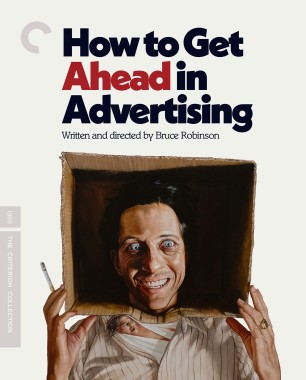

How to Get Ahead in Advertising

Our ad-inundated culture has had in it for decades a contrapuntal vein of satire—in fiction, plays, and films—to the point that satire on advertising is now a component of our advertising culture. What has changed, however, in recent years, is the focus of the satire. Originally, it was directed against Madison Avenue. Latterly, it has been aimed at the whole world that contains and accepts Madison Avenue as a life-giving artery. This phenomenon, the acceptance of advertising hype as a given—as probably untrue but who cares?—is the subject of How to Get Ahead in Advertising.

As Andrew Sullivan has written, “British skills in language, presentation, irony have been central to British domination, even in the United States, of the ad industry.’’ The author-director of this film, Bruce Robinson, uses skills in language, irony, and presentation to attack that domination. Robinson was an actor (the English lieutenant in Truffaut’s Story of Adèle H.), then wrote the screenplay of The Killing Fields, then became a writer-director for Withnail and I in 1987. That poignant film, about two young Englishmen leaving the 1960s, sticks in the mind: Its enlarged language and performance reflected a reticent culture in exceptional, heated conditions. How to Get Ahead takes this quality even further, as if the hothouse life of the ad agency were becoming not anomalous, but English society in extremis.

At the start Richard E. Grant (who played Withnail), a Copysmith Star-Class, is addressing a company meeting. He circles the table with a long speech in which he sets the ground for a forthcoming campaign, for all campaigns to come—a composite of the average British consumer, drawn with discomfiting perception, rapier slash. Every food they merchandise, he says, must be low in something. If not, it must be high in something else. But the new crisis he faces is daunting, despite his knowledge—not a food but a pimple cream. He must come up with a name for the cream and a campaign by Monday.

The film’s first half hour or so, bitingly comic, takes Grant through the storms of office crisis and personal torment, including a talk with his cool but adroitly pressuring boss. (On the boss’ wall hangs a copy of Sargent’s portrait of Henry James.) He even simmers at lunch with his wife, who is used to helping him through these tempests. What keeps us fixed in this first portion, full of familiar material, is the daringly virtuosic performance by Grant, the charm of Rachel Ward as his wife, the serpentine clamminess of Richard Wilson as the boss, and Robinson’s pyrotechnical writing.

Then the film, though still comic, changes mode—from fevered realism to symbolic fantasy. We are looking at the exterior of Grant’s luxe country house when suddenly two cartoon birds fly out of the chimney, swoop and flutter. This surprise Disney touch signals the shift. Grant develops a boil on his neck; the boil swells rapidly, then acquires eyes, a mouth—a voice. His wife of course thinks that he’s developed the boil under pimple-cream pressure and has flipped under the same pressure. A doctor is called, a psychiatrist is consulted, friends are insulted by the frantic Grant. In due course—due, that is, as the symbolism becomes clear—the boil, whose voice is satanic, grows big enough to take over the body of Grant himself while the original Grant, who had some traces of Good in him, himself becomes a boil on the Bad Grant’s neck.

The new Bad Grant looks exactly like the Good one, plus mustache, so he completely takes the other’s place, athletically enjoys his wife, and pushes any redeeming qualities of the former Grant right out of the picture. There is hope, however, because the pustule of Good still remains on his neck; but meanwhile the Bad exults in triumph and means to push on to even greater glories in Adland.

Paired with Withnail, How to Get Ahead establishes Robinson as a fine-tuned temperament and a keen mind with plentiful talent to use them both. A salute to the producers George Harrison, Denis O’Brien, and Ray Cooper for midwifing this eccentric, disquieting film. And a further salute to Grant, for whom Robinson quite obviously wrote the script. Grant has a voice and an ear, force and wit and lithe presence. Much, I hope, lies ahead of him.

This review first appeared in a somewhat different form in the June 5, 1989 issue of The New Republic. Reprinted with permission of the author.