Though there is a variety of sexual content depicted in the film, there is an innocent, fairy-tale-like quality to the story. This is another enduring element of Rollin’s work and can also be found in his films that focus on heterosexual romance, like The Nude Vampire and Lips of Blood. The latter follows Frédéric (Jean-Loup Philippe), who has hazy visions of visiting a castle by the sea when he was a child, where he met a beautiful girl (Annie Bell). He begins to believe these are not fantasies but suppressed memories. Frédéric becomes obsessed with finding the girl, a dangerous quest that draws him closer to dark secrets about his own family and into a nest of female vampires.

Frédéric is strongly motivated by nostalgia and fantasy, and his dreams of the vampire woman come to consume his life as he drifts further away from the human world. Folklorist Maria Tatar writes that the protagonist of a fairy tale is often a “traveler between two worlds” and journeys from a disappointing, ordinary life to find “strange, new realms.” This applies to Frédéric, and to many of Rollin’s other protagonists, who often embody a sense of innocence and wonder.

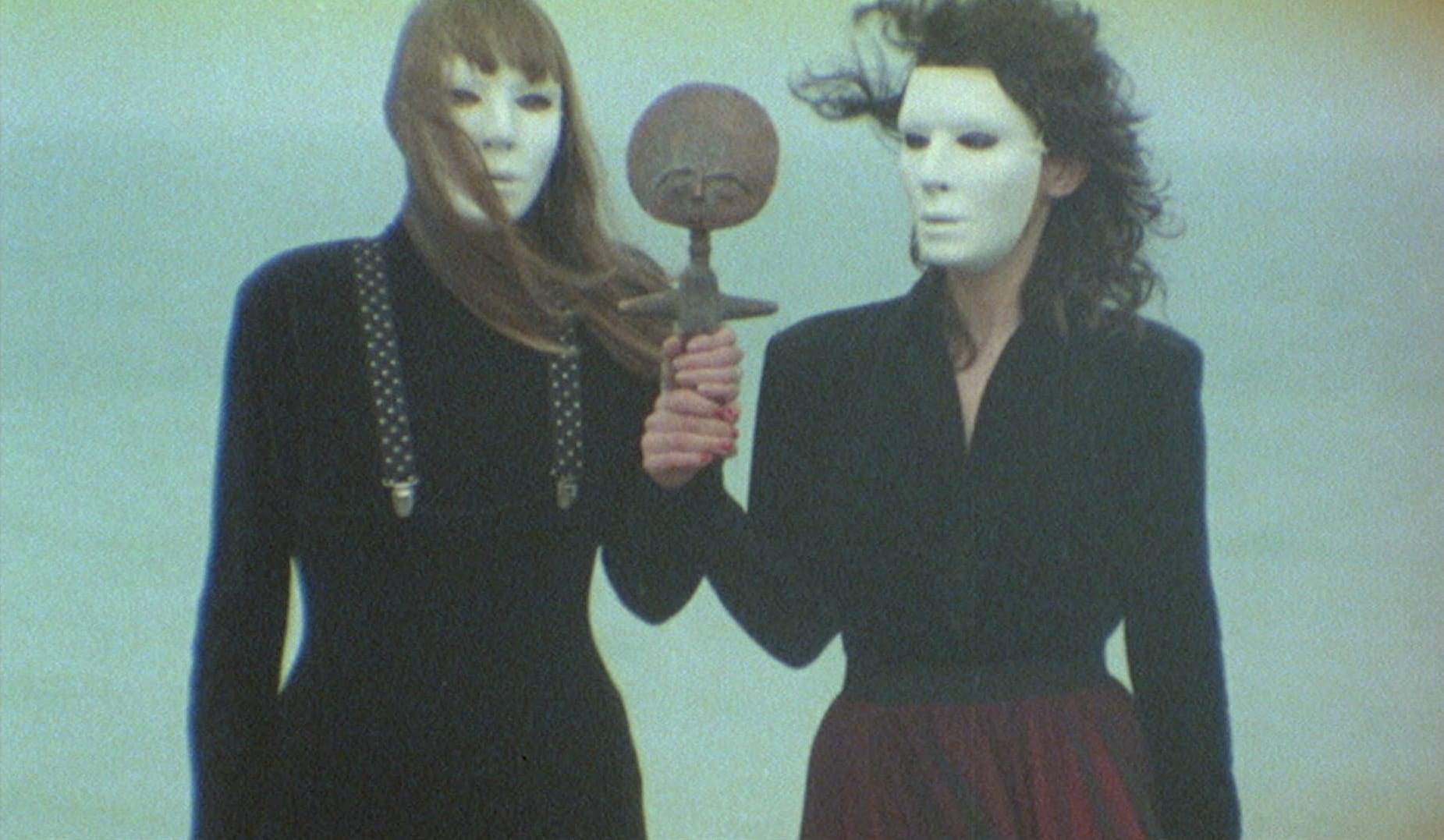

Jennifer, the vampire Frédéric is longing to reunite with, typifies Rollin’s unorthodox conception of vampires. In foundational stories like Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), vampires are little more than seductive, bestial predators who prey on humans to drink their blood. But for Rollin, vampires represent a romantic yearning for another way of life, and are possibly even an allegory for queerness: many of the female vampire characters in his films are implied to be bisexual. In this sense, Rollin was part of an emerging trend in vampire cinema in the early ’70s, when many European and some American directors presented female vampires as the lesbian seducers of young women, often newly married wives. Living death offered their mortal companions a chance at an entirely different society apart from the constraints of heterosexuality and bourgeois institutions. Other films that explore this trope include The Vampire Lovers (1970), Vampyros Lesbos (1971), Daughters of Darkness (1971), The Velvet Vampire (1971), and The Blood Spattered Bride (1972).

