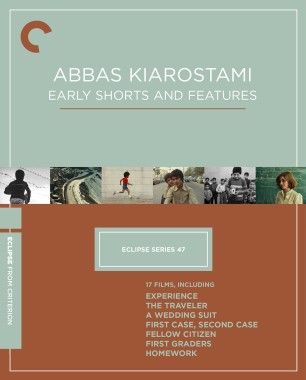

Abbas Kiarostami’s Early Shorts and Features: Poetic Solutions to Philosophical Problems

Abbas Kiarostami’s cinema is one of journeys. His films travel meandering routes, and his own path to international fame and recognition as one of cinema’s greatest directors was likewise mysteriously understated and subtle, almost imperceptible: a journey with marvelous detours.

Across a career marked by restlessness, which saw him making films not only in Iran but in France, Uganda, Italy, and Japan, the tireless filmmaker repeatedly reset his rules, moved from analog to digital, and transitioned from narrative film to video installations. Even as he came to be celebrated worldwide for beloved films such as Close-up (1990) and The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), whenever the conventional definitions of cinema became too limiting for him, he pursued creativity elsewhere. He rewrote classic Persian poems and published them in books of sparse, haikulike verses that resemble images, and he took strikingly abstract photographs of solitary trees in snow that feel like distilled poetry. His life was proof that a filmmaker could create singular images even without a movie camera.

His art of radical reduction persisted from the film title sequences he designed in the 1960s to his final, posthumously released 24 Frames (2017), serving as profound explorations of the relationship between photography and cinema, music and silence, artist and world. The deceptive simplicity of a seasoned master was evident in his cinema even a decade before he began harvesting awards at festivals around the globe, starting with Locarno’s Bronze Leopard for Where Is the Friend’s House? (1987) and coming into full flower with Cannes’s Palme d’Or for Taste of Cherry (1997).

The first two searching decades of his career, beginning in 1970, passed by relatively unnoticed and were discovered only in retrospect. Yet they contain some of his greatest films. The period of innovation and experimentation covered by this set reveals an artist reframing the world and relationships between individuals, demonstrating a uniquely creative engagement with nonactors, and producing philosophical works that reinvigorated both documentary and narrative-fiction cinema—often blurring the line between the two.

Like many filmmakers who have lived and worked through political upheavals, Kiarostami struck a balance between pure cynicism and profound humanism in his work, as it continually questioned life and cinema. Dividing his career into pre- and post-1979—the year of the Iranian Revolution—would be an oversimplification. Not only was there thematic and stylistic continuity between the two periods in his work, but there was also a significant institutional common thread.

With the exception of The Report (1977), all of Kiarostami’s films made between 1970 and the early 1990s—including all the titles in this set—were produced by the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, often referred to as Kanoon. Founded in 1965 by the twenty-seven-year-old Lily Amir-Arjomand under the direct order of Queen Farah Diba, Kanoon was one of a handful of progressive governmental institutions established during the last shah’s major cultural and social reforms of the sixties.

With the mission of promoting cultural literacy among children through the production of books, films, records, plays, and educational courses, dozens of Kanoon centers were established in cities across Iran, offering children free access to the arts. I, like many others, received my artistic education at these centers.

For artists and intellectuals, Kanoon was a blessing. It was politically progressive enough, in a country stifled by censorship, to open its doors to dissident filmmakers. One example was the appointment of Firouz Shirvanlou, a leftist and former political prisoner, to lead the foundation of its film department. He came up with the ingenious idea of inviting the Moscow State Circus to Tehran, and using the profits from its successful extended run at Farah Park, he financed Kanoon’s first seven film productions, including Kiarostami’s debut, Bread and Alley.