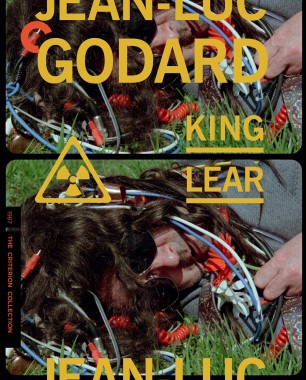

King Lear: After the End of the World

Jean-Luc Godard’s King Lear (1987) is the closest thing there is to a total film. It’s an adaptation that dramatizes the nature and even the possibility of adaptation; it’s a movie about the world of filmmaking that explicitly considers the conditions under which it was made and its own place in the art—and, for that matter, Godard’s. It enfolds the arts of theater, literature, painting, and music; it looks deep into the history of cinema while envisioning its future. Here Godard reconceives the basic principles of filmmaking, at every level, from the composition of images and the building of a soundtrack to the development of a story, the imagining of characters, and the unfolding of a narrative—from the selection of a cast and the performances of actors to the purpose and the power of editing. King Lear has the impulsive freedom and spontaneity of jazz, the contrapuntal intricacy and precision of classical music; the very elements of light and sound are as vividly expressive as if they were characters on their own.

Its original premise was a simple one: Cannon Films, a production company run by Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus that was among the most active and the boldest in mid-1980s Hollywood, financed a film by Godard that would be based on an adaptation of the Shakespeare play that Norman Mailer would write. Hollywood always loomed large for Godard, who, as a critic, played a vital role in the recognition of Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray, and other studio directors as major artists. For Godard, Hollywood was the cinema’s capital, in both senses of the word—its center of both power and money. He’d long hoped to make a movie there; he tried to do so in the late seventies, in a Mafia-related tale, under the aegis of Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope, and those efforts bore fruit, in a roundabout way, with King Lear, which was backed by a Hollywood mini-studio, was produced by Tom Luddy (who had also worked with him at Zoetrope), and featured major American actors. King Lear is also, in effect, Godard’s Hollywood movie in another regard—like the one he’d pitched to Coppola, it considers, tersely but potently, the very underpinnings of Hollywood itself.

Mailer indeed wrote the script—turning the play into a Mafia story, with the king transformed into a mob kingpin, Don Learo (pronounced lay-AH-ro). But Godard also asked Mailer to act in the film, as himself, and wanted Mailer’s daughter Kate, an actress, to play herself too. The movie opens with a sound clip, a recording of a phone call in which Golan complains to Godard that he’s taking too long to finish the film. That’s followed by the first scenes of action, two extended takes of one scene featuring the Mailers, in which Norman declares the script done, summons Kate, and then suggests that they quit the film and fly back home. In fact, soon after the filming of this scene, Godard and Mailer had an argument—over whether the writer could rewrite his dialogue—and the Mailers indeed withdrew. (According to Godard, Mailer left because he refused to deliver lines suggesting that he’d had incestuous relations with his daughter.)

King Lear embraces a wide expressive spectrum; its emotional range is extraordinary, from antic humor to tragic grandeur. But its fullness is also, in a sense, negative: the movie challenges deep-rooted assumptions about what a Shakespearean movie should be and, for that matter, about what a movie even is. As a result of its disparate tones and its self-undermining reflexivity, King Lear, far from being embraced as the supreme masterwork that it is, was roundly derided and vehemently mocked in its time. There is perhaps no more grotesquely, nearly unanimously disparaged masterwork than Godard’s film, which received an infinitesimal U.S. release on January 22, 1988, and went unreleased in France until 2002.