Remembering Rob Reiner

Share

“These go to eleven.” “I’ll have what she’s having.” “You can’t handle the truth!” And of course, “Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.”

The humor and humanity of these lines and the movies that made them immortal—This Is Spinal Tap (1984), When Harry Met Sally . . . (1989), A Few Good Men (1992), and The Princess Bride (1987)—echo through the flood of tributes to Rob Reiner and his wife, photographer and producer Michele Singer Reiner, who were found dead in their home in Los Angeles on Sunday. Reiner is remembered as an actor who broke through in the most popular sitcom of the 1970s, All in the Family, and as an activist who spearheaded a winning campaign to establish same-sex marriage as a constitutional right in California.

As a cofounder of the independent production company Castle Rock Entertainment, Reiner was instrumental in the making of Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise (1995), John Sayles’s Lone Star (1996), Whit Stillman’s The Last Days of Disco (1998), Tony Gilroy’s Michael Clayton (2007), and dozens of television shows, including Seinfeld, a cultural milestone every bit as game-changing as All in the Family. Most of all, though, as we mourn, we also marvel at what the Atlantic’s David Sims calls “a chameleonic run,” a seven-film winning streak that began with Spinal Tap. “If you grew up in the ’80s and ’90s,” wrote Hadley Freeman in her 2018 Guardian profile of Reiner, “and went to the movies a lot, both of which I did, few people will have shaped your cultural landscape as much as Reiner.”

He grew up in the company of some of the greatest comedic talents of mid-twentieth-century America. His father was Carl Reiner, a writer who worked with Mel Brooks and Neil Simon on Sid Caesar’s variety shows in the 1950s, created The Dick Van Dyke Show in the 1960s, and launched Steve Martin’s movie career in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Rob Reiner knew his dad loved him but sensed that he didn’t understand him. A couple of months ago, he recalled weeping while writing a scene in Stand by Me (1986) in which twelve-year-old Gordie (Wil Wheaton) breaks down as he tells his friend Chris (River Phoenix) that his father hates him. Chris assures Gordie that his dad simply doesn’t know him.

The Actor

Norman Lear, the comedy writer who would go on to turn All in the Family into a sitcom empire, spotted the potential in young Rob before Carl Reiner did. Watching the kid play jacks, Lear baffled the elder Reiner with his observation that Rob was instinctively funny. As a teen, Rob Reiner became fast friends with Albert Brooks and formed one of LA’s first improvisational comedy troupes.

“When you do improv, you’re everything,” Reiner told Nathan Rabin at the A.V. Club in 2011. “You’re a performer, writer, and director, because you’re moving the scene in the direction you want it to go . . . I was nineteen, I was already directing my own improvisational group, and I directed theater in LA. I directed a production of No Exit with Richard Dreyfuss when I was nineteen. So I was already interested in directing when I was very young. I knew that was something I was going to be doing.”

In the late 1960s, partnering with Steve Martin, Reiner wrote for The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and took on bit roles in shows ranging from Batman to The Beverly Hillbillies. Then, after two auditions, he landed the role of Michael Stivic, the Polish American hippie his father-in-law, the irredeemable but also somehow endearing bigot Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor), called “Meathead.” From 1971 to 1976, All in the Family was the most-watched show in America, and Reiner won two Emmys for essentially playing the straight man to O’Connor’s cantankerous blue-collar worker.

“For Archie,” writes the New York Times’ James Poniewozik, “Michael was not just a handy foil—the righteous, longhaired interloper whom Archie resented for winning over his daughter and eating his food. He was the personification of a moment of history.” All in the Family was “a machine that ran on anger, and the two of them together were a fission reactor.”

Always a welcome and amiable on-screen presence, Reiner appeared briefly in his dad’s Where’s Poppa? (1970) and The Jerk (1979) and had slightly larger roles in Danny DeVito’s Throw Momma from the Train (1987) and Mike Nichols’s Postcards from the Edge (1990). He played the best friend of Tom Hanks’s Sam in Nora Ephron’s Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and an overbearing Marxist in Woody Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway (1994). On television, he’d pop up in Curb Your Enthusiasm, Hannah Montana, 30 Rock, and in three episodes of the latest season of The Bear.

