From 1940 to 1970, the Black population of Los Angeles grew many times over. Most new residents arrived from the South, part of the Great Migration’s second wave. Lured by a stateside expansion of industry during World War II, thousands of strivers left the old country for far-west cities like San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, and LA. Many came fleeing dwindling job prospects in the agrarian lowlands or the tyranny of the Southern mob. Still more came for the opportunity to buy property: word had gotten around that, since the earliest decades of the century, LA had among the highest rates of African American homeownership in the continental United States.

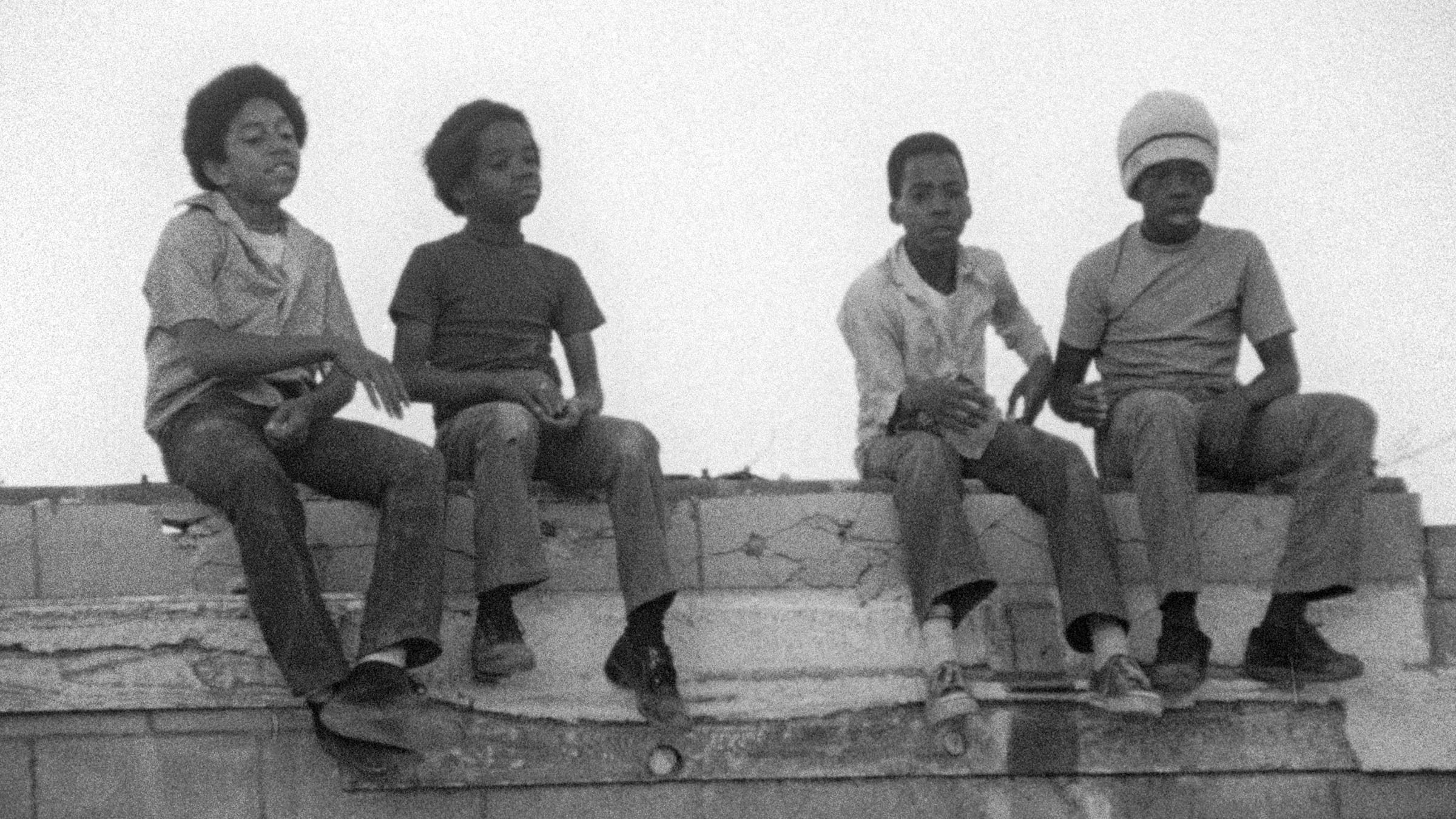

Burnett was born in 1944 in Vicksburg, Mississippi, an old Confederate port that marks the southernmost point of the silt-rich Delta—the birthplace of the blues as we know it. He moved to LA with his family when he was “barely walking,” he recalled. New residents brought their sounds and swagger and storytelling traditions to the new milieu: “Everyone was from the South,” Burnett said. “So you had this Southern environment there . . . Also there was that jazz influence—we had to be cool, had to walk a certain way.”

In Killer of Sheep, characters reference “back home” in contradictory ways. Sometimes, it represents revelry: little boys playing by the railroad joke about visiting the “Vicksburg Club” to watch the ladies of the night pass by. Other times the South is something to long for. Played by Kaycee Moore like a flower that blooms and wilts depending on the mood, Stan’s wife (unnamed in the film) experiences her husband as cold and withholding. The weight of his job and his responsibilities seems to alienate him from his own tenderness. After one disappointing encounter with him, she remembers warmth from miles away and years ago: “Memories that just don’t seem mine, like half-eaten cake, rabbit skin stretched on the backyard fences, my grandma . . . dragging her shadow across the porch, standing bareheaded under the sun.”

