Altered States: Visions and Divisions

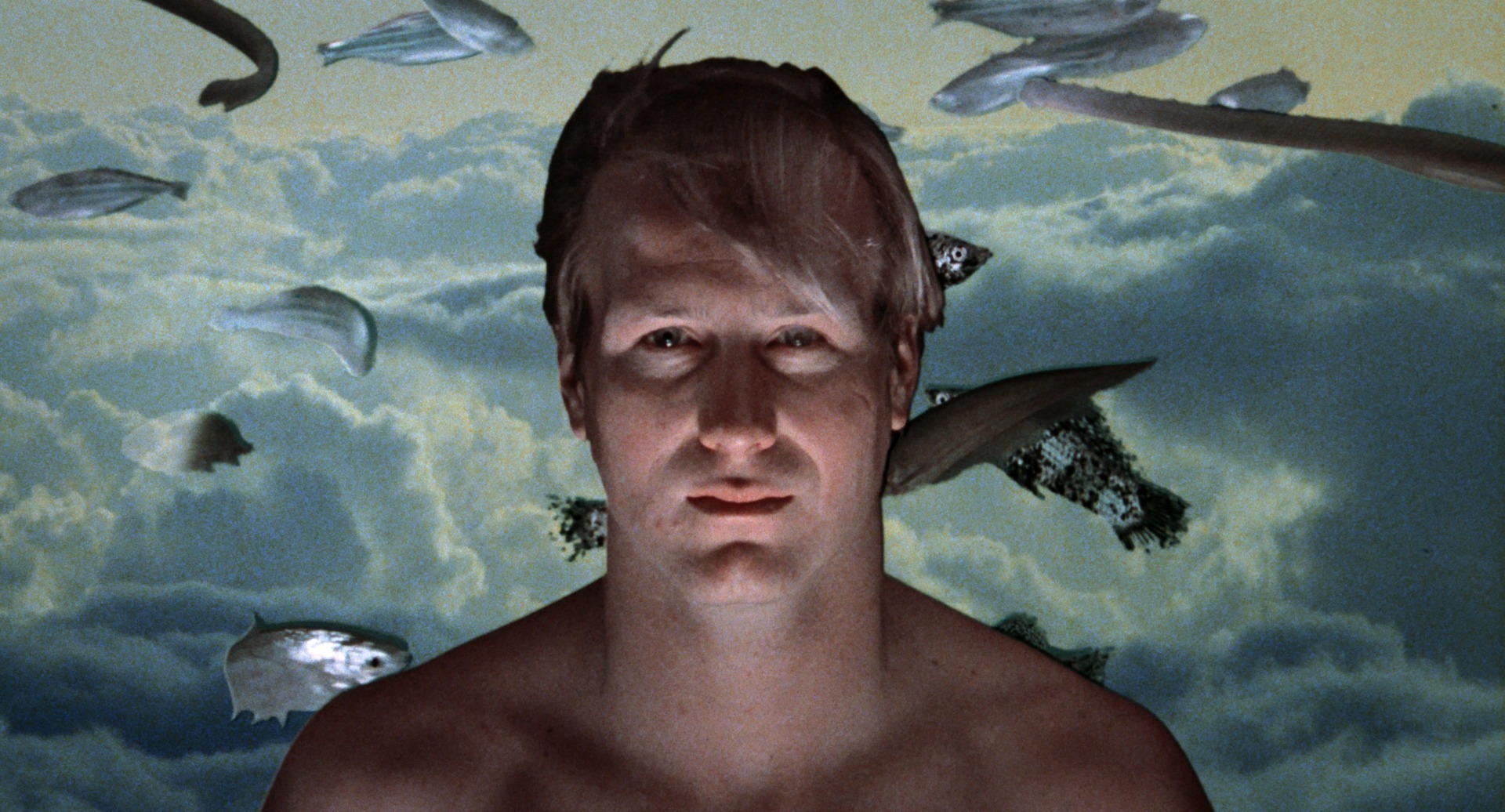

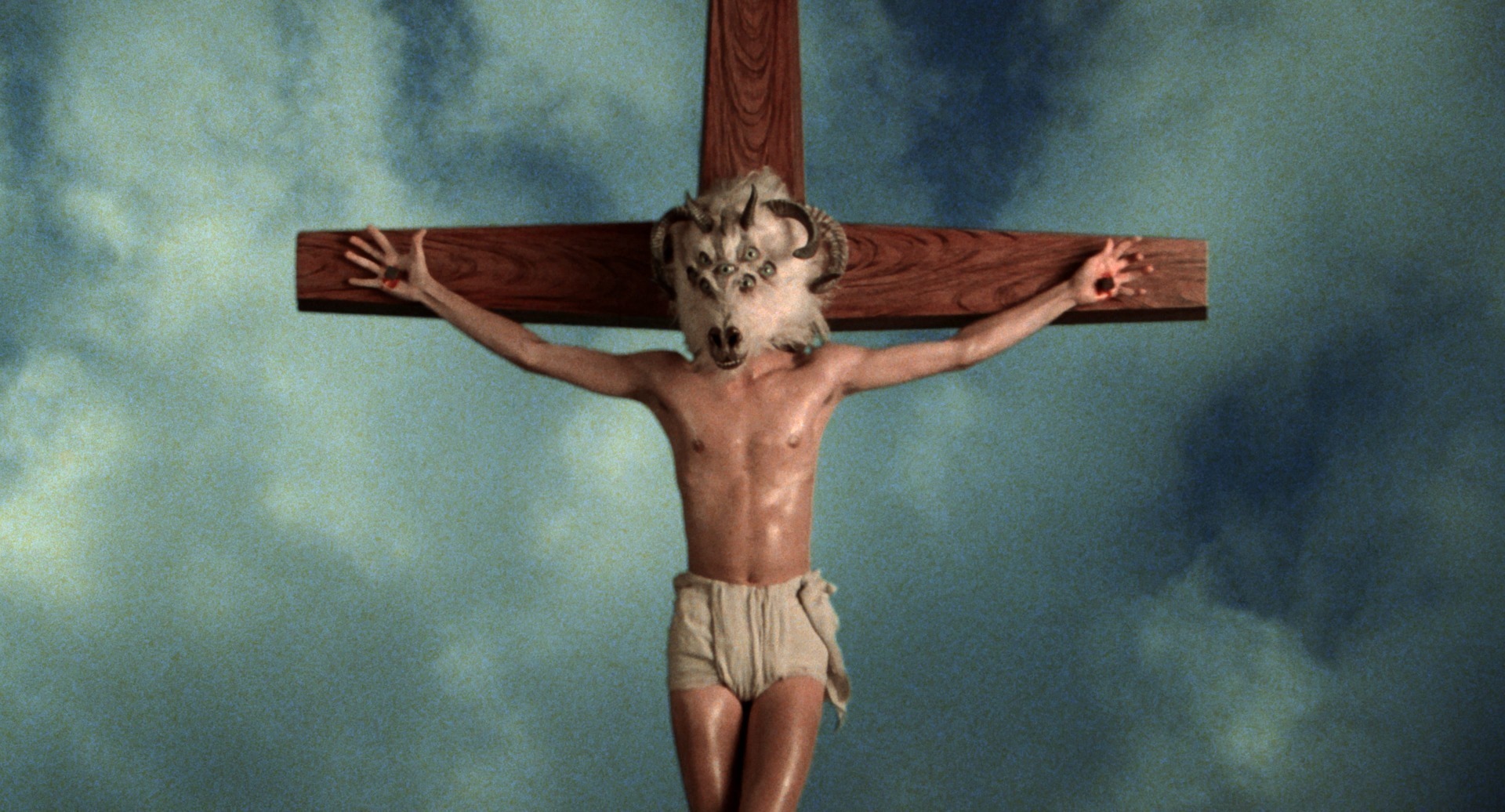

Fireworks crackle inside a cave. A snake tightens its coils around a man’s head. A couple in Edwardian dress eat ice cream against a backdrop of merry yellow flowers made sinister by their lush, inverse-perspective hugeness, while every instrument on the orchestral soundtrack goes on a berserker rampage in search of a tune. A slashed hand births stars. A blood-meridian sun sets. A lizard turns into a woman. Suddenly, though, the gorgeous, garish assault of image and sound gets slow, goes quiet. The woman, naked and basking, is observed by the man, lying not far away. He tucks an elbow under his head as sand blows in around them—perhaps the sands of time itself—and keeps blowing, collecting in billows and drifts against the two figures until soon they, too, are sand, briefly solid, briefly stone, before being eroded to weathered sphinxes, then less, their bodies just contours, then not even that, sad little hillocks of dust scudding away to nothing. If only Dr. Edward Jessup (William Hurt) were paying closer attention to his hard-won hallucinations, halfway up this Mexican mountain, halfway through this trippy tribal ritual, he might see that all he’ll ever learn on his fantastic voyages into the uncharted depths of the collective unconscious is contained here, in this scene playing out behind his dilated pupils, this atypically sincere little hymn to human transience within the phantasmagoric eternal. But then he wouldn’t continue his experiments. And we wouldn’t have the dippy, delirious Rube Goldberg machine that is Altered States.