The Director

Reiner’s funniest late-career performance may well have been his “Mad Max,” the father of the reckless broker Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) in Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street (2013): “$26,000 worth of sides?!” When Scorsese saw the first feature Reiner directed, This Is Spinal Tap, “he was a little upset I was making fun of him,” Reiner told the BFI’s Lou Thomas, “but now, over the years, he loves it. He’s come to love it.”

Reiner’s Marty DiBergi is a filmmaker following Britain’s loudest and most punctual band as they tour the States, playing to ever-dwindling crowds, bickering over green room snacks, and eventually breaking up. Marty’s conversations with band members David St. Hubbins (Michael McKean), Nigel Tufnel (Christopher Guest, who would carry on the mockumentary tradition with such films as Waiting for Guffman, Best in Show, and A Mighty Wind), and Derek Smalls (Harry Shearer) are blatant jabs at Scorsese’s interviews with Robbie Robertson and other members of the Band in The Last Waltz (1978).

In a piece we ran in September—just as the sequel, Spinal Tap II: The End Continues, landed in theaters—Alex Pappademas wrote that the original remains “maybe the most quotable and most quoted movie of the ’80s, a lingua franca for touring rock musicians and comedy nerds alike, not to mention the template for countless ersatz rockumentaries that followed.”

Teen sex comedies were all the rage during that decade, and as Mark Olsen points out in the Los Angeles Times, Reiner’s The Sure Thing (1985), “about two college students sharing a cross-country car trip together, had something special and different about it—namely the performances of John Cusack and Daphne Zuniga, who both brought an openhearted tenderness to a story that might have toppled into cynicism. The emotional earnestness that would often come through in Reiner’s work first emerged here, making what could have been a run-of-the-mill exercise into something more.”

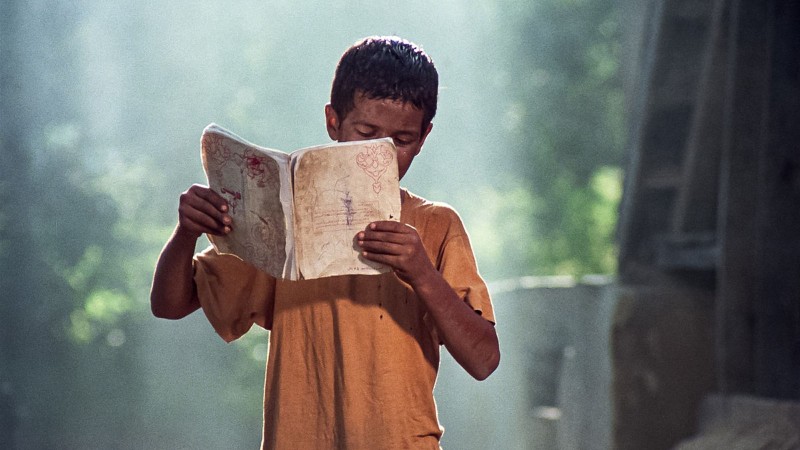

“Spinal Tap was satire, and I love satire, but that was something my father had done,” Reiner told Hadley Freeman. “And The Sure Thing was romantic comedy and he had done those. So Stand By Me was the first thing I did that was purely an extension of myself, and that meant a lot to me.” An adaptation of Stephen King’s 1982 novella The Body, Stand by Me tracks the journey of four young friends who go looking for the dead body of a missing boy. Of all King adaptations, Stand By Me is “the one I love beyond all measure,” writes the Guardian’s Xan Brooks. “It’s the warmest, the saddest, and the funniest, too: a lovely, grubby ode to the joys of misspent youth.”

“For my generation,” wrote Sloane Crosley in 2018, The Princess Bride (1987) is “not just a movie; it’s a facet of our adolescence and a building block of our worldview.” In addition to its “more obvious charms—the satirical humor, the range of insults, the perpetually windblown blonds, the Billy Crystal and Carol Kane cameos of the century—it manages to extract the exact tone and structure of William Goldman’s novel and put it onto the screen . . . With most adaptations, a few screws come loose in the process. But Goldman’s script and Rob Reiner’s direction of this story within a story are so adroit, one can only cringe at the idea of the material in anyone else’s hands.”