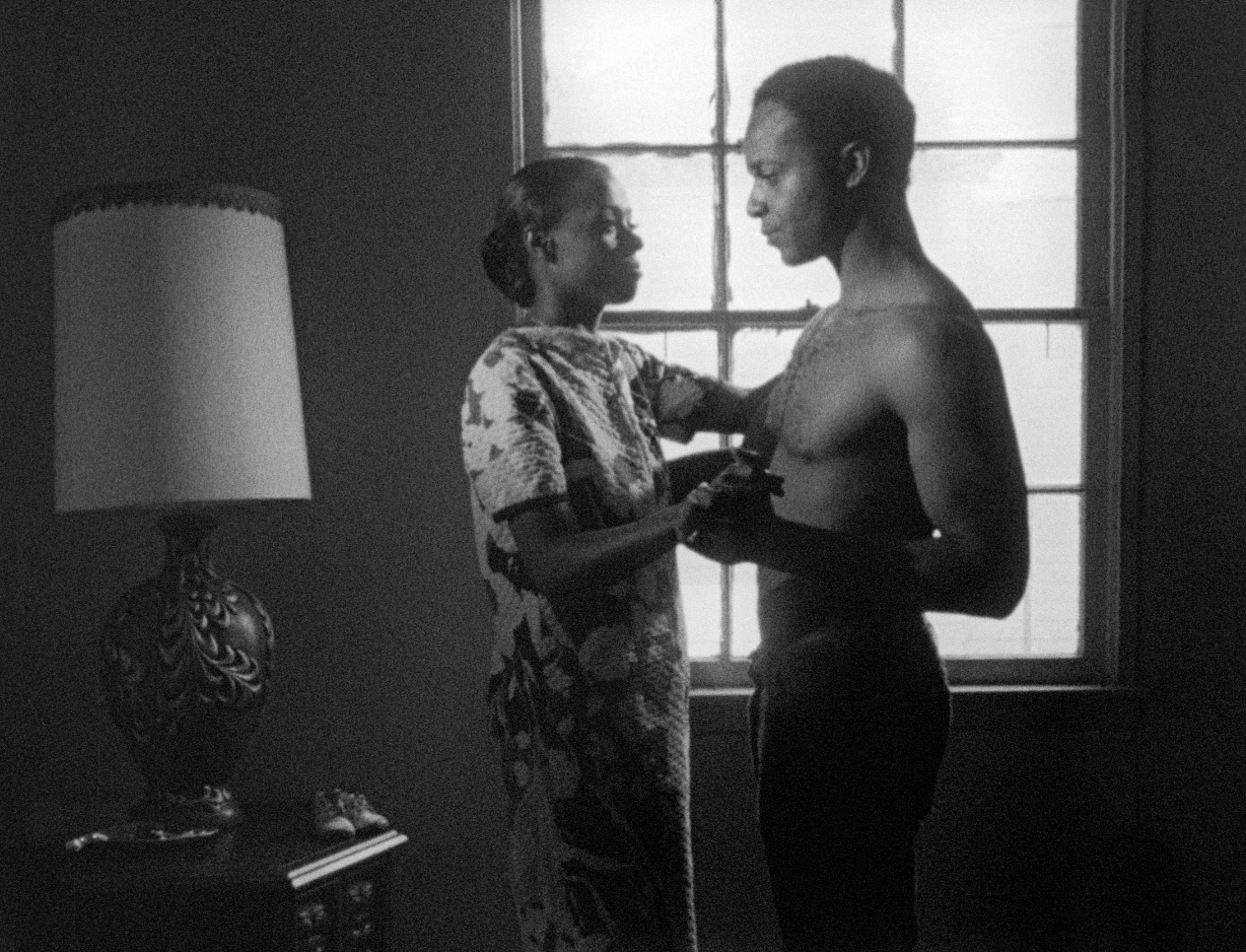

Her yearning, to be seen and tended to, is also for a place where she can live in intimate relationship to the land. Her longing for home is a good sign: her heart is still accessible; she still possesses the ability to yearn. In contrast, Stan scolds his son for calling Moore’s character “Mudeah.” The traditional Southern portmanteau for “Mother dear” usually connotes respect. “How many times I tell you don’t call your mother ‘Mudeah’? You ain’t in the country or something.” Stan works and lives so his family can prosper and progress; country ways should be behind them. But progress comes slow, and its costs are heavy.

The conflict between old ways and newness plays out in intricate moments and interior questioning made concrete. In a film that is driven less by plot than by poetic reverie, the inner turmoil of each character must surface in gesture, on the face. So Stan, played magisterially by Henry Gayle Sanders, often wears a puzzled look. A tight anxiety shoots through his limbs; malaise seems to emanate from his skin. He is caught—close enough to providing well for his family that he can see it; far enough to feel shame for the way he must provide that living, and for the limits of his provision. He’s also courtly and loving with his neighbors, all fellow strivers he regards with knowing and respect. The rare moments in which he finds ease, the feeling is a gentle burst across his entire face.

