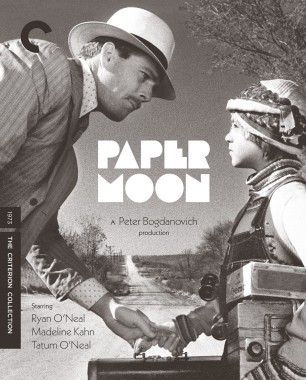

Paper Moon: Partners in Crime

The first thing we hear in Peter Bogdanovich’s tragicomic treasure Paper Moon (1973) is an old recording of the 1932 title song by Harold Arlen, E. Y. “Yip” Harburg, and Billy Rose, a reflection on the seductive power of falsity that keeps returning to the plaintive refrain “It wouldn’t be make-believe / If you believed in me.” The idea in that lyric is that true love has the power to transfigure the cheap and chintzy; it’s a sweet thought. But the first thing we see in the movie is the stony face of nine-year-old Addie Loggins (Tatum O’Neal), who is not about to be taken in for a single moment by wishful romantic malarkey like that. Addie is standing at the grave of her mother, who has been killed in a mill accident. It’s 1936, several years into a Depression that, in this part of rural Kansas, shows no signs of lifting. She is shortly to embark upon a journey with the small-time-iest and most scrounging of con artists, an itinerant salesman (Ryan O’Neal) with a ready smile. His name, he says, is Moses Pray. He is probably Addie’s father (we never find out for sure); reluctantly, he agrees to bring Addie to her aunt in Missouri, and to pay Addie back the two hundred dollars he has wheedled out of the man responsible for her mother’s death. Moze intends to be Addie’s teacher but winds up as her student; and though he fancies himself a better, smarter, shrewder thief than the irritatingly stoic youngster in his charge, he will spend most of the movie’s compact running time racing to keep up with her. She will eventually win his heart, if he has one, without even seeming to try. He will never know what hit him.

Paper Moon is many things: a road movie; a coming-of-age/getting-of-wisdom story; a caper comedy; an eye-level look at childhood, in all its wrenching disorientation and resilience, that manages to be both tough-minded and hopeful; and a tale about impoverished people in desperate times trying to make two and two add up to more than four. But one thing it refuses to be is an exercise in sentimentality. Moze, after all, is not just a grifter but one who exploits the vulnerability of his marks. He scans the papers for obits, then peddles cheap Bibles to the recently bereaved at huge markups by pretending they were ordered by the deceased as a final token of love. He’s nobody’s idea of a good guy—certainly not the movie’s.

Because Paper Moon was released at the start of a 1970s boomlet of Depression-era larks, it tends to get lumped in with the more eager-to-please films that came right after it, including Stanley Donen’s Lucky Lady, Bogdanovich’s own At Long Last Love, and George Roy Hill’s The Sting, also set in 1936, which opened eight months after Paper Moon and became a box-office, Oscar, and cultural juggernaut. But Paper Moon has little in common with any of those movies, nor does it pay homage to the films of the 1930s the way the same director’s smashing success What’s Up, Doc?, released a year earlier, did with its conscious nods to the screwball era. If anything, Paper Moon owes more to Bogdanovich’s 1971 breakthrough The Last Picture Show. Both movies, set in American small towns in the relatively recent past, are acts of defiant anti-nostalgia. Each is shot in black and white, but not in order to evoke the comforting world of old movies. Bogdanovich, the most cinephilic of all of the New Hollywood wunderkinder, came up as a film programmer at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The directors he most revered—Welles, Hawks, Hitchcock—used black and white for grit, for darkness, for the way it could connote reality. In Paper Moon, he takes that idea all the way; the result is a very funny movie that nonetheless looks as if it could have been shot by Walker Evans. (The cinematographer was the Hungarian émigré László Kovács, whose cool eye for alienated outsiders making their way across American vistas had already been tested in Easy Rider and Five Easy Pieces.) The era that Bogdanovich brings to life in Paper Moon isn’t the good old days. The narrative unfolds as a series of hustles and negotiations in underpopulated towns where you can practically feel the dust kick up into your nostrils, against drab landscapes that don’t look as if they could cough up a spare blade of grass. The film doesn’t even give us the comfort of a score (an idea Bogdanovich says he swiped from Rear Window).