Written by Nora Ephron and starring Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan as just-friends trying to figure out whether or not they can keep it that way, When Harry Met Sally . . . is “hands down the modern era’s sharpest and most honest romantic comedy,” declares Amy Nicholson in the Los Angeles Times. Reiner and Ephron originally intended to have Harry and Sally go their separate ways, but then Reiner met on-set photographer Michele Singer, fell in love, and married her, despite the fact that she’d shot the cover of Trump: The Art of the Deal. “She has a lot to atone for,” quipped Reiner in his conversation with Hadley Freeman.

Reiner “had a great ear for what was funny,” writes Time’s Stephanie Zacharek, “but an equally sterling gift for knowing how a line could pierce straight to the heart, and he could guide his actors to that bullseye every time. Think of the moment Crystal’s Harry Burns says to Ryan’s Sally Albright, ‘I came here tonight because when you realize you want to spend the rest of your life with somebody, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible.’ There’s no syrup in it, only efficiency. Harry knows he’s almost out of time to make the future happen, and the words pour out at a thoroughbred’s clip.”

Kathy Bates won an Oscar for her performance in Misery as Annie Wilkes, the number one fan of romance novelist Paul Sheldon. When Paul crashes his car, Annie finds him and holds him captive, insisting that he write a new chapter for Misery Chastain, the character he created—and killed off in his latest, as-yet-unpublished manuscript. “That this 1990 Stephen King adaptation combines Rob Reiner’s innate gift for raising laughs with an acute sense of claustrophobia and suspense only makes it more impressive,” writes Ryan Gilbey in the Guardian.

A Few Good Men is Aaron Sorkin’s adaptation of his 1989 play about the trial of two Marines charged with the murder of a fellow Marine. The star-studded drama (Demi Moore, Kevin Bacon, Kiefer Sutherland, Kevin Pollak) is one long build-up to the courtroom standoff between Tom Cruise’s Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee and Jack Nicholson’s Colonel Nathan R. Jessep.

For the Guardian’s Gwilym Mumford, it’s Reiner’s “steady, unfussy direction that makes the whole thing thrum. A great director of actors, usually by just standing back and letting them cook, he also understood, and actually liked, genre movies, and in A Few Good Men his filmmaking actively leans into all the cliches and conventions of the courtroom drama—third act reversals of fortune, surprise witnesses, stirring, orchestral score and all. The result is propulsive and just the right side of preposterous.”

With North (1994), “Reiner’s reputation as a director notoriously took a sharp left turn,” writes Alan Sepinwall, who reminds us that the movie’s whimsy prompted Roger Ebert to write “perhaps the most vicious pan of his whole career, which included the infamous line, ‘I hated this movie. Hated hated hated hated hated this movie.’” Writing for the Decider, Glenn Kenny “wouldn’t recommend this as part of a home Reiner retrospective,” but “it can’t be dismissed as an entirely unrepresentative work. I’d reckon Reiner’s attraction to this globe-trotting fable in celebration of the family stemmed from Reiner’s own kindness, which suffuses all of his work. While his humor could be pointed, it was never mean.”

Reiner recovered somewhat with The American President (1995), shooting from another Aaron Sorkin screenplay, this one a forerunner to The West Wing. A few more notable films followed, including the box-office hit The Bucket List (2007) with Jack Nicholson and Morgan Freeman and a nonfiction tribute to an old friend, Albert Brooks: Defending My Life (2023). But while Castle Rock carried on producing solid work and Reiner’s activism bore fruit for the progressive causes he was committed to, that stretch from Spinal Tap to A Few Good Men was never matched.

“These were not just popular movies,” writes NPR’s Linda Holmes, “and they weren’t just good movies; these were an awful lot of people’s favorite movies. They were movies people attached to their personalities like patches on a jacket, giving them something to talk about with strangers and something to obsess over with friends. And he didn’t just do this once; he did it repeatedly.”

For Richard Lawson, writing in the Hollywood Reporter, “in 2025, when there is such a direly wide gap between a handful of worshipped auteur artistes and the relatively anonymous directors of everything else, Reiner’s deft marrying of the prestige and the populist seems like a wondrous, nearly lost art.” And as the New York Times’ Manohla Dargis observes, “despite his success, he always seemed like his best films: decent, principled, humane.”

Don’t miss out on your Daily briefing! Subscribe to the RSS feed.