Eyes Wide Shut: A Sword in the Bed

“When one is looking at a film, the experience is much closer to a dream than anything else.”

Stanley Kubrick, in a 1971 interview with Penelope Houston

In Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella Traumnovelle (Dream Story), a married couple, aroused by their adventures at a masked ball, confess past erotic fantasies. Rattled by his wife’s admission, the husband embarks on a night of failed sexual escapades. When he returns home, he slips into bed with his wife but “avoid[s] touching her.” She wakes and recounts a troubling, shockingly lurid dream. Afterward, neither can fall asleep. And so, all night, the couple lie in bed “as if there were a sword between us . . . lying here side by side like mortal enemies.”

The sword in the bed becomes the novella’s most potent image for the threat that female desire poses to traditional heterosexual marriage. Within every couple, male libido is presumed (but never spoken about), while female libido cannot be fathomed. When that equation is disrupted, the fundamental fragility of any marriage, or all marriage, is laid bare.

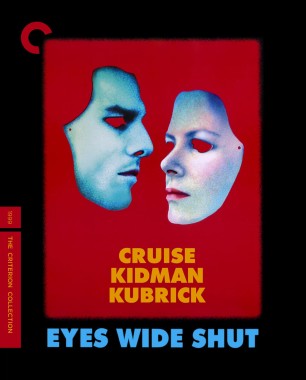

More than seventy years later, director Stanley Kubrick adapted Schnitzler’s novella—long a dream project of his—for what would be his final film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999). While he transplants the story from fin de siècle Vienna to contemporary New York City, Kubrick’s adaptation (cowritten with Frederic Raphael) is mostly faithful to the original. A successful doctor and his wife, Bill and Alice Harford (Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, married at the time), attend an opulent holiday party held by a wealthy patient of Bill’s (Sydney Pollack). The couple indulge in flirtations—Alice with a dashing older Hungarian man, and Bill with two very young models who offer to take him “where the rainbow ends.” The following evening, the couple have a charged, pot-fueled conversation about their respective near-dalliances that balloons into larger questions of male versus female desire. When Alice suggests that his female patients might want to have sex with him, Bill insists that women “don’t think like that.” Outraged, Alice replies, in darkly insinuating tones lifted directly from Schnitzler, “If you men only knew.” She then shares with him an incident from their previous summer in Cape Cod, when she spotted a naval officer for whom her desire was so consuming that she was willing to throw away her life for him: “You, [their daughter] Helena, my whole fucking future.”

The revelation leads to a dark night of the soul for Bill, roiling in jealousy and sexual frustration. He resists the advances of the grieving daughter of a deceased patient, nearly has sex with a young woman for money, and ends up hustling his way into a sinister masked orgy, seemingly risking his life and that of a young woman who seeks to protect him. Arriving home shaken, he finds Alice waking from a harrowing dream that mirrors his own misadventures, but with a difference: while Bill’s attempts at sex fail, Alice consummates her desire for the naval officer, among countless others—a variation on the orgy from which Bill was barred. The dream ends with Alice laughing at Bill, the ultimate humiliation. Both Bill’s near-indiscretions and Alice’s confession set off a marital crisis.