If anyone could update the cinematic language of film noir for today’s audiences, I thought, it would be Guillermo del Toro. So I wasn’t entirely shocked that his next film did exactly that, though I was surprised—and delighted—that he had chosen William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 fever dream of a novel, Nightmare Alley, as his source material. Its mix of primal behaviors, the occult, and visceral horror made the book ripe for reinterpretation by a director steeped in genre, forever ready to bend it to his own iron will.

We must begin, however, with Gresham himself. Born in Baltimore and raised in Brooklyn, he learned of the material that seeded his first novel and magnum opus, Nightmare Alley, during his time as a soldier in the Spanish Civil War, when he met an “old-time carny” named Joseph “Doc” Halliday. According to Gresham’s 1953 nonfiction book Monster Midway: An Uninhibited Look at the Glittering World of the Carny, Halliday regaled Gresham with stories of carnival life and its colorful characters—including the lowly geek, who horrified and thrilled audiences by eating live animals, particularly chickens and snakes.

Geeks, according to Halliday, are made by desperate longing for a combination of alcohol, drugs, and a place to sleep. “The story of the geek haunted me,” wrote Gresham. “Finally, to get rid of it, I had to write it out.” At the start of his novel, Gresham shows young Stanton Carlisle hanging back, “under the blaze of a naked light bulb,” as he watches the geek at a carnival—“a thin man who wore a suit of long underwear dyed chocolate brown,” with a black wig that “looked like a mop . . . The brown greasepaint on the emaciated face was streaked and smeared with the heat and rubbed off around the mouth.”

Carlisle, lean, blond, twenty-one, and fascinated by this spectacle, is thus initiated into the carny world, learning his tradecraft—and tradegraft—from the likes of the owner, Clem Hoately; Zeena the mind reader (who takes Stan’s virginity); her acutely alcoholic husband, Pete; strongman Bruno; and Molly Cahill, the Electric Girl, Stan’s seeming salvation, his ticket out of carny life and into high-class territory as a mentalist for ritzy audiences. He eventually tries to run a con with an alluring psychiatrist named Lilith Ritter, who bests him at nearly every turn.

Just as the story begins with Stan observing the geek, it ends with others observing Stan in similarly fallen straits. The tarot cards have foretold it but so, too, has his desire for alcohol. Gresham writes of the latter with such clarity that Nick Tosches, in his introduction to the New York Review Books reissue, concluded: “Booze is so strong an element in the novel that it can almost be said to be a character, an essential presence like Fates in ancient Greek tragedy. The delirium tremens writhe and strike in this book like the snakes within.”

A year after its publication, Nightmare Alley was made into a film with Tyrone Power in a career-making performance as Stan Carlisle, Joan Blondell as Zeena, and Helen Walker as Lilith. But the film seemed to be cursed, and it was taken out of circulation within weeks of release. As the film writer Kim Morgan, who cowrote the screenplay for her husband del Toro’s version, observes in an excellent essay on the 1947 film, “One wonders how those first audiences . . . did feel seeing their matinee idol in such a brutal chronicle, so fascinated by the geek. They could not have forgotten it. And as the movie became so elusive through the years, the picture and Power’s performance must have felt like an especially feverish dream they once had. A delirium. A beautiful nightmare.”

Power’s version of Carlisle depends on the actor playing against type, subverting the debonair roles that the studio system had tasked him with playing again and again. The situation is a bit different for Bradley Cooper, whose acting career has run the gamut from hero to villain, and who at the time of Nightmare Alley had just come off his 2018 remake of A Star Is Born, in which he plays an alcoholic star on the decline (perfect preparation for del Toro’s film). By the time Cooper’s version of Stan takes in the soiled carny world, he is already running from something monumental in his not-as-young life: the violent death of his violent father. The change in backstory from book to film adds to the torment of the character, helping to make Cooper’s rendition particularly memorable.

Del Toro stacks his Nightmare Alley with outstanding performances: Willem Dafoe as the garrulous Clem; Ron Perlman threatening sweet menace as Bruno; Toni Collette electrifying the screen as Zeena, in an exhausted marriage to Pete, given extra gravitas by David Strathairn; Rooney Mara ever winsome (but assertive when it counts) as Molly; and Cate Blanchett channeling Marlene Dietrich as Lilith Ritter. Even small roles are imbued with extra pathos and menace, especially Mary Steenburgen as a woman grieving her dead child and Holt McCallany as a bodyguard ready to defend his employer to the death.

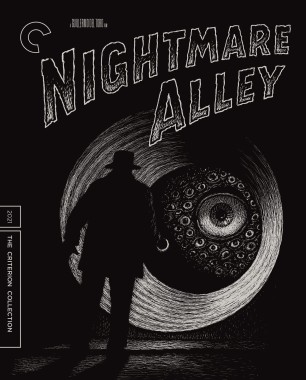

Though del Toro’s original version, released worldwide in December 2021, was in sumptuous color, like his previous films, a black-and-white version followed it into theaters just a few months later; this release presents a new cut of the film, under the title Nightmare Alley: Vision in Darkness and Light, also in black and white. A noir story demands a noir palette, which makes del Toro’s filmic references to the likes of Out of the Past (released the same year as the original Nightmare Alley film) and Night and the City (1950) even more potent in their depiction of certain doom mixed with louche glamour.