Zwerin works in some earlier material, too, like Monk’s 1957 appearance on the CBS television series The Seven Lively Arts. A shot angled over Monk’s shoulder shows Count Basie at the other end of the piano, watching Monk play with a bemused look on his face that seems to say “Can you believe this guy?” (though who knows, maybe he’s just digging the playing). Basie also may have been distracted by the derby hat and shades, the encumbrances of Monk’s public image as a Beat weirdo, the whole Guru Sphinx of Bop mythos. Yet all this evaporates through simple attention to Monk’s real-time invention at the keyboard, as he tosses out idea after idea after idea. Whatever the content of Basie’s expression, it irked Monk, who later told his manager that next time Basie played, he was going to “sit across the piano and stare at him the whole time.”

There is also footage from 1958 of Monk’s quartet at the Five Spot bar on Cooper Square in New York (excerpts from these dates can be heard on the Riverside releases Thelonious in Action and Misterioso). After a 1951 drug bust in which Monk refused to rat on his friend Bud Powell (and thus having to spend a couple of months on Rikers Island), Monk’s cabaret card had been revoked, which meant he could no longer play in clubs that served alcohol. Six years later, he was able to return to the clubs, beginning with the Five Spot; the charged exuberance in the playing we see from a year later seems to still be partaking of the momentum of being back (an effect likely enhanced by John Coltrane being in the band at the time). Shots from the Five Spot show an all-white, faintly bohemian crowd, smoking and smiling—amused, perhaps, by Monk’s aura of oddity—in any case thrilled to be taking in what was then certainly the cutting edge of downtown music in New York City.

As a counterpoint to the archival material, Zwerin shot new footage of pianists Tommy Flanagan and Barry Harris (both Detroit natives, like Zwerin) playing through Monk tunes as four-hand duets. We see how much fun they’re having, how generous and congenial their sharing of the music is, and how a Monk song like “Well, You Needn’t” allows for endless elaboration without its melodic outline ever becoming blurred. Later, Flanagan and Harris play a slow-tempo “Misterioso,” and Zwerin sets it under a shot of Monk staring expressionlessly at a scrap of sheet music, bringing out the eeriness of the tune as it becomes a gloss on the inaccessibility of Monk’s inner life.

