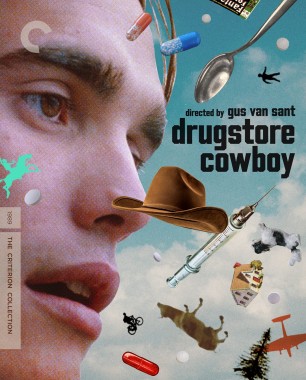

Drugstore Cowboy: Higher Powers

“The Northwest’s Odyssey”—that’s what the great Puget Sound–born writer Charles D’Ambrosio once called Ken Kesey’s 1964 novel Sometimes a Great Notion. What he meant by that, I think, was that Kesey’s swaggering tale of an antiunion logging family, the Stampers, stands as epic and originary, and possibly the ultimate reference point for any literature written in this region ever after. The book, like the landscape it describes, is a volcanic performance, a thing of great wildness and riverine digression. Charlie was also implying, truthfully enough, that the written word doesn’t go back very far in these parts. He was saying that our most ancient writings are only about three or four generations old.

By this way of thinking, one could argue that Drugstore Cowboy, the 1989 film directed by Portland, Oregon’s own Gus Van Sant, is our New Testament. Unlike Kesey’s novel, with its heroic, Homeric map of the territory, Drugstore Cowboy is a small, moral tale of mercy and transcendence, built on the suffering of a man whose faith is tempted by the tender flesh. It takes place in a provincial town, almost like Galilee, and involves revelatory trips to the hinterlands with a batch of disciples. It’s like the New Testament, too, in that the authorship splinters a bit under examination, and the final text bears traces of earlier holy scripture in its grain, ranging from the scrolls of beatnikism, to the trippy superimpositions of surrealist cinema, to the harsh transgressions of seventies underground film, to the cool stylings of film noir, all punctuated by the voice of an angel, Desmond Dekker.

The Book of Gus, you could call it, and among the first and only really great movies ever produced in the lower Columbia River basin. And while the religion it suggests isn’t exactly Christianity per se, it definitely grazes certain Christological structures of feeling. So what is Gus-ism, exactly? What is the rock upon which our church is built?

By 1988, the year of the film’s making, Gus Van Sant had already performed one miracle. It was called Mala Noche (1985), a film of such exquisite beauty it almost ceases to be cinema at all and enters the realm of pure poetry. Based on the novella by Walt Curtis, and made with very humble means, the film tells the story of a white store clerk named Walt who lives in tortured longing for an itinerant Mexican kid known as Johnny. It’s a skid-row story, unapologetic in its homoeroticism, and most of all a pretext for a sequence of black-and-white images that still feel kissed by the light that formed them. How does one follow up a miracle like that? It’s a question most of us will never have to ask ourselves.

If you’re Gus Van Sant, apparently, you decide to adapt an unpublished manuscript by an inmate in Walla Walla prison named James Fogle. The manuscript was called Drugstore Cowboy, an echo of Midnight Cowboy, Urban Cowboy, “Rhinestone Cowboy,” and any of the other cowboys floating around American popular culture of the mid- to late twentieth century, coupling with whatever modifier would have them. By the late eighties, the noun was much used and a bit diminished, which is to say well fitting for a story of small-time thievery in the vein of writings by Mickey Spillane or Jack Black’s cult crime memoir You Can’t Win.