The Lure: One Is Silver and the Other Gold

At the heart of The Lure are a couple of questions: What is a girl when she is not yet a woman? What about when she is also a fish—and she craves the taste of human hearts? Over the course of this 2015 debut film, a mermaid musical-horror-fantasy, the Polish director Agnieszka Smoczyńska dives deep into dark waters to explore these riddles, crafting a meditation on innocence, violence, family dynamics, sexual exploitation, and feminine nature.

The film is a loose adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” a fairy tale with a message to girls so daft and damaging it’s hard to picture a woman as ferocious as Smoczyńska choosing it for any reason other than to turn the story on its head and settle old scores. In Andersen’s tale, a young mermaid sacrifices both her voice and her life in the sea in an effort to win the love of an unworthy prince and, with it, an immortal human soul. She works tirelessly to seduce him, even while every step she takes on her new legs feels like walking on knives. In return, the prince treats her like a pet, making her sleep at the foot of his bed, and then marries another woman, sentencing our heroine to death by transformation into sea foam. But the Little Mermaid, thanks to her sisters, is granted a reprieve from this fate: the chance to murder her abusive prince in exchange for her own life. Instead, she chooses to sacrifice herself. Rather than achieving the sweet relief of frothy oblivion, however, she finds she has become one of the “daughters of the air.” The other daughters remind her, “A mermaid has not an immortal soul, nor can she obtain one unless she wins the love of a human being. On the power of another hangs her eternal destiny.” Her new duties include three hundred years of flying around and fanning men when they get too hot. And as if that weren’t bad enough, any time children are naughty, her sentence is extended.

The Lure, inspired in part by Warsaw’s mascot of a sword-wielding mermaid, a fighter who just happens to be beautiful, douses the pages of Andersen’s timid tale with kerosene and sets them on fire, recasting the heroine as two teenage sister mermaids and giving them back their voices, their agency, and their teeth. They rise from the sea singing (Smoczyńska was also inspired by Homer’s deadly sirens) and fully in possession of their otherworldly power over human males. They come ashore innocent of the idea that ours is considered a man’s world. They move through it at first as though it belongs entirely to them and anything they want will be theirs.

Screenwriter Robert Bolesto wanted to make a movie based on the lives of his friends Barbara and Zuzanna Wrońskie—who spent their childhoods in nightclubs with their performing parents—with an eighties-inspired electro soundtrack by the sisters’ band, Ballady i Romanse. Bolesto brought his script to Smoczyńska, who herself grew up in Soviet-era “dancing restaurants” managed by her mother. When one of the sisters started feeling that the project was too intensely personal, the writer and director decided to turn the main characters into mermaids, and to add the devouring of people to their talents of singing and dancing. The resulting film, with its wildly original soundtrack that glides from wistful ballads to disco to show tunes to Europop to punk, is a colorful, exuberant, and absurdist genre experiment that introduces a distinctive new directorial sensibility in Smoczyńska. You can practically taste the salt water—and the blood.

The opening credit sequence is an animation by the painter Aleksandra Waliszewska, known for her nightmare-inducing takes on fairy-tale characters—our first indication that we are in waters far from Disney. Skulls bob around the mermaid sisters as they swim sinuously about their aquatic serial killers’ den, their sweet singing voices and long gold and raven locks in stark contrast to their grim surroundings.

The animation dissolves to live action, and Silver (Marta Mazurek) and Golden (Michalina Olszańska) surface near the shore, drawn by the gentle singing and guitar strumming of Mietek (Jakub Gierszał). The sisters watch with interest, then return his serenade with their own siren song, an assurance that no one will be eaten for helping them ashore—though their eyes tell a different story. Nevertheless, Mietek and an older man whom the film refers to only as Perkusista, or “drummer” (Andrzej Konopka), reach out to assist the girls. And then we meet the third member of this ad hoc musical family, singer Krysia (Kinga Preis), who stops her drunken dancing on the beach and lets out a scream as, presumably, the humans see the mermaids’ spectacular tails for the first time.

Her scream transforms into song on the film’s soundtrack as Krysia, dressed to slay and wiggling onstage at a 1980s Warsaw nightclub, coos Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” (these scenes were shot at the Adria, a real-life club in which the Wrońskie sisters’ parents had performed). The club owner searches for the source of a mysterious fishy odor and discovers the girls in the dressing room, dancing and playing like children. Krysia’s partner, the percussionist, instructs the sisters to disrobe and shows his boss that their genitals are nonexistent, “smooth as Barbie dolls,” then demonstrates how water turns them back into mermaids. Smoczyńska has created aquatic angels on the cusp of womanhood—the girls’ transformation into mermaids hangs heavily over the film as a metaphor for female puberty, with all the attraction and repulsion, the odor and slime, that come with it, along with its threatening power over men. The sisters are often naked, at first unselfconscious in a childlike way, then aware of the magnetism of their bodies. The nightclub boss hires them to strip, sing, and occasionally flash those tantalizing tails. The appendages, designed by Waliszewska, were nearly seven-foot-long practical models that the actors wore and operated with pedals (though some CGI was also used). They worked with a choreographer before the shoot, learning how to move in the tails, and the results are incredibly realistic and eerily beautiful.

The sisters settle into their new life, learning how to navigate the dysfunctional family dynamics of the three musicians, whose cramped apartment adjacent to the nightclub they now share. Krysia positions herself as a mother figure to the mermaid girls, both onstage and at home—a situation that ultimately will serve no one, as the aquatic adoptees begin to send ripples through the formerly smooth seas of the trio’s domestic life. Silver and Golden’s act becomes the toast of Warsaw, and they decide (communicating, via their unique brand of telepathy, in seventeen-layer, dolphinlike voices) to put off their plan of swimming to America. As they put it in a lavish musical number set in a mall, “I’m new to the city / I wanted to put my best foot forward / Change what I can change and get their attention / A mention, a nod . . . The city will tell us what it is we lack!” They are like newly arrived immigrants: ignorant of the local customs, eager to explore, easily exploited. And the unfamiliar world they find themselves in appears to them much like the nightclub itself: sometimes enchanting and dazzling, sometimes dark and punishing.