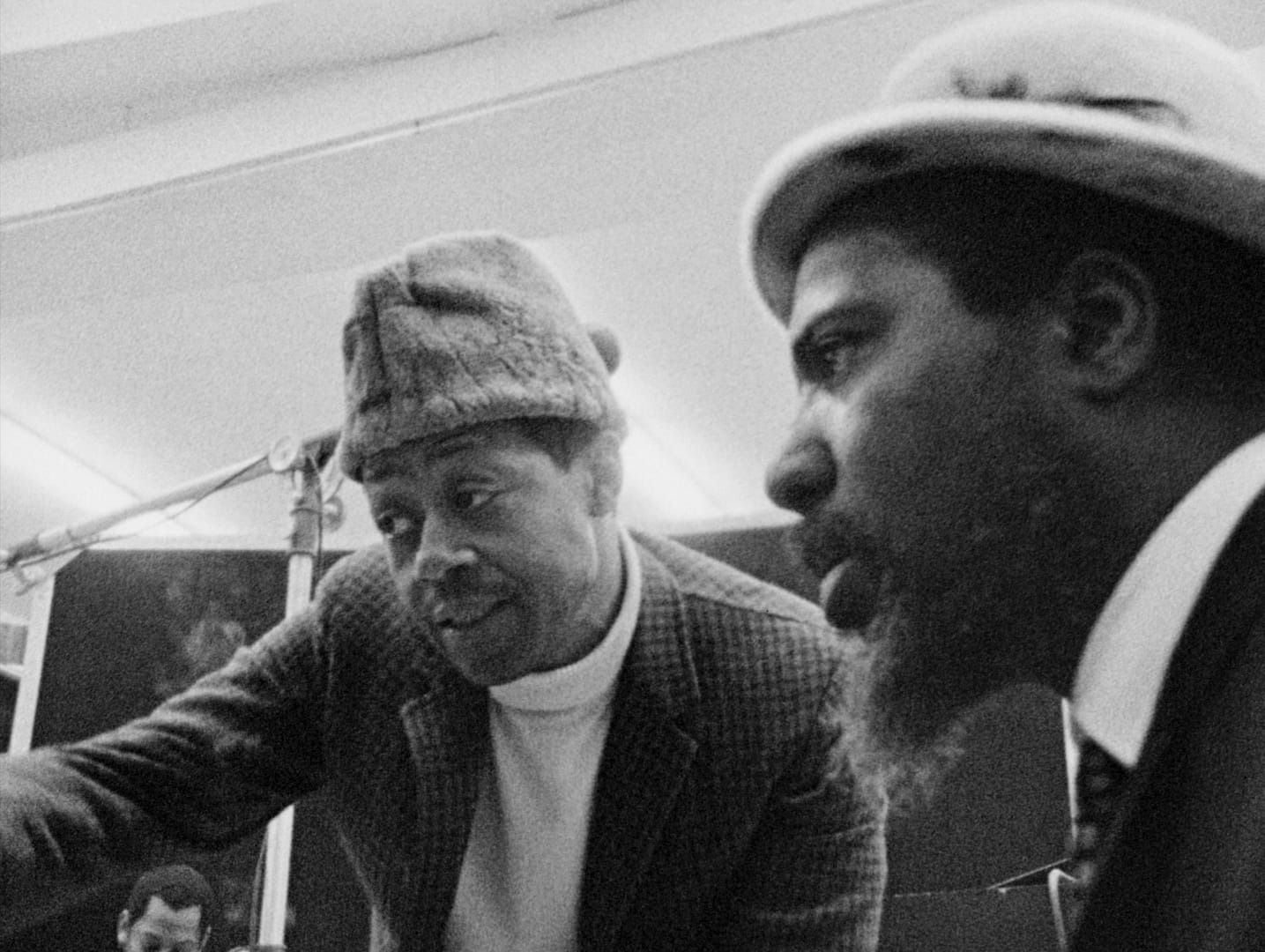

The Blackwood footage includes Monk and his band visiting the legendary Columbia studio on East Thirtieth Street, which had been an abandoned church before the record company converted it in 1948. “The Church,” with its fifty-foot ceilings and incomparable acoustics, was where everything from the original Broadway cast recording of West Side Story to Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, Igor Stravinsky conducting his own The Rite of Spring, essentially all of Tony Bennett’s records, and Frank Sinatra’s “Theme from New York, New York” were recorded. Monk arrives in a tweed topcoat, some kind of rhombus-shaped beret, white leather gloves, and scholarly-looking glasses that turn out to have no lenses. When producer Teo Macero comes out to greet him (while doing hammy impressions of Monk-style dance moves), he starts cracking up about Monk’s “jive” spectacles.

Macero, an accomplished saxophonist who produced and arranged hundreds of recordings in every genre, had been instrumental in getting Columbia’s jazz roster together (including Dave Brubeck’s 1959 crossover smash “Take Five”). He would later preside over Davis’s In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, thus ushering jazz from its still acoustic post-bop abstractions into its parapsychedelic electric period, much to the chagrin of various traditionalists. During the sessions with Macero (which ended up on the 1968 Columbia release Underground) we get glimpses of Monk’s irritability. After running through a new piece (“Ugly Beauty”), Macero checks in from the control room, saying, “Okay, Monk, let’s really do one now,” to which Monk replies, “What? Why did you stop us?” When it happens again, Monk balls up his fists and complains, “Why will nobody do what I ask them to do?!” Macero tries to cool things down by saying that it’s good to do a few rehearsals first; Monk replies aloofly: “You rehearse every time you play on your instrument. You should know that.” The tone is of an artist who demands control over the proceedings, and a reminder that willfulness, even petulance, are qualities of temperament sometimes found in the neighborhood of genius.

There’s some footage of Monk doing his “spin” dances in the stairwell of the Village Vanguard, while his friend, patron, and occasional caretaker the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter (for whom Monk wrote the gorgeous ballad “Pannonica”) sits on the stairs behind him, after which Monk says, apparently ventriloquizing one or another of the myths about his eccentricity, “Oh, that Thelonious Monk, he’s crazy.” What ultimately was the nature of this “craziness,” what was behind the increasingly frequent bouts of mania followed by near catatonia, is unclear without some exercise in anachronistic diagnosis. “It’s hard to say exactly [how these episodes] moved,” his son, Thelonious Jr., says in one of the interviews conducted for the film. “It was very complex; he was a very complex individual.” From Monk’s longtime manager, Harry Colomby, we learn that one of these periods of total withdrawal seemed to be manifesting in the summer of 1963, at the time of Monk’s first meeting with a Time magazine writer assigned to do a cover story on bebop; Colomby worried that this major publicity coup would be derailed. But Monk did appear on the cover of the February 28, 1964, issue of Time and indeed had, late in life, the gratifying experience of fame. Some of the Blackwood footage shows Monk walking around Sixty-Fourth and Amsterdam with strangers calling out to him on the street.

Later footage shows Monk looking gaunt, playing with staggering beauty through his song “Crepuscule with Nellie,” written for his wife. Nellie looked after every aspect of Monk’s life, and throughout the Blackwood footage we see her tending to him in hotel rooms, in airports, on airplanes, telling him what clothes to wear, where to find his things, where to go, making sure he has money in his pocket. “He would be lost without her,” Monk’s bandmate Charlie Rouse tells us. The biggest grin we get from Monk in the whole movie is when he’s sitting with Nellie on a flight to London for a run of performances.