Rollin adapted this formula most directly with The Shiver of the Vampires, about a newly married couple visiting the bride’s relatives—vampire hunters who were recently transformed into the undead—at their family castle. The Shiver of the Vampires has an iconic sequence where the main female vampire, dressed like a contemporary hippie, unexpectedly emerges from a grandfather clock in the bride’s bedroom on her wedding night. This is an important example of how Rollin uses coffins, or other oblong boxes, as portals or gateways, transporting characters through time and space, sometimes figuratively but often literally. Often these characters are deposited on the beach in Dieppe, in the north of France, which appears in many of Rollin’s films and where he spent his summers as a child. A young woman inside or on top of a coffin is also a recurring visual motif. In Lips of Blood, the coffin takes on a more symbolic function: Frédéric and Jennifer climb into one and drift slowly out to sea, to an uncertain future.

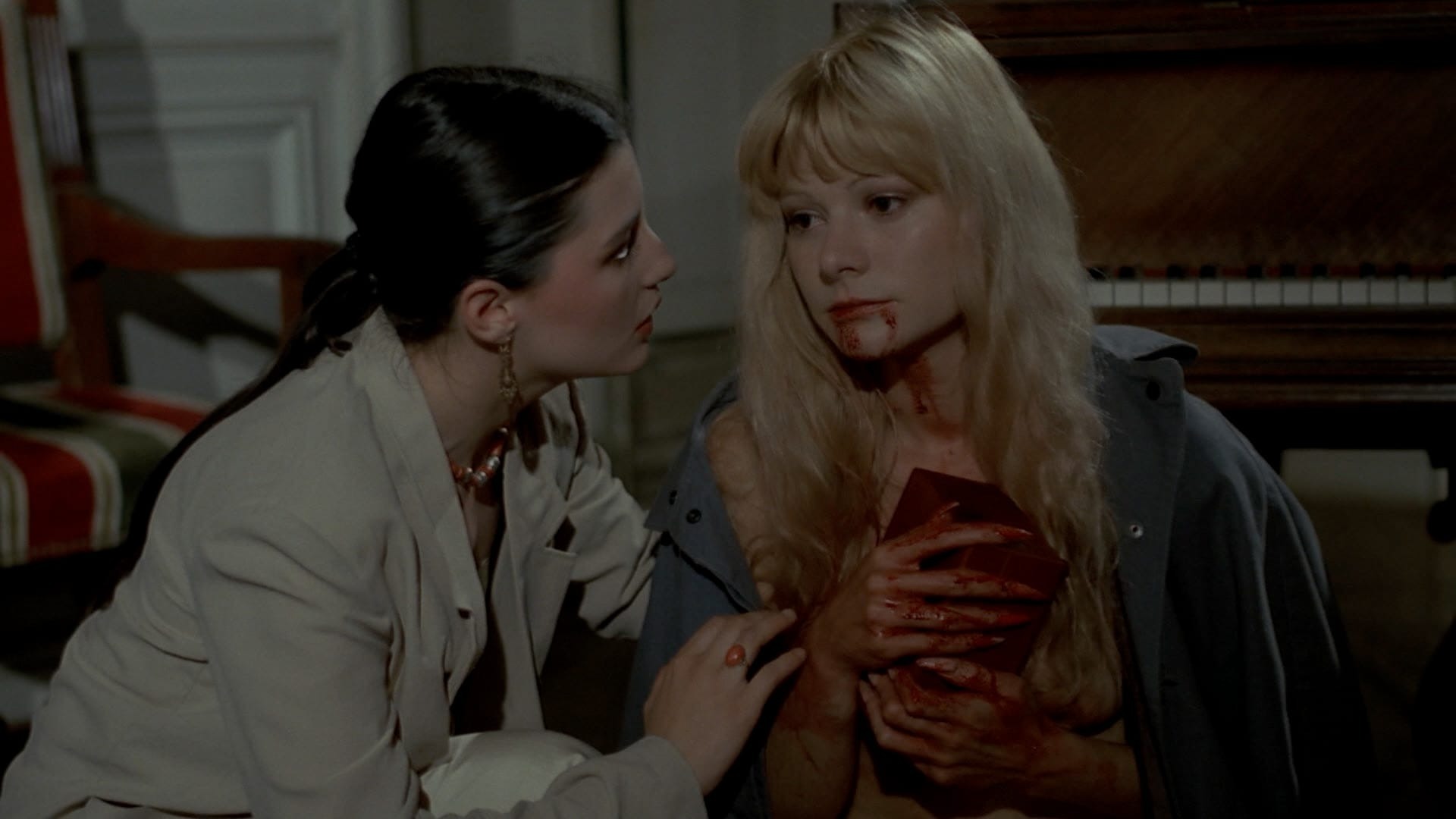

Even when this trend waned later in the decade, Rollin continued to explore female vampires as figures of romantic and sexual liberation, the physical incarnation of a freedom that surpasses even death. He would also begin to experiment with the limits of vampirism. In Fascination, a group of women form a secret society where they lure victims to drink their blood, sheerly for the pleasure of it. These voraciously sexual women are queer libertines of a sort; some of them appear to be wealthy and powerful, and they commit violence with impunity. It remains unclear whether this ritual blood-drinking has brought them immortality or supernatural power, though they seem to be only human.