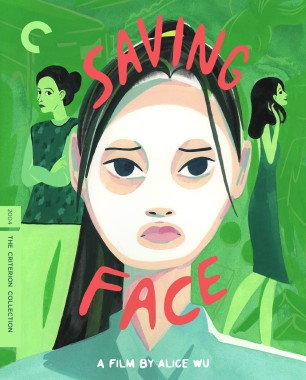

Saving Face: Daughters in Love

To propose a variation on the adage: All good daughters are alike; each bad daughter is disappointing in her own way. In Alice Wu’s debut film, Saving Face (2004), one bad daughter finds herself pregnant out of wedlock, trailed by gossip and subject to shaming even at her perimenopausal age. Another—her own daughter—is a young surgical resident, so gifted we hear talk of her precocity before we learn her name, Wilhelmina, though she has shed its lilting syllables for the neutral and unshowy Wil. Wil (Michelle Krusiec) generally tilts toward self-effacement, defaulting to the easy androgyny of button-downs and sensible shoes. She rides the Manhattan-bound B train to work in the blushing dawn and assists with reconstructive surgeries in the operating room, but she cannot shake the sense of badness that clings to her like a shadow.

As with many daughters, Wil’s guilt keeps her tied to a performance of being good. She heads into Flushing, Queens, on Friday nights to join her mother and grandparents at the Chinese community dance. The collective stage of the banquet hall has its own demarcations, like the hidden cartography of a high-school cafeteria. The dance floor is all nervous pursuit and flirtation. At its nearest edge, a row of aunties stand with their buffet-heaped paper plates, women in big jewels and little heels who recur in montages throughout the film, gossiping, tossing wry remarks here and there. Opposite them, bespectacled uncles in bow ties are chowing down and engaging in the same. Such is the texture of intimacy in this multigenerational community; there’s warmth to the nosiness, being caught up in each other’s business.

At the dances, Wil tends to the pretense of her heterosexuality—to ease the guilt of her queerness—as one might a low-commitment houseplant: just enough to keep it alive. She dances dutifully with whichever young bachelor Ma flings her way, wishing she were anywhere else. One night, however, Wil spies a vision in gray silk on the mezzanine, and when she doubles back for another glance, the sheer eagerness in her look is enough to be a confession. From that point on, she has eyes only for Vivian (Lynn Chen), the forthcoming femme in silk. A dancer, Vivian is at ease in her body and her own queerness. Chinese American girl meets girl: a rom-com hook almost as unlikely now as it was on the film’s initial release. Saving Face has generally been labeled a rom-com, and the tropes of that genre abound, from the dance-floor meet-cute to the denouement of a go-get-your-girl airport chase. But it’s a lamplit seduction scene that best conveys the push-pull dynamic of Wil and Vivian’s romance. In the sultry glow of her apartment one evening, Vivian shows Wil how to perform a stage fall: let your arms swan open and your body unfurl, joint by joint. Wil is a clenched fist, awkward and unable to let go—until Vivian leans in, so close that their faces almost touch. Wil panics, dodging the kiss by collapsing to the floor in a sudden, ridiculous crash, brought to her knees not by desire but the fear of it.