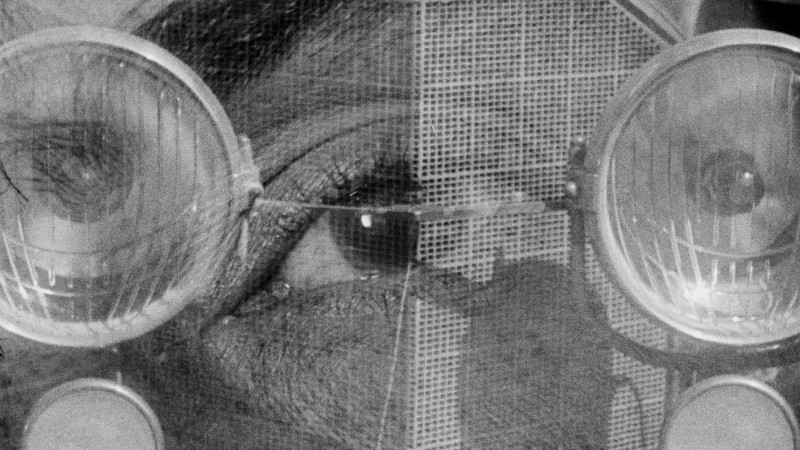

Production on The Lure took only a month, although Smoczyńska and the two lead actors had an intensive rehearsal process beforehand, learning to trust one another, creating backstories for the characters, spending time getting into their psychologies as well as their physicalities—what it would feel like to be part animal, part human; to walk on legs for the first time; to be a predator. The resulting performances are remarkably unrestrained. Adding to the immediacy is the fact that the cast all performed their own vocals for the musical numbers live during filming. The naturalness of the acting is set against the psychedelic refracted neon of the pulsating nightclub world and the light-shot underwater gloom of many of the musical numbers (embedded in production design by Joanna Macha), to delirious effect. Smoczyńska exquisitely conveys the emotional reality of the sisters’ sometimes brutal initiation into this world—the first drink, the first cigarette, the first love, the first sexual encounter—as well as how intensely these kinds of experiences can be shaped by music.

Everything is going well until Silver begins to fall for Mietek. He appears to reciprocate, then admits that Silver will never be anything more than an animal to him. While a more seasoned woman could figure out that Mietek is just passing time with her until someone better comes along, Silver is just a tadpole, and desperate for the musician’s love. Meanwhile, Golden picks up a guy at the nightclub when she’s not working and later slithers from his parked car to the water with his heart in her teeth. Male objectification and rejection may have their power here, but the mermaids are stronger, whether or not they’re ready to embrace that strength.

Golden encounters Triton, a fellow marine expat currently in human form, who explains why his horns are missing: a fisherman took one, and Triton pulled the other himself—another sea immigrant eager to alter himself in order to assimilate. But Golden is through with all that. She grabs and samples whatever she wants now. Triton warns her that if her sister gives up her fish tail for the coveted vagina and perma-legs of a human female, she will lose her voice. More important, he warns, if Silver’s human beloved marries another, she will turn into sea foam and be no more.

As Silver continues to sell herself short and Golden’s relationship to men becomes more and more predatory, Smoczyńska gives us one scene that proposes another option: a night that Golden spends with a military policewoman. The sex between them is powerfully erotic, not just because the two women are stunning but also because there is mutual acceptance between them. Unlike the men in the film, this cop has no fear of female genitalia, or of bloodlust. The two women sing a duet in which the policewoman promises, “I’ll take you to Disneyland, babe,” conjuring a delightful image of these two on Splash Mountain. The combination of one-night-stand ambivalence and desperation to join forces that the two actors project is singularly potent.

As one sister grows up, the other gives in. Silver lies on a bed of ice in an operating room like the catch of the day. She sings her last song, Golden singing along from home, encouraging Silver to get out of there. As the bone saw hits Silver’s waist, blood splatters, and her voice is silenced forever. The rest of her heals, though, and she learns to walk on her permanent legs and lifts her dress, revealing a bloody, stitched torso, to show Mietek her new vagina. They begin to have sex, but Mietek pulls away, disgusted. He will never accept her as a human.

This leads to the part of the original story the audience may recall with dread. There was always a moment at which the reader could hope the fairy tale would somehow turn out differently this time: the Little Mermaid would take her chance to stab her idiot prince and dive back into the water, voice and mortal seabound soul intact. Andersen wrote of his mermaid at her prince’s wedding: “She laughed and danced with the thought of death in her heart.” Disney gave us the deliriously happy ending they believed we wanted. But it took Smoczyńska to get it right.

Silver can’t bring herself to eat Mietek by dawn of the day after his wedding to a human woman on a party boat. The sun appears as he turns and looks confusedly at the green sea foam on his white shirt. It does not matter to Golden what value Silver placed on his life—Silver is dead. Her sister bites out the throat of the man who wronged her family, then jumps overboard as drunken wedding guests clamor. In this moment of revenge, Golden looks wild, truly out of control for the first time—and absolutely heartbroken.

The film ends with the camera panning across the floor of a seemingly vacant sea. Innocence is lost. Once it disappears, does something essential about us disappear with it, something we must all give up to be part of the adult human world, with all its misery? Maybe the only real choice any woman gets is this: do you want to be a Silver, or do you want to be a Golden?