A Story from Chikamatsu: From a Distance

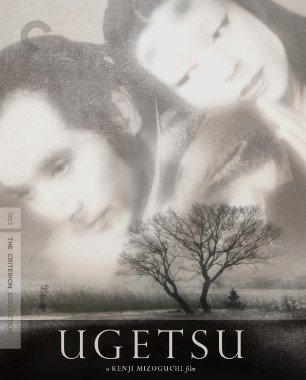

A crucial film from the remarkable final phase of Kenji Mizoguchi’s prolific career, A Story from Chikamatsu (1954) has long been overshadowed by the director’s best-known works from the same period: The Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), and Sansho the Bailiff (1954). Winners each of major prizes at the Venice Film Festival, those three have been canonized as a loose trilogy and together celebrated as the apogee of Mizoguchi’s mature filmmaking. Although less recognized today, A Story from Chikamatsu is an equally significant masterwork that gives important new dimension to the formal and genre innovations for which the trilogy is renowned—the lyrically measured cinematography and inventive approach to adaptation guiding the transformation of canonical works of literature into spiritually charged and politically trenchant jidai-geki, period films set in Japan’s feudal era, that also embrace elements of the socially conscious melodrama first explored by Mizoguchi during the 1930s.

Like the films of the trilogy, A Story from Chikamatsu renders a harshly critical portrait of Japan’s past, in this case a dark vision of Tokugawa-era Kyoto as a venal, petty, and paranoid society thoroughly corrupted by a blind obsession with wealth and social status. The film’s tragic story of doomed lovers separated by class and marriage, a dutiful artisan apprentice and his master’s younger wife, is thus driven forward by a quick series of cruel betrayals and overzealous punishments exposing the deep instability of life within a near police state whose citizens’ actions and morals are under constant surveillance and whose subjects—women in particular—are treated as commodities to be bartered and exploited. This focus on the lives of oppressed women also revives and reinvents the mode of melodrama pioneered two decades earlier by Mizoguchi and screenwriter Yoshikata Yoda in their breakthrough collaborations Sisters of the Gion and Osaka Elegy (both 1936), paired gendai-geki—dramas set in the present day—that form a diptych portrait of women whose failed struggle for independence tragically results in destitute lives of bitter servitude.

In the fifties, Mizoguchi and Yoda dramatically expanded the scope and vision of their political melodrama in an ambitious span of films, alternating between the evocative jidai-geki embodied by the trilogy and A Story from Chikamatsu and a group of daring, psychoanalytically inflected gendai-geki centered on strong-willed yet ultimately victimized women, such as Miss Oyu (1951), A Geisha (1953), and The Woman of the Rumor (1954). By focusing on tragic stories of class inequity and victimized women, this thematically intertwined series of films drew dark parallels between Japan’s feudal past and present day and offered a subtle meditation upon history and its legacies during a troubled period of postwar recovery when such gestures remained quite controversial. In this way, the films pondered the vexing question, asked repeatedly by artists and policy makers alike across the period following Japan’s defeat, of how to understand the zeitgeist and mind-set that had so perilously brought the nation to war, and how, moreover, to address lingering cultural and ideological continuities between the pre- and postwar periods.