Él: Mad Love

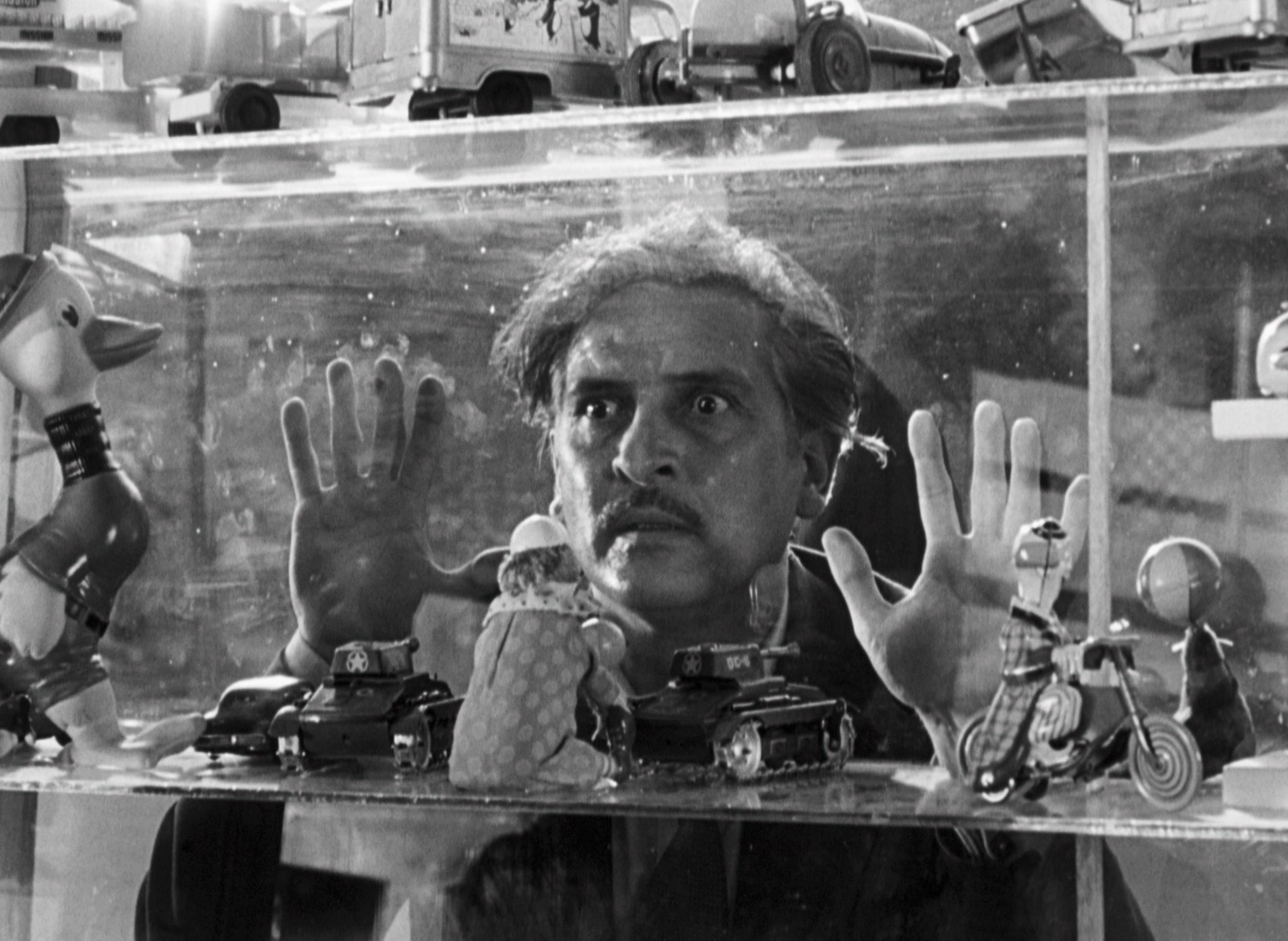

You could say that Él is extraordinary for its dissection of pathological jealousy, or because it captures, through hyperbole, the machismo of mid-twentieth-century Mexico. But these readings, though valid, don’t capture the full scope of the film’s artistry. Despite being relatively unknown among Mexican audiences, Él is one of the most fascinating works in the history of the nation’s cinema because it slyly combines the conventions of popular Mexican filmmaking with the surrealist sensibility that made its director, Luis Buñuel, a legendary figure in his native Spain—all while catching viewers off guard and immersing them in its protagonist’s delirium.

After Buñuel left his home country in 1936, soon emigrating to America and eventually establishing himself in Mexico, he directed many films that were much less subversive than those for which he had become known in his early career, most notably Un chien andalou (1929) and L’âge d’or (1930). In what has been called his “Mexican period,” Buñuel found himself hemmed in by the local industry’s demands and moved toward a cinema anchored in realism. But he never renounced his transgressive vocation. “I treasure that access to the depths of the self which I so yearned for,” he writes in his autobiography, My Last Sigh, “that call to the irrational, to the impulses that spring from the dark side of the soul.”

Though Él answers that call unforgettably, Buñuel was slow to admit that the film’s obsessions were so close to his own. When it didn’t win any prizes at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival and the Mexican press asked him about its “failure,” he defensively argued that the film was valuable for its illustration of a clinical disorder. In his view, Él wasn’t a movie for festivals but was interesting because it was “based on psychopathological studies and real-world experiences.” Years later, despite his declared contempt for psychology, he proudly repeated the story that psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan admired the movie and had shown it in his seminars.

The “real-world experiences” that Buñuel referred to came from Spanish writer Mercedes Pinto, whose 1926 novel Él describes in first person the hell that she had lived through in her marriage to her first husband. Though the book is presented as a work of fiction, Pinto opens it with a “clarification” in which she essentially reveals it to be a chronicle of her own life up to that point. The story proper begins on the couple’s honeymoon, when the unnamed protagonist attacks his guests for flirting with his wife. His paranoia grows until it results in a suicide attempt that finally alerts doctors to his condition. His physical decline—and not his obvious mistreatment of his spouse—is what leads to his institutionalization. Pinto underlines the indifference of the medical, legal, and religious authorities, the last of whom she blames for forcing her to stay married: in 1920s Spain, divorce was forbidden, in large part because of the influence of the Catholic Church. She even asked jurists and psychiatrists to write prologues and appendices for the book, hoping to inspire reforms.