The Thief of Bagdad: Arabian Fantasies

For centuries, a double helix of fact and fiction about the East has spiraled into legend and entered the West’s popular imagination. Inevitably, cinema quickly tapped into a reservoir of oriental tales to quench its thirst for romantic fantasy, adventure, and spectacle. From early classics such as D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), Rudolph Valentino’s The Son of the Sheik (1926), and Cecil B. DeMille’s Cleopatra (1934), cinema was fascinated with the East, and picture palaces fixed an idea of it—sexy, strange, excessive, exotic—in people’s minds. Raoul Walsh’s The Thief of Bagdad (1924), which starred Douglas Fairbanks, provided the British-based, Hungarian-born producer Alexander Korda with a model for what he wanted to achieve fifteen years later, when he came to make his own version of the story: a supremely confident demonstration of mesmerizing visual effects, this time in Technicolor, boasting what his production company could do, and all wedded to a story of childlike adventure and genuine escapism.

Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad has the dazzling palette of Disney’s 1930s animations, and although it has crossover appeal to adults and children, like Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), and The Wizard of Oz (1939), it has become a classic beloved particularly by the young, not least because of the winning charm of its teenage hero, played by Sabu. It was Korda’s all-out attempt to reestablish himself in the industry, a big-budget splash of a film with state-of-the-art tricks, adopting the popular fantasies about the East but tailoring them for a young audience, as he had with Elephant Boy in 1937. Can this, though, fairly be called Korda’s film? Surely, yes, The Thief of Bagdad is as securely linked to its producer’s name as its near contemporary Gone with the Wind is to Selznick’s. A number of directors worked on it, including Michael Powell, and we can certainly see in it early traces of Powell’s style, but it was Korda who held the complicated production together. It was his expensive gamble and primarily his achievement. Both Selznick and Korda were moguls working on an epic scale (and note, incidentally, how readily Western cinema imported and mystified that Eastern word to describe its most potent grandees). Fairbanks had played the central role of Walsh’s thief with earthy gusto and roguish charm, and his muscular, balletic energy carries the film along. Korda, with his keen sense of how bankable his roster of contract stars were, wanted a key part for the beloved young Sabu. He therefore split his hero in two, and transformed the thief into a boy, Abu. What was sexily attractive in Fairbanks’s thief became playground japery in Sabu’s. Meanwhile, John Justin was cast as Ahmad, the romantic lead. He may well have had matinee-idol looks to compete with Fairbanks, but shorn of the robber’s guile his character lacks the roughness of his predecessor. For all the darkness that Conrad Veidt brings to the adventure as the villainous Jaffar, Korda’s version is more genuinely family entertainment.

The two versions of The Thief of Bagdad do share as their main source the set of tales generally referred to as The Arabian Nights: stories circulated orally and in written form over hundreds of years, originating in many countries—Arabia, India, Persia, and Egypt—and mixing real people and places with fantastical elements. These tales were collected and translated into bowdlerized French by Antoine Galland in 1704, under the title The Thousand and One Nights, and they helped to generate a sense in Europe that the East was a place of magic. Galland’s influence reached down to romantic writers like Beckford, Shelley, Byron, and Coleridge, and some of the tales’ characters, such as Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sinbad, became household names. Fragments from The Arabian Nights live on in Korda’s film: a bottled djinni; a leader going in disguise among his people; a sultan’s Palace of Pleasure and Garden of Gladness; and the grand vizier Jaffar, counselor to another of the tales’ central characters, Caliph Harun al-Rashid.

If The Arabian Nights gives us a rich, if fanciful, sense of the texture of the Arab world, we should remember that the stories are only half fancies, for Harun al-Rashid (his name means Harun the Well Guided) really did preside over Arab civilization from 786 till 809, a period often regarded as its golden age, and he had a real vizier called Jaffar (Jaffar al-Mansour), whom he eventually had beheaded. Korda, however, distanced himself from history with his Ahmad, said in the film to be the grandson of al-Rashid, and though the figure of Jaffar the vizier survives, he is now the nefarious heavy.

The chief premise of the film’s story is that Bagdad has a crisis of leadership, with a king who is far from “well guided.” He is detached from his people, too swayed by his chief minister, and then cruelly usurped. For all its fantastical register, then, this is not simply innocent fantasia, because it is working through ideas about political leadership that are colored by centuries of interaction between West and East, and between leaders and the led. As such, it can be seen alongside other instances of imperial culture, like Rudyard Kipling’s Kim and A. E. W. Mason’s The Four Feathers (filmed epically by Korda just before The Thief of Bagdad). It is set in present-day Iraq, of course, a nation forged under British administration when the end of the First World War brought an end to Turkish claims to its former Arab provinces. By 1921 the British had established a monarchy in Iraq under King Faisal, and the following year a treaty of alliance between Britain and Iraq was signed. In practice the treaty was a mandate, securing British involvement in Iraq and frustrating its national hopes, and Britain’s Jaffar-like influence over the infant state carried on for a decade, until full independence (with British interests secured) was negotiated in 1932.

