Le bonheur: Splendor in the Grass

Few films have inspired as many wildly differing interpretations in the decades since their release as Agnès Varda’s 1964 Le bonheur (Happiness). Is it a pastoral? A social satire? A slap-down of de Gaulle–style family values? A lyrical evocation of open marriage? Is the central character a good husband who knows how to enjoy life, a psychopath, a cad, or an unreal cardboard construction? Are the implications of the film’s title ironic or sincere? And, indeed, what is happiness?

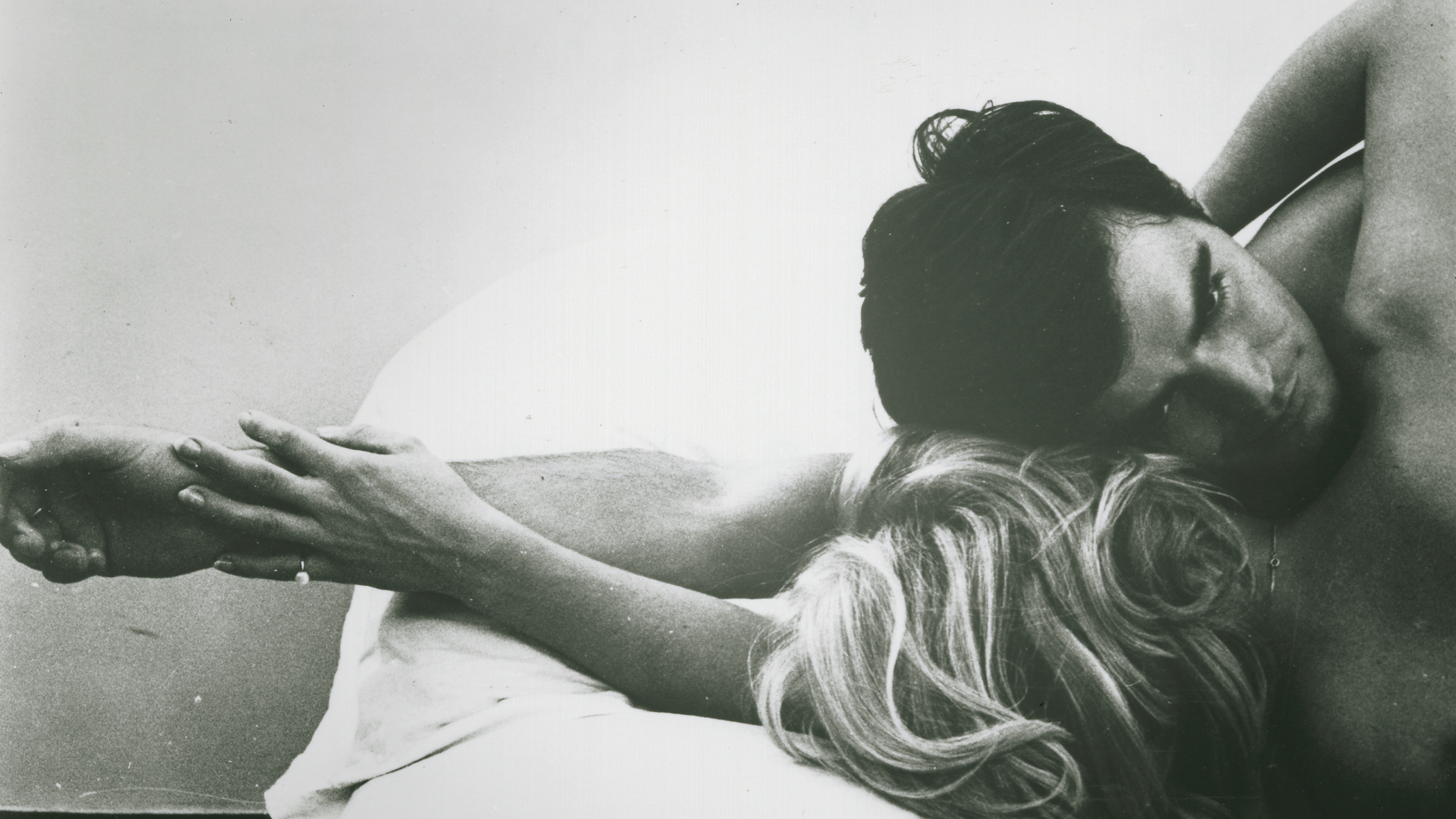

Set in a tiny suburb near but oh so far from Paris, Le bonheur depicts the events leading up to the collapse of a seemingly perfect marriage and the aftermath of this collapse. François, his wife, Thérèse, and their two toddlers enjoy a blissful life. Tall, dark, and handsome François works in his uncle’s carpentry shop. Pretty, buxom, blonde Thérèse is a homemaker who supplements the family’s income by doing a bit of dressmaking. They obviously adore their children, who never whine, almost never cry, and have the peculiar gift of falling instantly asleep anytime their parents want to make love—which is often. Varda cast the members of an actual family—French TV star Jean-Claude Drouot, his wife, Claire Drouot, and their children, Sandrine and Olivier—in these roles, and one wonders what they made of the totally conflict-free daily lives of their screen characters.