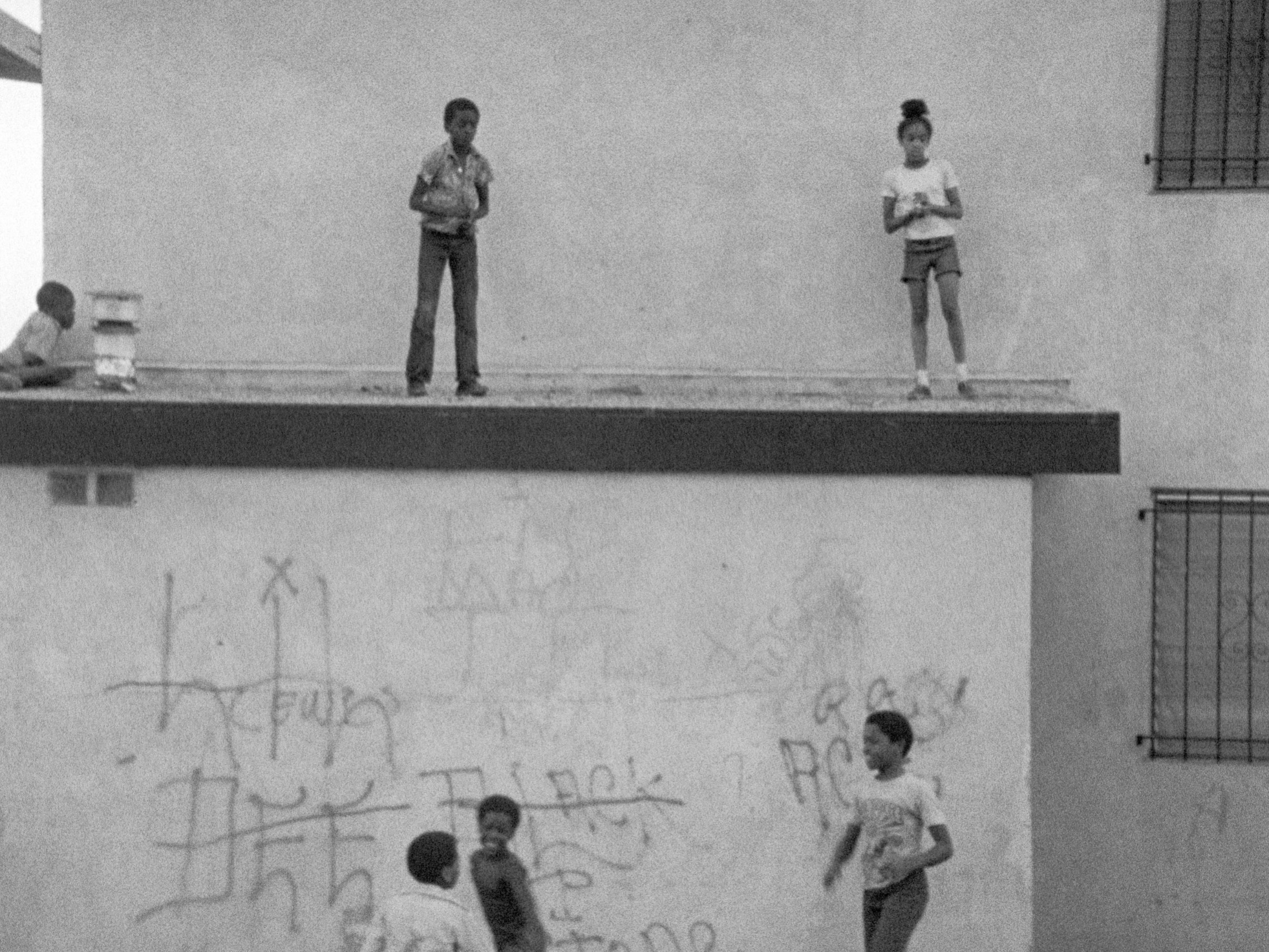

Killer of Sheep was Burnett’s thesis film at UCLA, where he earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees. From one of his instructors, Basil Wright, Burnett learned to “keep focus” on who he was “making the film for,” he has said. So Burnett decided, as a student, to depict his community on camera “with dignity,” to “show what was true to Black life.” Other students were on a similar mission—and also shared a strong desire to subvert Hollywood’s traditional structures and stereotypical depictions. Burnett and his fellow filmmakers, eventually deemed the LA Rebellion by scholar Clyde Taylor, were preoccupied with interiority and careful specificity. They took influence from cinemas in West Africa and South Asia, and from the old “race” films of the twenties, thirties, and forties, made for Black audiences by Black filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux. The LA Rebellion directors Larry Clark, Haile Gerima, Billy Woodberry, Bernard Nicolas, and Julie Dash had differing, overlapping tenures at UCLA. For one another, though, they doled out advice over long conversations in the student lounge. Like a collective of players of jazz or the blues, they often worked on one another’s films, switching instruments (cinematography, or acting, or writing) when appropriate.

The critical and word-of-mouth success of Killer of Sheep assured that Burnett would continue working as a filmmaker. In features such as My Brother’s Wedding (1983) and To Sleep with Anger (1990), he carried on his interest in masculinity, Black folkways, and West Coast transplants from the American South. Music has also remained a vital part of his work, as in his dreamlike episode of Martin Scorsese’s 2003 PBS series The Blues. “Ain’t but one kinda blues,” the Delta bluesman Son House says in an interview excerpted in the episode. “And that consists between male and female that’s in love.”

In an essay on Killer of Sheep, music critic Nate Patrin wonders: “Can a film be blues?” Burnett’s movie shows, virtuosically, that it is indeed possible. The film’s score alone could be sufficient proof. Drawing from the entire musical history of Black America, Burnett placed traditional spirituals alongside country blues, urban blues, early jazz, and hip seventies funk. Paul Robeson flows into William Grant Still; Little Walter sings beside Scott Joplin’s keys; Faye Adams and Louis Armstrong ground Stan’s striving—at work and at home. The magnificent and the mundane are one and the same.