None of this, of course, was at the forefront of Korda’s mind when he set about fabricating his fantasia, though in a sense the political context in Europe during the film’s production period certainly impinged on him. Extra directors were brought in, working with separate units to accelerate filming. It was a race to complete the shooting through the spring and summer of 1939, before Britain’s declaration of war on Germany brought the project to a sudden, unfinished halt in September. Korda immediately shifted his attention to the propaganda piece The Lion Has Wings (1940), to demonstrate the effectiveness of cinema in wartime. Work on The Thief of Bagdad was then moved to America, where it was completed the following year.

In 1938 Korda had lost control of Denham, the studios he had built up, and in March 1939 he had repositioned himself in the industry by forming Alexander Korda Productions. He was not just gambling financially on The Thief of Bagdad, then: this was as much a personal investment, and his prowess in the industry depended on its success. The production was beset with power struggles between Ludwig Berger, nominally the contracted director, and Korda. Berger’s role ebbed away as Tim Whelan, Michael Powell, and William Cameron Menzies were given units to direct, and then some deft politicking was needed to get Berger to drop his preferred composer, Oscar Straus, and take on Miklós Rózsa. By late summer, Berger was faded out entirely, though Korda remained the controlling influence.

This kind of power play is acted out in the film. What The Thief of Bagdad shows us is that exercising authority legitimately calls for the most careful and balanced consideration. One memorable sequence encapsulates this: young Abu finds a bottle washed up on a beach and unthinkingly releases the djinni trapped inside it; quick-wittedly he then recognizes the malevolent force he has unleashed and tricks the djinni back into the bottle until more “favorable terms” can be negotiated—he will have authority over the spirit until his first three wishes have been granted. Elsewhere in the film, the foolish Sultan of Basra (Miles Malleson) wishes his living subjects were as obedient as his magic puppets, a delusion that proves fatal when one particularly seductive new toy, the Silver Maid, plunges a sharp stiletto into his neck.

