “The peasants alone are revolutionary, for they have nothing to lose and everything to gain,” Fanon wrote. “The starving peasant, outside the class system, is the first among the exploited to discover that only violence pays.” Both Ahmed and Si Larbi reach the point where they have nothing to lose. Decades of futile dialogue with the French enemy have done nothing to alleviate Algerian suffering or eradicate poverty or restore equality. The use of violent resistance, Lakhdar-Hamina illustrates, arises from desperation: a last resort emanating from the failure of every other conceivable solution.

By the time the film concludes on November 1, 1954—the Toussaint Rouge, when seventy synchronized militant attacks were waged by the FLN against the French police, the military, and European settlers to commence the War of Independence—the transformation of Ahmed from a powerless peasant into a freedom fighter is complete. Yet neither he nor Miloud receive the grand send-offs associated with heroes in Hollywood blockbusters.

The first part of the film accentuates the heaviness of time. The cumbersome weight of oppression and structural exclusion informs the gazes and movements of the characters. Lakhdar-Hamina’s camera moves wearily and somberly, reflecting the despondency of people afforded few choices. Over the course of the film, the camera gradually picks up the pace to mirror the mounting anger of the peasants and the evolution of the resistance. Lakhdar-Hamina correlates the simmering fury and contagious spiritedness of rebellion with the casual injustice and violence of the unsustainable status quo.

The cinematography by the great Marcello Gatti—director of photography on The Battle of Algiers—eschews visual mannerism and moody lighting, relying instead on a matter-of-fact approach. The early sparse frames gradually give way to richer compositions that grow mythical in aura as the resistance snowballs. Youcef Tobni—editor of Hassan Terro, the Algerian classic The Opium and the Baton (1969), and Med Hondo’s masterpiece West Indies: The Fugitive Slaves of Liberty (1979)—brings a discernibly graceful musicality to the structuring of the different tempos of the film.

Lakhdar-Hamina sprinkles the film with close-ups of ordinary Algerians—a naturalistic touch nodding to Pier Paolo Pasolini. Ahmed, though, is mostly framed within bigger canvases that recall the work of Alexander Dovzhenko in Arsenal (1929) and Earth (1930). The intertwining of individual self-actualization with national emancipation is a recurrent theme in Lakhdar-Hamina’s work. Ahmed’s journey is more symbolic than psychologically driven. In times of collective upheaval, the director suggests, the land towers over individual heroism—another theme lifted from Fanon’s championing of collective struggle and the creation of “new man.”

The sole weakness of the picture is the diminutive role of women. Lakhdar-Hamina’s women were largely relegated to either the sacrificial mother (Aures, 1982’s Sandstorm) or the unattainable object of affection (The Last Image, 1986). Chronicle is no different. The only noticeable female character is Ahmed’s unnamed, silent wife, played by Moroccan actress Leila Shenna. Arab critics defended Lakhdar-Hamina by asserting that not all Algerian women were the freedom fighters of The Battle of Algiers, but the complete absence of any female character of note does expose a major and consistent shortcoming in the director’s storytelling.

The Arabic title of the film, Waqaa seneen al-jamr (Chronicle of the Years of Embers), refers to the epoch of tribulations preceding the War of Independence. For commercial purposes, “embers” was changed to “fire” in the English-language title, as distributors deemed it more direct and attractive. This English title—which Lakhdar-Hamina approved—had a more dramatic connotation that hints at the brewing of the revolution as charted in the latter chapters of the films.

Chronicle of the Years of Fire was, to be sure, incendiary on its release. Lakhdar-Hamina was attacked both in France and at home. In Cannes, he received death threats from former members of the far-right paramilitary group OAS (Organization of the Secret Army), which never let go of its colonial dreams. In Algeria, while his Palme d’Or win was broadly celebrated, some critics frowned upon the film’s depiction of the internal conflicts within the revolution and the concentration on the agrarian side of the nation at the expense of the new industrial Algeria.

Between this triumph and his death on May 23, 2025, the same day Cannes celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of Chronicle, Lakhdar-Hamina made only three more films, all of which revolved around colonial-era Algeria. Swiftly after his Palme d’Or win, Algeria had already moved on. Merzak Allouache soon became the nation’s hot new auteur thanks to a series of highly successful dramas capturing the growing mood of urban alienation. The bloody conflict between the Algerian government and Islamist groups that resulted in the 1992–2002 civil war (the Black Decade) saw a suspension of film production and the destruction of most of the nation’s cinemas.

Younger generations of Algerians remain oblivious to Lakhdar-Hamina, while novice directors have been drawn to the post-nineties films of Sofia Djama, Damien Ounouri and Adila Bendimerad, Karim Moussaoui, and Lyes Salem—the Algerian New Wave. Lakhdar-Hamina’s ambivalent position toward the Arab Spring and his reluctance to criticize Algeria’s succession of autocrats who exploited the revolution to cover their failures raised questions about his relationship with the ruling system.

The influence of the nation’s colonial past, however, never left Algerian cinema. The various dramatizations of the era—Benamar Bakhti’s Buamama (1985), Rachid Bouchareb’s Days of Glory (2006), Saïd Ould Khelifa’s Zabana! (2012), Djaffar Gacem’s Heliopolis (2021)—were vastly influenced by Lakhdar-Hamina’s work, while Ounouri and Bendimerad’s blockbuster hit The Last Queen (2022) vied to take up the baton from the master in continuing to construct Algeria’s colonial-defying national myths.

The recent rise of the French far right and its dismissive position toward the country’s colonial past has cast Lakhdar-Hamina’s work in a new light. As nationalism and populism encroach on Europe once more, Chronicle of the Years of Fire may cease to be seen as the relic of a bygone era and finally be recognized as what it essentially is and always was: a courageous endeavor of historical revisionism, a defiant and loving act of rebellion against a mighty colonial giant once deemed unconquerable.

More: Essays

The Man Who Wasn’t There: The Barber of Santa Rosa

For this existential noir, Joel and Ethan Coen drew inspiration from crime-fiction master James M. Cain’s lean, hard-boiled style and interest in the quotidian world of work.

Network: Back to the Future

Centered on the emotional unraveling of a failed newsman, this darkly prescient satire envisions the collapse of American society as we knew it through an unsparing critique of corporate media and capital accumulation.

Birth: Love Eternal

Jonathan Glazer’s enigmatic second feature explores the terrors of being desperate for love—and the vulnerability, loneliness, and difficulty in understanding other people that might drive this state.

Kiss of the Spider Woman: Revolutionary Transgressions

A resounding critical and popular success upon its release, Héctor Babenco’s adaptation of a literary masterpiece by Manuel Puig was an unprecedented cinematic fusion of a radical politics of sex with a sexual politics of revolution.