This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection: Staying Power

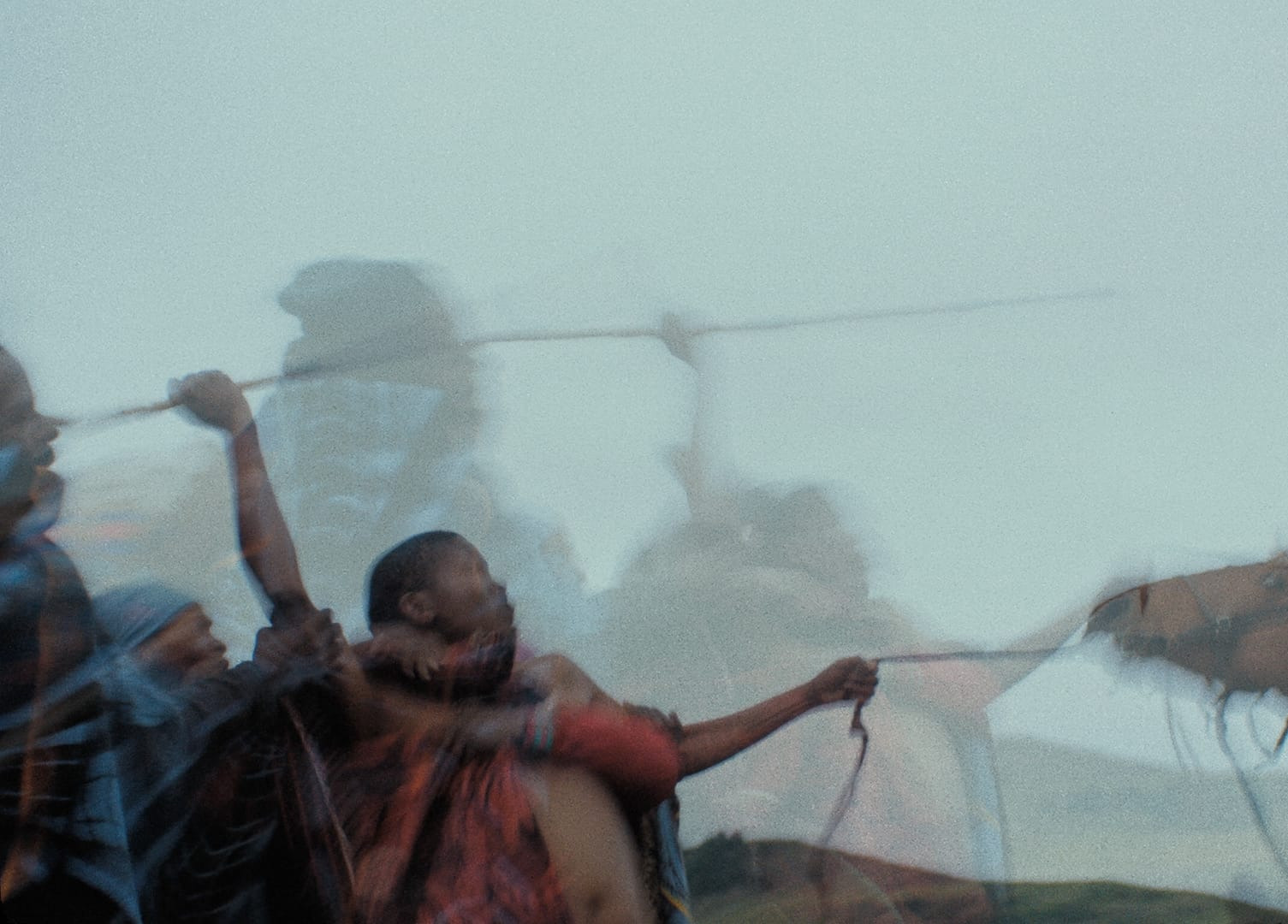

The story of Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese’s This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (2020) unfolds through poetry. The poetry of images and words—the interplay of light and shadow, and the lyricism of the narration. It ensnares us right from the opening shots, of a horse going through an aesthetically beautiful yet obviously traumatic experience at the hands of blanketed Basotho men and women. The action is made more haunting by the application of a Wong Kar Wai–esque step-printing technique—which blurs and then sharpens and then smears the image over the excitement of the perpetrators and the resistance of the victim.

The film is set and was filmed in Lesotho, a former British protectorate that is now an independent kingdom, which is geographically completely surrounded by South Africa and therefore highly dependent on South African goods and services. A great percentage of Lesotho citizens work in the mines, farms, and homes of South Africa, and Lesotho also relies heavily on their remittances. For its part, however, South Africa needs the water that is piped to it from Lesotho, where huge dams have been constructed. Many Lesotho villages have been displaced to make way for the construction of these dams. At the heart of This Is Not a Burial is just such a displacement. The story focuses on the bereft eighty-year-old widow Mantoa, an accidental hero who finds herself becoming a catalyst for her community’s resilience.

The setting of the film’s opening is bleak. We are in a run-down tavern. The notes of a lone lesiba instrument fill the air—if we can talk of air in this environment, which looks stuffy despite the fact that the space is sparsely populated, its denizens all sitting or standing by themselves, each perhaps contemplating the social pain caused by a lack of connection with others, each body weighed down by loneliness at worst, solitude at best. Perhaps we’ll learn which as the movie proceeds. Loneliness is imposed on one; solitude is a choice. Solitude is the state of being alone without being lonely.

Solitude is also the stuff of magical-realist fiction. And This Is Not a Burial has strong elements of that narrative mode, not because it exudes a sense of the supernatural but because, in it, the strange and the unusual exist in the same context as objective reality, without being disconcerting. For example, in one scene, as Mantoa (Mary Twala Mhlongo, who was seventy-nine years old at the time of shooting) sits among the ashes and debris of her burned-down house, a group of sheep appears, and the animals rally around her, giving her solace.