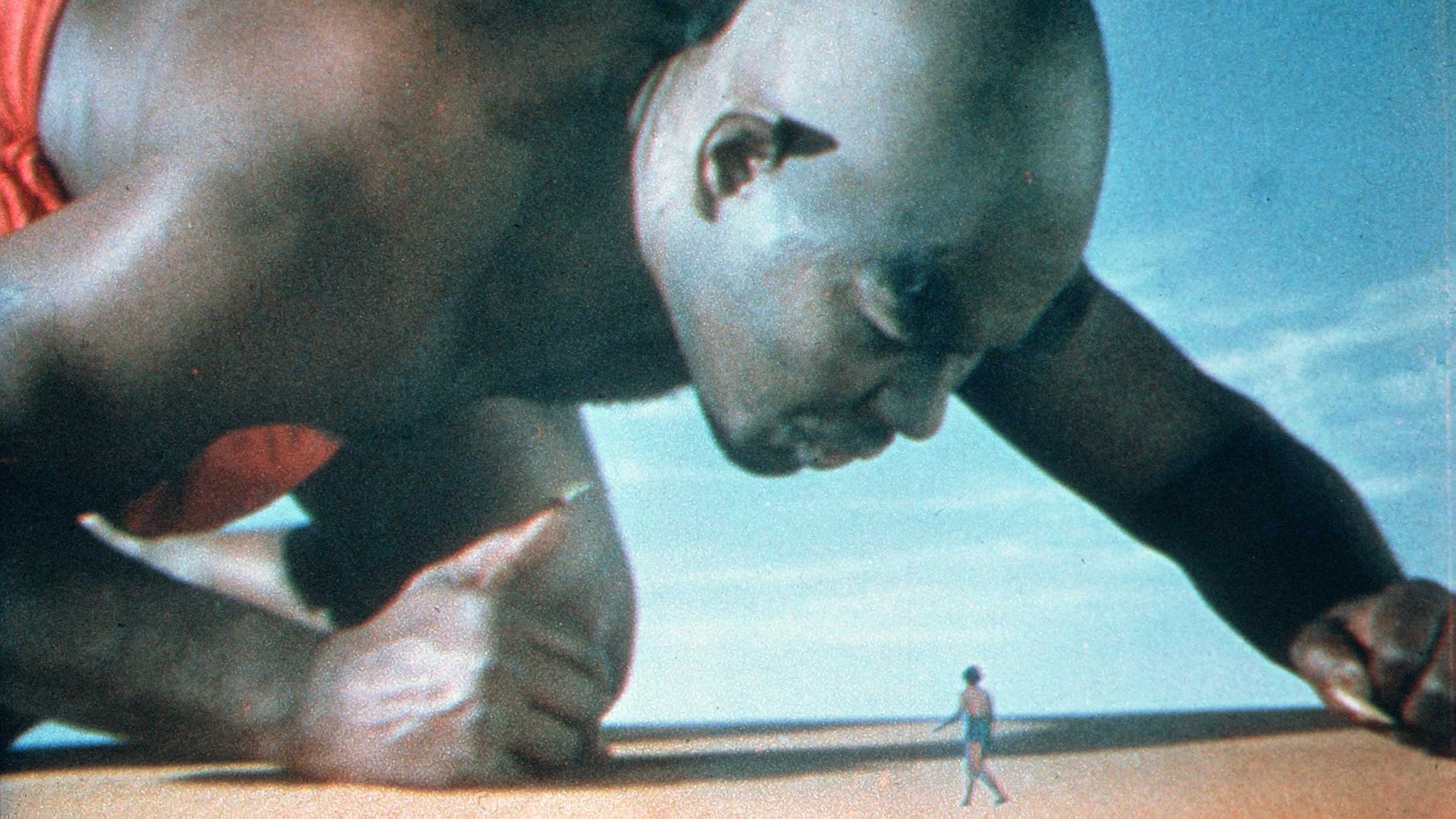

Abu’s “three wishes” routine with the djinni is a fabled scenario, enacting some of the delicate, dangerous judgments written into many power relationships. Is the treaty firm? Will Abu, a headstrong and sometimes streetwise boy, use his power wisely or squander it? Is the djinni bound to his pledge of loyalty? Is the giant paradoxically enslaved to the small child who liberated him? I use the word enslaved deliberately. The loinclothed black American actor Rex Ingram plays the djinni, and an early script for the film had him greet his emancipation with a “Song of Freedom.” A later synopsis referred to the as-yet-uncast character as “Robeson-Djinn,” so we can speculate that Paul Robeson, who had worked with Korda on Sanders of the River (1935), might have been in the scriptwriters’ minds to play the part. Robeson’s very career, of course, was underpinned by politicized race. All of which indicates that this so-called Arabian fantasy—shot in the sugar-candy shades of three-strip Technicolor—is brushstroked through with our world’s all-too-real politics. And if Ingram’s presence implicitly embodies a history of slavery in the United States, Sabu’s neatly signals one of British colonialism. Sabu, of course, is one of the film’s chief draws, and it was made as a vehicle for him and Conrad Veidt, two émigrés at Korda’s court. Sabu had first appeared as Toomai in Elephant Boy, a production that was partly filmed in India but that brought Sabu to London, leaving behind a life in the service of the Maharajah of Mysore. The popular success of Elephant Boy led to a long-term contract from Korda. Sabu then appeared as Prince Azim in The Drum (1938), playing a young friend to the agents of Victorian imperialism on India’s North-West Frontier, helping to overcome a fanatical Arab usurper. By the time of The Thief of Bagdad, he was a fifteen-year-old international star.

With the adult characteristics of the original thief vested in John Justin’s character, Abu is infantilized (despite being on the brink of a rather physically toned manhood). His character seems younger than Sabu’s fifteen to sixteen years. Through an insistence on his bare brown skin, he is also exoticized. These ways of representing the Easterner are typically orientalist—that loose set of ideas, fantasies, and prejudices about the East that props up a colonial sense of superiority but that, perhaps paradoxically, often exposes anxieties about it too. What keeps Sabu tame, familiar, and unthreatening, perhaps, is that he plays a young man as yet uninterested in sex. Above all else he is playful. His “crimes” are excusable, he is fundamentally good, and the sense of Arabia we get here is—more or less—that it is benignly Disneyesque. All this suggests a film at home with colonial culture, and while the wicked Jaffar’s presence allows for an exploration of the vice of tyranny, Veidt makes him magnetic and attractive, and he stays leagues away from the “mad mullah” stereotypes played by Raymond Massey in The Drum and by John Laurie in The Four Feathers. There is a possible reason for this: the “historical” epics, despite their fictional status, work through genuine conflicts and crises of the British in India and Africa, involving clashes with Islam, and in gung-ho fashion opponents of the British get crude treatment. The Thief of Bagdad, meanwhile, is far less anchored to historical fact anyway, and the recent history of Anglo-Arab dialogue had not seen Islam present a significant threat to British interests. As such, this realm of fantasy seems pretty and innocent.

