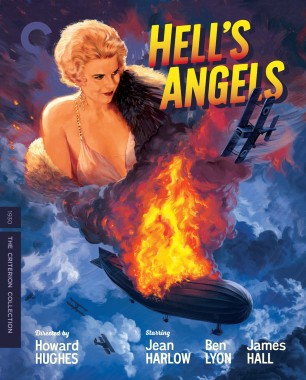

Hell’s Angels: The Sky Is the Limit

Howard Hughes’s Hell’s Angels, the 1930 adventure about World War I fighter pilots, must rank among the most underseen film classics. It is now perhaps best known from Martin Scorsese’s Hughes biopic, The Aviator (released seventy-four years later), whose opening scenes depict the young tycoon (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) commanding the trouble-racked film set. Scorsese captures Hughes’s obsessiveness—the key to a lifetime of extravagance—in getting the wartime details just right.

As far as it goes, the biopic is historically accurate. Hughes really did spend two and a half years and four million dollars making the movie (up till then, Hollywood’s longest shoot and highest budget). He really did buy eighty-seven vintage planes and hire more than a hundred pilots, creating, as DiCaprio’s Hughes calls it, “the largest private air force in the world.” He really did shoot some of the film’s dogfights from inside one of those planes himself.

But Scorsese, though quite the obsessive in his own right, omits several jaw-dropping facts. In the course of making the film, three of Hughes’s hired pilots and one mechanic died. (A district attorney looked into filing charges of negligent homicide, but the evidence fell short.) Hughes himself, a trained (but hardly expert) pilot, crashed a plane while attempting a spiral dive, suffering a concussion and requiring facial surgery. As a sign of his profligacy, he ended up shooting 2.5 million feet of film for a movie whose final print took up less than fifteen thousand feet.

More than this, The Aviator skips over the historical breakthroughs of Hell’s Angels. It marked Hughes’s directorial debut (sparking his rise as a cultural celebrity) and the first major screen appearance by Jean Harlow (uttering the immortal line “Would you be shocked if I put on something more comfortable?”). It stood at the nexus of the film industry’s broader transitions from silent to sound and from black and white to color. Perhaps most significantly, it heralded a shift in the cinematic portrayal of war, from rah-rah sentimentalism to jaundiced realism.

In this sense, it was Hollywood’s first modern portrait of the conflict that had ended just a dozen years earlier, killing more than fifteen million people and ravaging a continent—the first film to dramatize the dread and disillusionment that an entire generation had absorbed but much of popular culture was evading.