Flow: Swept Away

The history of animation is partly a history of representing animals on-screen. The camera loves them: the harmonious forest fauna of early Disney, the wisecrackers of Looney Tunes, the metaphorical creatures of Soviet animation, the kid-friendly heroes of later Disney, Pixar’s tidy bright-eyed critters, the haunting beasts of Hayao Miyazaki, the uncanny valleys of photorealistic animation, and let’s not even start on the reanimator eeriness of stop-motion. Animal movement is a building block in the very lineage of the moving image, thanks to Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic studies of horses running. Animation’s latest animal triumph, Flow (2024), has the fidelity of a behavioral study partly because it’s dialogue-free, or—to be more precise about a movie full of meows and barks and grunts and squawks—free of human speech. Gints Zilbalodis’s beguiling vision, at once post–video game and grounded in millennia-old humanism, goes beyond staging four-footed derring-do to induce quite profound meditations on consciousness and identification.

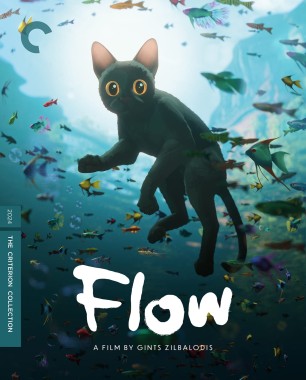

That’s not to say Zilbalodis isn’t working with some fundamentals of mass entertainment: Flow is many things, but in bare outline it’s a tale of an animal in peril. We begin in an unexplained, unidentified land that is verdant and outwardly serene yet deserted by humanity. It’s like the cold open of a multiplayer game or a virtual-reality demonstration, replete with abandoned realms to explore, starting with an empty bungalow that looks like an artist’s workshop, its surroundings dotted with statues of cats—perhaps once in tribute, but now bespeaking absence. But this won’t be a mere travelogue of desolation. Zilbalodis opens with a visual motif that will haunt the film: a reflection of a dark-gray cat looking at itself in the water. It’s at once an introduction to the film’s protagonist and a defining keynote of communion for the viewer—this isn’t quite the first person, but we are definitely with the cat in spirit.

It’s a fearful place to be, since the first act of Flow cranks into gear with a disaster movie’s rush of action, hurtling the cat from lazy days of roaming and resting into a scramble for survival. The nameless feline’s seemingly solitary existence is upended, newly requiring cooperation with (or at least tolerance of) others to escape and survive a biblical-scale flood that obscures all that is recognizable about the patch of earth the cat has called home. In succession, Zilbalodis trickles in new animal characters—dogs, a capybara, a lemur, a towering secretary bird—each of which first lights up the cat’s threat matrix before posing more manageable challenges of cohabitation.

After the disaster movie comes a sort of road movie, but on a boat, gliding past submerged trees and unpredictable protruding ruins: a busted stone hut where the lemur tends to a collection of bric-a-brac, or the outstretched hand of a human statue, a soft jump scare as it suddenly enters the frame. In another echo of video games, particularly of the postapocalyptic variety, larger signs of vanished civilizations heave into view: a sandstone city turned Venetian with canals, glimpses of Mayan-like remnants, a fleet of rowboats dashed against stone pillars, a Greek amphitheater, and left-behind baubles of people who never said farewell. A postcollapse palimpsest, yet somehow without doom, a bit like the international pastiches in Miyazaki, whose early-career TV series Future Boy Conan has been cited by Zilbalodis as an influence.