What, though, of Ahmad, the other half of the original thief and most clearly the inheritor of Fairbanks’s role in the previous film? Fairbanks’s thief forges a Horatio Alger–like path from rags to riches, earning the right to princely happiness through a series of “trials.” It is a classic quest narrative, morally endorsing the American dream of upward mobility, but displaced to “the magical East.” It is worth noting here how the Korda version serves a very different political purpose. Where Fairbanks’s thief is a common rogue made good, Justin’s character is a rightful leader wrongly deposed and learning through his experiences among the commoners that his people can be trusted but his vizier could not: about as succinct an endorsement of democratic monarchy as we could wish, and this from a nation whose royal family had recently been rocked by abdication and whose eyes were squarely facing the rise of totalitarianism in Europe.

Colonial texts like The Thief of Bagdad, to paraphrase Edward Said, need masculine heroes. Repeatedly, though, this is a genre where masculinity is complicated, where Western explorers mapping the unknown have to come face-to-face with radically different cultures. If our tales of distant lands make a spectacle of racially different bodies (and that is one of their prime functions), they often also cast a close and curious eye at the bodies of Western men. So the eroticized, stripped, and frequently tortured “heroes” of orientalist stories, suffering in alien territories, come to symbolize the testing, and possible undoing, of Western masculinity. The Four Feathers displays a debased and mutilated English soldier-hero disguised as an African outcast and branded on his forehead as part of his atonement for cowardice and of his path toward masculine redemption. David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962) explores similar territory and opens up the subtextual possibility that the disempowerment of the white male Westerner is not just an unwanted danger; it might be an unconscious desire, masochistic, (homo)sexualized, and/or coming from a sense of imperial guilt.

These explorer narratives deal with the danger or frisson of “going native,” of “crossing over” and identifying with foreign cultures and experience. When Western (white) actors appear in Eastern (nonwhite) roles, this “borderland” experience plays out in different ways. Justin in The Thief of Bagdad is similar to us but not. His lithe torso is often as bare as Sabu’s, and though nakedness makes them similar, Justin’s white skin is at odds with Ahmad’s racial status. We see Ahmad imprisoned, chained, sentenced to die, and memorably blinded by Jaffar’s spell—symbolic castrations at the hands of a more powerful man who is his usurper in government and his rival for the love of a princess. The narrative clearly needs Ahmad to suffer, to plow the depths, before he can win back his palace. That is his “character arc.” But because Ahmad is played so obviously by a white man, he has to be seen alongside other British men of empire suffering abroad and losing their tenacious grip on brittle Western masculinity.

Justin saw that certain aspects of his required performance might compromise his own gender certainties. Years later he recollected mortified embarrassment at the costumes Oliver Messel originally designed for him, “all flowing tulle . . . like a pink and blue cloud!” It shows how readily the Arabian fantasy genre can effeminize its men that Messel should initially consider dressing the hero so flamboyantly, but Justin was as much concerned about having to wear these clothes himself as he was about how unsuitable they were for tough guy Ahmad. Eventually the actor summoned the bravado to leave his dressing room and walk, with his entourage from makeup, the length of the Denham set dragged up in Messel’s costume (taking care not to flounce). When he submitted himself to the withering gaze of archpatriarch Korda, he was relieved that the mogul shared his horror (“Vot the fark is this?” Korda is alleged to have exploded, before ordering less “exuberant” clothes and preserving the temple of masculinity).

Despite the “political” threads woven through it, the New York Times found The Thief of Bagdad to be spun from “the innocent stuff of daydreams” and praised Korda for “reaching boldly into a happy world,” particularly given how troubled the times were. Certainly the sense of blithe escapism is there, and there were ripe reasons for the newspaper to applaud the carpet flight from reality. It forms part of a continued tradition of representing the East by purposefully occluding the reality of it, but here the film’s status as an Arabian fantasy is celebrated. We can certainly read the politics of empire, gender, and power from it, but the film insists that we keep a childlike vision, identifying with the young Abu, who in its last scene escapes the trappings of boring court life, power politics, adulthood, and (horror of horrors) marriage, in search of more adventure. It’s a film that happily refuses to grow up.