Likewise, not only did A Woman of Paris make a star of Adolphe Menjou, elevating him permanently from supporting to leading roles, it also established his persona as a suave and worldly gentleman. Menjou wrote in his memoir, It Took Nine Tailors, that when he first got wind that Chaplin might have him in mind for a lead role in a new drama, he immediately realized what a great opportunity it would be and attempted to catch the director’s eye when he would run into him at Hollywood restaurants—for instance, by affecting a theatrically Gallic shrug on being informed that no, the kitchen did not have any escargots today, sir. In A Woman of Paris, this gesticulation has shrunk down from that ridiculous pantomime to a much smaller, more refined gesture, and in the process takes on a mean insinuation. Pierre shrugs, for example, when Marie asks about the identity of a young man dining with an older woman, dripping with jewels, “one of the richest old maids in Paris.” No need to say the word gigolo out loud. And in the film’s inspired final scene, the shrug reappears. It so happens that Pierre, while out for a country drive with a friend, passes Marie on a quiet lane. He doesn’t see her then, and perhaps he never really did. “By the way, whatever became of Marie St. Clair?” asks his companion, but Pierre apparently neither knows nor cares; he simply shrugs.

The language of gesture that Chaplin demanded of his actors was “like engraving the Constitution on the head of a pin,” Menjou wrote, “much to be told in a very confined space.” Restraint was the order of the day. According to Menjou, Chaplin insisted that the lights be set so low that some scenes came out black when they were printed and had to be reshot—albeit not an unusual expense for a Chaplin Studios production. Actress Lydia Knott was instructed by Chaplin to play the discovery of her son’s dead body with a blank face, and no wails of grief—it took a week for her to do this to his satisfaction. Sequences that promise escalating comic possibilities, such as the presentation of noxious “truffle soup” at a pretentious restaurant, are nipped in the bud. And after preview audiences howled with laughter at Chaplin’s cameo as a porter at the train station, he insisted on cutting it back to the bone. What remains of the scene, a heavily disguised Chaplin throwing a trunk with great force onto the ground, can be read as symbolic of his methods. Everything that called attention to itself was jettisoned, so only the human truth of the story remained.

When the film was released in late September 1923, critics fell into raptures over the refinement of Chaplin’s style, especially commenting on the scene in which Marie waits for her lover on the platform. Ingeniously, there is no train, just a gust of air and a series of shadows. When Pierre walks into Marie’s bedroom and retrieves a handkerchief from the top drawer of her dresser, Chaplin reveals the sexual extent of their relationship with just a single image. The innovations of A Woman of Paris immediately made waves. Ernst Lubitsch’s Viennese comedy The Marriage Circle (1924, also starring Menjou) was quickly compared to Chaplin’s film. Lubitsch’s deployment of “touches” that tell us more than the intertitles—such as when an unhappy marriage is portrayed simply via a glimpse of the husband’s worn-out socks and almost-empty drawers—is cut from the same cloth as A Woman of Paris’s eloquent restraint, and this minimalist innuendo became an essential part of Lubitsch’s subsequent Hollywood style. Although it is an exaggeration to suggest it was all borrowed from Chaplin, Lubitsch described A Woman of Paris as “a masterpiece—such genius.” He must have seen it at a prerelease screening in the summer, as the two films were made almost concurrently. “It may be said that there is not one Lubitsch, but two: one before and one after the appearance of A Woman of Paris,” said René Clair.

To understand how Chaplin came to make this landmark film, one needs to meet two of the women in his life. With one, he shared a lifetime of affection, more than thirty films, and a complex history. With the other, a notorious society figure, he engaged in what he later deemed a “bizarre, but brief” affair—an experience both thrilling and educational.

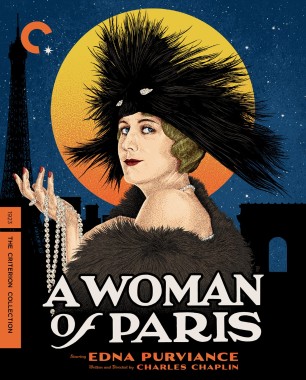

A Woman of Paris was Chaplin’s gift to Edna Purviance, his long-term costar and on-off girlfriend, whom one of his associates had discovered in a café in San Francisco in 1915. Chaplin hired this blond, quietly serious would-be actress more or less the moment he met her, only afterward worrying that her somber demeanor was not a natural fit for comedy. But after her first appearance in a Chaplin film, A Night Out (1915), as a straight-faced foil for Chaplin performing one of his famous drunk routines, it was clear that she had the knack, and they were soon romantically involved as well. Purviance played his sweetheart and comic partner in a long list of two-reel comedies, but her ability to convey a more melancholic tone elevated her appearance in funny films with a more serious intent, such as The Immigrant (1917), in which she plays a woman traveling to America with her sick mother. In the comedy-drama The Kid, she is prominent in the melodramatic story line of the film, but not the comic set pieces, as the tormented mother who has to give up her baby.

By the time of A Woman of Paris, the romance was a memory. It had been since 1918: famously, Purviance learned of the break between them when she read a newspaper report of Chaplin’s marriage to Mildred Harris. Purviance appeared to take the news in stride, quietly congratulating Chaplin at the studio the following day. There is a comparable scene in A Woman of Paris in which Marie discovers via a gossiping friend that Pierre has spent the evening with another woman. Chaplin spares us her pained reaction, with the camera lingering instead on the rising outrage on the face of Marie’s masseuse, who pummels her flesh with increasing violence, a physical parallel to the emotional blows. Whatever Chaplin felt he owed Purviance, he intended to repay with A Woman of Paris, a star vehicle made when her career was faltering and, in his opinion, her looks and confidence were suffering from her increased drinking.

Peggy Hopkins Joyce was an entirely different matter. This much-married actress and model had such a scandalous love life that she allegedly inspired the term gold digger. “True love,” she wrote in her salacious memoir of 1930, Men, Marriage and Me, “was a heavy diamond bracelet, preferably one that arrived with its price tag intact.” She and Chaplin met in 1922, after her third divorce, and actress Colleen Moore, who was also present, recalled how Joyce captivated by “showing just enough thigh to whet a man’s appetite,” flashing a smile, and swearing copiously as she drained glass after glass of champagne. They made a high-profile couple, and Photoplay magazine felt entitled to comment that, “in Peggy, Charlie found the greatest sex-lure he had ever encountered.” Joyce was dressed in black on that first meeting, in mourning for her Chilean lover Guillermo Errázuriz, who had recently shot himself. She had been seeing him on the side while she was involved with a Parisian playboy named Henri Letellier, and according to Joyce, Errázuriz pulled the trigger because she refused to marry him. Joyce entertained Chaplin during their fling with such colorful tales, and he squirreled them away for a project—which turned out to be A Woman of Paris. The fictional Marie therefore combined Purviance’s grace and capacity for forgiveness with Joyce’s sexual impropriety and precarious social position. The implication of the film is that just one year in Paris, covered by the fig leaf of a single intertitle, was enough to degrade a faithful sweetheart into a kept woman.