One day, while on a business trip, François spies Émilie (Marie-France Boyer), a pretty, blonde post-office worker who seems like a slightly more assertive version of his wife. By coincidence she is about to move to his hometown. They begin an affair, which soon has François dashing from his job to Émilie’s apartment at lunchtime and dashing home after work to snuggle with Thérèse before dinner and make love with her after dessert. After this routine has gone on for about a month, Thérèse asks François, during one of the family’s Sunday summer afternoons in the country, why he seems even happier than usual. Reluctant to lie to his wife, he tells her that he has a mistress, carefully explaining that since he has more than enough happiness to go around, nothing has changed between them. (Spoiler alert: if you have not yet watched Le bonheur, please save the rest of this essay for later.)

Discussing this scene in an interview with critic Gerald Peary in 1977, Varda remarked that at this point Thérèse’s reaction should have been “Go to hell! I want to be alone with you,” but if Varda had such a thought in 1964, it’s not evident in the film. One of the remarkable aspects of Le bonheur is that, regardless of how you, I, or Varda would act, or would like to think we would act, in a similar situation, there is no doubt that Thérèse’s response to her husband’s infidelity is the only response this character, in these circumstances, can have. Having defined her identity entirely in terms of the happiness she provides her husband, she hesitates only briefly before literally embracing a situation that is devastating to her. But while François sleeps contently after they’ve made love, she goes off and drowns in a nearby pond. Which is one way—unfortunately the most self-destructive—for Thérèse to tell François to go to hell. To be precise, since the drowning takes place offscreen, we never know whether Thérèse intentionally commits suicide or, wandering distraught, gathering flowers like Ophelia abandoned by Hamlet, accidentally slips and lets the water do the rest. In any event, her death intrudes on François’ self-involvement as little as her life. After a month or two of mourning, he marries Émilie. The nuclear family is restored. “Le bonheur” continues.

Le bonheur was Varda’s third feature film, made three years after Cléo from 5 to 7 established her as a filmmaker to be reckoned with, the only woman allied to the powerful French new wave. While other new-wave directors, notably Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol, often focused on female characters, the women in Varda’s strongest films and the issues she raised around them throughout her career would not have appealed to or even have crossed the consciousness of her “brethren.” One can’t imagine Godard making a film in which a woman faces the possibility of cancer ravaging her body and perhaps ending her life, as in Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7. (When Godard’s female characters die, they’re victims of gunfire or a car crash, and they depart this world with their beauty intact.) And although Truffaut and Chabrol each made several films about women who fit the archetype of the “bad girl,” neither could have put on the screen such transgressive figures, such usurpers of masculine prerogatives, as Sandrine Bonnaire’s clochard in Vagabond (1985) or the middle-class mom (Jane Birkin) who falls madly in love with a fourteen-year-old boy in Kung-Fu Master (1987).

Even more challenging than her female characters are the questions Varda poses about female subjectivity. Who speaks for women’s experience and subjectivity in a society—global patriarchy—where women are conditioned from birth not to speak for themselves? Thérèse and Émilie in Le bonheur are extreme examples of women who do not speak, women who repress the knowledge of their own feelings and desires, lest they come into conflict with their husband’s or lover’s “happiness.” When François and Émilie are beginning their affair, she hesitantly asks him about his marriage. François responds with a three-minute monologue, filled with clichéd metaphors and easy rationalizations, that ends with him comparing Thérèse to “a hardy plant” and Émilie to “an animal set free,” followed by the punch line “And I love nature.” To which Émilie replies, “That’s quite a speech,” and then falls into his arms. Later, when François tells Thérèse about his affair with Émilie, using yet another ludicrous nature metaphor (this one about apple trees), Thérèse blurts out one desperate question, “Will you live with her?” followed by a plaintive attempt to explain how unfair the situation is: “But you are the only one I love. I am your wife.” After that she capitulates. And when Émilie replaces Thérèse in the “wife position,” cheerily scrubbing the dishes and dressing the kids, she loses the tiny spark of independence she once had, murmuring to François as she curls up next to him in their narrow bed, “You are my happiness, you are my life.”

