Return to Reason: Four Films by Man Ray: Optical Dazzle

Man Ray recounted his entrée into filmmaking with appropriate cinematic flair. As he tells it in his memoirs, he had bought a small movie camera and “made a few sporadic shots . . . Vaguely I thought that when I had produced enough material for a ten- or fifteen-minute projection, I’d add a few irrelevant captions . . . and regale my Dada friends.” But when Tristan Tzara, the animator-in-chief of that radical arts movement, appeared with the printed program of a Dada event to be held the following evening, listing a film by Man Ray as one of the featured attractions, he was spurred to finish it overnight: panic as the mother of invention. In reality, Man Ray’s diary suggests that he knew of the handbill well in advance of the July 6, 1923, performance and had set aside ample time to complete the project—but why spoil good drama with mundane facts?

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia in 1890, Man Ray had early on participated in the New York version of Dada via his friendships with Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia. He then emigrated to France, arriving on Bastille Day 1921, and immediately fell in with the Paris Dadaists—including André Breton, Louis Aragon, Robert Desnos, and Paul Éluard, all of whom would help launch the surrealist movement a few years later. Known primarily for his avant-garde photographs—Le violon d’Ingres (1924), a woman’s back adorned with twin f-holes, is one of the iconic images of the twentieth century—Man Ray also created many famous portraits and fashion shots, and helped invent processes such as solarization, in which a photograph is exposed to sunlight to yield a halolike outline. Alongside these works, he produced numerous paintings, wittily subversive objects (including the 1921 sculpture Gift, a flatiron with a row of tacks down the front), and stylized chess sets. His foray into cinema was one more manifestation of a restless and innovative mind: as he later wrote, “My curiosity was aroused by the idea of putting into motion some of the results I had obtained in still photography.”

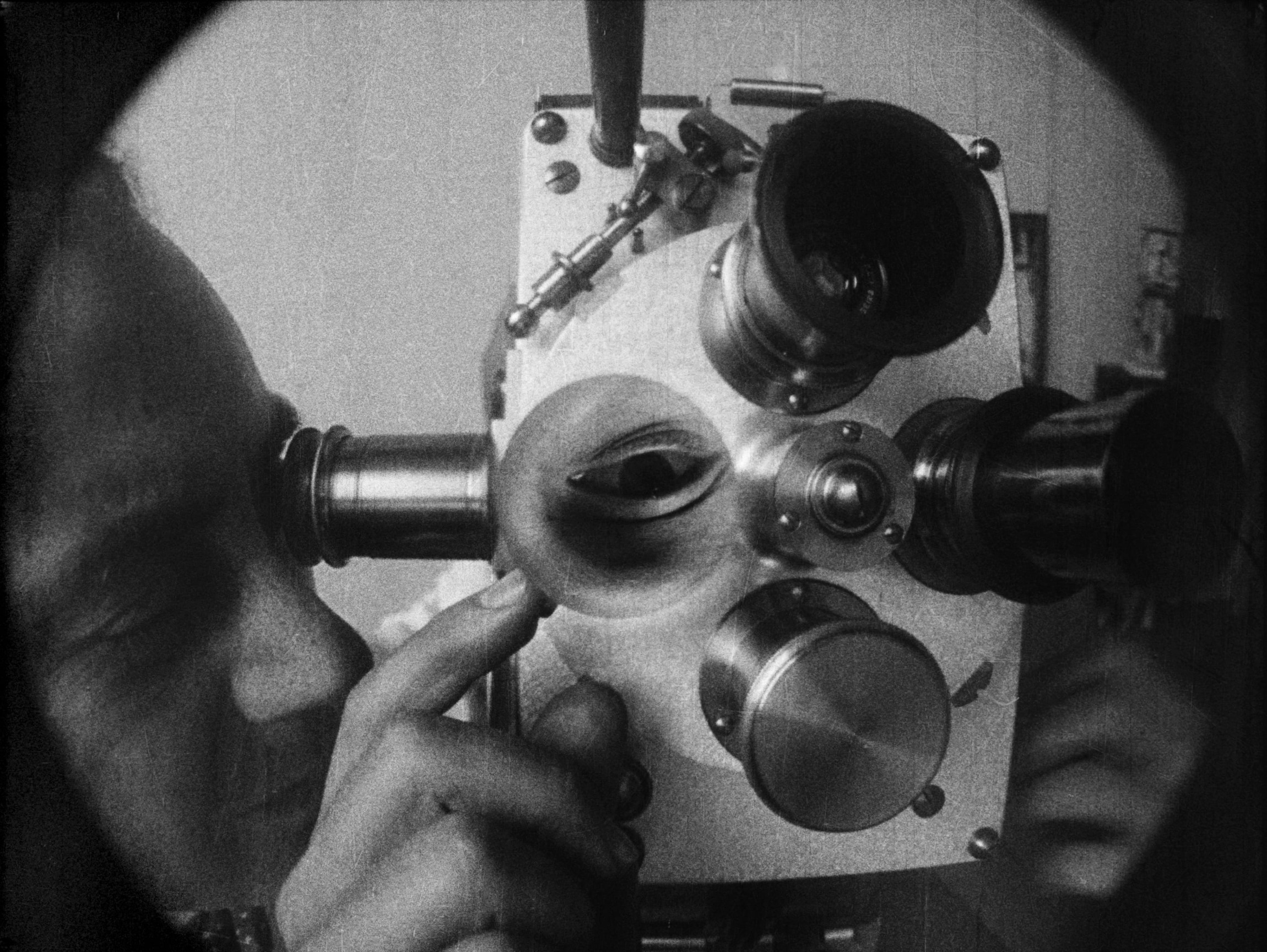

To flesh out the footage he had already shot, Man Ray cut up a roll of unexposed film in his darkroom and, “like a cook preparing a roast,” sprinkled it with salt and pepper, as well as thumbtacks, pins, rings, springs, strings, and other household hardware. It was an extension of a process he had recently developed and baptized the “rayograph”: a cameraless form of photography in which objects are placed directly onto photosensitive paper and subjected to light, yielding ghostly X-ray images on a black background.