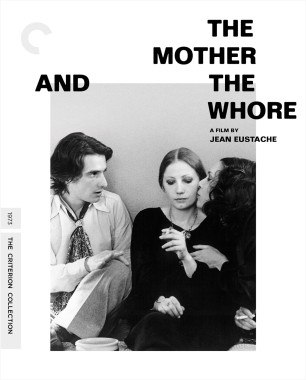

The Mother and the Whore: Lovers of Paris

The Mother and the Whore is Jean Eustache’s signature film, one of only two features he completed in his short life (1938–81). Although famous in part for its epic length, it is really a very simple film, a triangle picture like Casablanca or Jules and Jim, but with only a handful of characters altogether, and shot in the nouvelle vague terrain of real-world sets decorated by time and habit. Its primary constituent element is its text, which is driven, digressive, and argumentative, collecting in its folds the most urgent concerns of youngish people in Paris at the start of the 1970s. Its primary subject is the changing status of women and gender relations. Two-thirds of the way through, the film replaces one protagonist (bloviating, narcissistic, male) with another (wounded, self-aware, female). The replacement is the result of a competition of soliloquies. She wins the movie, flat out—but does she win at life?

From a working-class background in southwestern France, Eustache trained as an electrician, and after moving to Paris worked for the railways. But he became a regular at the Cinémathèque française, and his wife got a job as secretary at Cahiers du cinéma, so he was able to enter that milieu. He soon made a few fiction shorts (including 1966’s Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes, starring the twenty-two-year-old but already seasoned Jean-Pierre Léaud) and a couple of hour-long documentaries about rural traditions in his native Gironde. In 1972, he received funding to make a feature, thanks to his producer friend Pierre Cottrell, who got it from Bob Rafelson, after his enormous success with Easy Rider.

Few would put that film and The Mother and the Whore in the same category, but they were both generation-defining pictures, made only three years apart, that in their different ways represented the post-1960s comedown. For its part, The Mother and the Whore is an intensely interior movie, in both senses of the term, as well as very Parisian, less through photographic evocation than in the way that great cities determine everything about the social and cultural lives of their citizens. And that, here, is rendered mostly through speech. “The bias of the film is that everything is told and nothing is shown,” Eustache said. Léaud plays Alexandre, a young loafer who spends his time in cafés and sponges off his companion Marie (Bernadette Lafont), who owns a small dress shop. Despite the fact that they live together, he is constantly pursuing other women, employing a florid romantic technique that is obviously lifted from books and movies. He takes very badly his rejection by Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), a student, and compulsively reiterates all the postures you’re sure she has heard many times before, alternately grandiose, wheedling, insistent, stricken, superior, and finally dismissive.