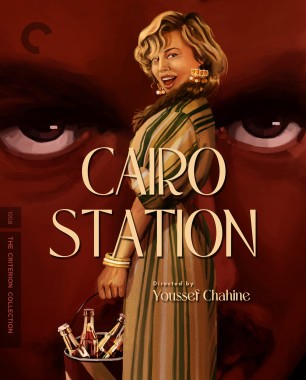

Cairo Station: Of Time and the City

For over half a century, Egyptian film has been largely synonymous with the name Youssef Chahine—the most internationally recognizable Egyptian auteur, whose boundlessly inventive popular cinema spanned six decades, from the 1950s through the 2000s, earning numberless accolades around the world, crowned by a lifetime-achievement award at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival. In his home country, Chahine was always a divisive figure. Yet for every Egyptian with even a faint interest in film or art, engaging with Chahine’s work remains a rite of passage. A cultural and political icon, Chahine for some Egyptians was the supreme entertainer, the shrewd agitator, the peerless craftsman, the towering national treasure. For others, he was the public enemy, the brazen renegade, the degenerate Westernized charlatan.

Emerging in the early fifties, during the golden age of Egyptian cinema, Chahine immediately revealed himself to be a highly confident artist with a talent for infusing standard Hollywood-style entertainments with an unmistakably Egyptian spirit. Later that decade and throughout the sixties, he experimented more radically with Western genres—Italian neorealism, sociological noir, historical epic—creating hybrid films unique for their striking Egyptian iconography and socialist-leaning themes. These works cemented his reputation as one of the most authentic, creative voices in Arab cinema, a status he maintained for the rest of his career—even when he ventured into more politically confrontational films in the seventies, before moving inward, tackling autobiographical and existential concerns in the eighties, and then outward again, with his hugely popular epics at the turn of the century. In 2007, Chaos, This Is—which anticipated the 2011 revolution—showed that the eighty-one-year-old director, a vocal member of the political opposition, was continuing to fight until his very last breath.

Cairo Station (1958), which epitomizes his late-fifties hybrid style, is central to the Chahine myth: a masterpiece that was nonetheless a box-office disaster, nearly ending the filmmaker’s career prematurely. A remarkably sensitive yet jarringly violent unrequited romance, fronted by a disabled, sexually frustrated worker driven to murder, the film was released amid a period of exultation in Egypt, following the fall of the monarchy; the emergence of Egypt as a republic and a leader of African decolonization; and the 1956 defeat of Britain, France, and Israel by President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the Suez Crisis—an epoch of contagious optimism marked by extensive industrialization and a sweeping cultural revival.

Chahine’s film was an anomaly among the safer melodramas of the era, however: a damning psychological study of a marginalized class left out by the revolution. Contemporary Egyptian audiences expected their fatalistic melodramas to encompass a moral message, no matter how forced or contrived. Cairo Station contained none: it was too deviant, too dour, too cruel, too morally ambiguous. And it was roundly rejected by audiences (if not by critics), disappearing from public consciousness for almost two decades before it was broadcast on television in the seventies and belatedly embraced.