This is the kind of happiness the men of Stepford imagine when they refabricate their spouses as androids, and it’s not impossible that Le bonheur was an inspiration for the satire/horror of The Stepford Wives (1975). The two films are separated historically by the rise of the women’s movement at the end of the 1960s (what is often referred to as the second wave of feminism). Varda has identified herself as a feminist throughout her career and was active in the struggle for reproductive rights in France from the early 1960s. But she has cited her involvement in the civil rights movement in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s as the experience that radicalized her feminist position. Central to the feminism that grew out of the civil rights movement was the issue of “consciousness raising”—that, in addition to legal, economic, and reproductive rights, women needed to speak out about their subjective experience and act in their own interests. (Varda’s 1977 quasi-musical One Sings, the Other Doesn’t attempts to place militant feminist issues around reproductive rights in a form that would appeal to a mass audience.) Looking back at Le bonheur from the other side of the second wave of feminism, one can read it as a not-fully-articulated call to consciousness that largely fell on deaf ears, and to a certain extent still does today.

Contradiction is central to Varda’s filmmaking strategy. The strongest of her later films—Vagabond and The Gleaners and I—are shaped from a counterpoint of voices. In Vagabond, the identity of the homeless woman found dead in the opening scene is constructed from many recollections of people she encountered during the last weeks of her life. In The Gleaners and I, Varda, doing her own kind of gleaning, turns her camera on dozens of people who live off the detritus of an affluent society. But there is no such commentary, and no outside observers, in Le bonheur. The happiness of everyone on the screen is predicated on their refusal to admit the possibility of contradiction, even when it’s flung in their faces. Thus, to cite one of the more hilarious examples of tunnel vision, François’ brother tries to turn his backyard garden into veritable country wilderness, oblivious to the sight of three giant high-rise buildings that have sprouted only a kilometer or two away. Similar high-rises are the location of Godard’s great 1967 Two or Three Things I Know About Her (its title an ironic refusal of the masculine omniscience just beginning to come under fire), a film that is also about the perversity of de Gaulle’s pro-family values. But Godard’s critique is directed at consumerism, a problem that doesn’t exist in Le bonheur. The heroine of Two or Three Things is a wife and mother who works part-time, with her husband’s tacit consent, as a prostitute, so that her family can purchase the products that define them as middle-class. In Godard’s A Married Woman, released the same year as Le bonheur, the titular heroine is the one with both a spouse and a lover. As she wanders around Paris, she speaks almost entirely in advertising slogans. In many ways, Le bonheur and A Married Woman are mirror opposites, but the problem women have in finding their own voice is the same in both films.

Compared with the media-saturated Paris of A Married Woman, the self-enclosure of the characters and the suburban town in Le bonheur takes on a desperate, last-stand quality. François works in his family’s business; he and Thérèse’s social life is limited to an endless round of family gatherings and celebrations. There is virtually no advertising to be found anywhere in the town, and in the one scene where a television is playing, it’s tuned to a broadcast of Jean Renoir’s Picnic on the Grass (1959), a film whose combination of pastoral with social satire is a model for Le bonheur. The town itself is color coordinated to the point of looking like a catalog photograph. What the characters see as “natural” Varda reveals as artifice. Throughout the film, she makes marvelous use of color, not so much to call up emotion as to distance us and make us question what we see. This is, in fact, her first color film, and she seems determined to invent her own ABCs for its use. Rather than employing traditional fades to black, for example, she ends key sequences with slow dissolves into solid color fields, most notably of red, blue, or white—the colors of the French flag. In this context, the name François also takes on a satirical edge.

More than Le bonheur’s feminist politics and the fact that they were slightly ahead of their time, it is on the level of form that the film is so unsettling and calls up so many contradictory interpretations. One need only look at the opening and closing scenes to understand the complexity of Varda’s strategy. Le bonheur begins with a montage of flowers and foliage growing wild in the countryside. The sequence is anchored by repeated close-ups of sunflowers, their jaunty yellow petals just a bit ragged and faded around the edges. The editing rhythms are extremely aggressive. It’s not pastoral beauty that Varda is forcing us to see but a wildness and asymmetry that defies conventional representation and, certainly, the clichéd metaphors François is so fond of employing. The montage is scored to a late Mozart woodwind quintet, its relentless vivacity undercut by its minor mode. Neither the image nor the music is quite as celebratory as it might immediately seem. Hardly the signifiers of pure happiness, they both take on an increasingly mordant tone, which doesn’t entirely dissipate when the camera turns its attention to the family picnicking in the grass.

When we return in the last scene to this same patch of countryside, it is already late autumn. All that’s left of the sunflowers is their dry stalks. Just as François has replaced one wife with another, Varda replaces the late woodwind quintet with an even later and darker Mozart chamber work—a transcription for strings of the melodic themes of the original piece. The dirgelike sound suggests that as the family, holding hands, walks away from the camera, into the shadowy recesses of the forest, it is already entombed.