Ken Russell’s 1980 film is gleefully baroque, as befits the sensibilities of its director, yet the story is simple, as dictated by the declarative, “mad as hell” impulses of screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky, of Network fame. Eddie Jessup is a respected psychopathologist who comes to believe that, by ingesting a powerful hallucinogen while in an isolation tank, he can access aspects of the human condition that have lain dormant since prehistory. Much to the consternation of his reluctant accomplices, scientists Arthur Rosenberg (Bob Balaban) and Mason Parrish (Charles Haid), he is proved correct, even at one point physically transforming into a simian protohuman (played by dancer Miguel Godreau in a grotesquely convincing full-body hair suit courtesy of makeup maven Dick Smith). But soon, the transformations and deformations are occurring unprompted, which is especially disturbing to Eddie’s wife, Emily (Blair Brown), a brilliant anthropologist who, despite keeping company with this cadre of geniuses, often seems like the only one in the room with a lick of sense.

Because as much as Altered States, through Jessup, searches for some singular, irreducible truth that will make all the chaos and suffering of existence meaningful, it is also about the sheer hubris of such an ambition, the grandiose—and here, very masculine—folly of it all. As directed by indefatigable enfant terrible Russell, who treats the gustier passages of Chayefsky’s screenplay with a giddy disdain that drove Chayefsky up the wall and off the project (and, some say, even hastened his death at fifty-eight, mere months after Altered States was released), the resultant movie walks a tightrope between pretentious self-seriousness and outrageous flippancy. It is hard to conceive of a film more dazzlingly, dizzyingly divided against itself—or one more appropriately so—than Altered States.