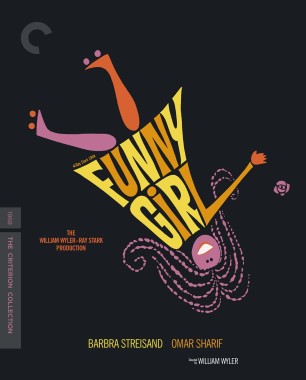

Funny Girl: A Feeling Deep in Your Soul

Barbra Streisand’s embodiment of vaudeville legend Fanny Brice in Funny Girl (1968) is more than iconic—it’s hardwired into American culture. When we think about William Wyler’s adaptation of the 1964 Broadway musical, what initially comes to mind is Fanny’s indomitability. After all, even in a genre intent on giving outcasts a spotlight where they can belt out declarations of grit and determination—a place where they ain’t down yet, where what they are needs no excuses, where nothing’s gonna stop ’em till they’re through—Funny Girl stands out for the unrelenting way it celebrates its heroine’s gumption. Fanny, the self-proclaimed “American Beauty rose with an American Beauty nose,” seems to run roughshod over all obstacles. Yet Streisand also plays her with such vulnerability and intimacy that the movie has far outlived the era’s other screen adaptations of stage musicals featuring strong-willed, independent women who won’t go down without a fight (including Gypsy; The Unsinkable Molly Brown; Hello, Dolly!; and Mame). Instead of making us passive witnesses to its protagonist’s rise, as so many biopics do, Funny Girl brings us into Fanny’s interior landscape.

Near the beginning of the film, we see the ambivalent, conflicted woman secreted inside the rambunctious stage performer. Lower East Side showbiz hopeful Fanny has just been fired as a replacement chorus girl. “You don’t look like the other girls,” scolds small-time theater director Mr. Keeney. “You’ve got skinny legs. You stick out!” Fanny then spends the next four minutes sermonizing on why he should take a chance on her, demonstrating her vocal gifts with the slam-bang “I’m the Greatest Star,” a self-promotional anthem so persuasive it would make Gypsy’s Momma Rose look like a shrinking violet. At the end of the number, Fanny collapses to her knees in triumph. But then this “pip with pizzazz” looks out into the cavernous theater (now empty, save theater assistant Eddie, sympathetically clapping), and her eyes, captured in close-up, are welling with tears. Why is Fanny crying? Is she exhausted from the vocal acrobatics? Fatigued from having made such a strenuous case? The simple answer is that she’s human. We may have just been astonished by her soaring voice, but now, seeing those watery eyes level with the camera, looking back at us, we’re one with her—and hooked for life.

The film’s synchronous razzle-dazzle and psychological complexity shouldn’t come as a surprise to those familiar with Wyler’s career. There may not have been a Hollywood director more skilled at framing and blocking actors for prime emotional impact without succumbing to cloying sentimentality. Consider the human-scaled strength of Greer Garson holding down the home front in Mrs. Miniver (1942), Olivia de Havilland ascending the stairs in bitter victory in The Heiress (1949), and Audrey Hepburn escaping the constraints of life as a princess in Roman Holiday (1953). Streisand fits into this lineage of actresses as much as she stands alone for her singular, era-transcending star power. Funny Girl is a showcase for its dazzling new screen performer, and much of its appeal comes from how it documents a partnership between its director and the legend he’s helping to create.

A frequenter of operas and stage plays since his childhood in the Alsatian city of Mulhouse, where he was born into a Jewish family in 1902, Wyler was a classicist at heart (he cherished the memory of seeing one of Sarah Bernhardt’s final performances in Paris). He had a reputation for demanding compositional perfection, yet he worked in happy concert with collaborators, especially strong women. Among the most notable were the steel-spined warrior Bette Davis, who starred in Jezebel (1938), The Letter (1940), and The Little Foxes (1941), and the notoriously thorny Lillian Hellman, a lifelong friend of Wyler’s whose controversial play The Children’s Hour he adapted for the screen once in 1936 (as These Three) and again in a 1961 version truer to the source text’s lesbian subject matter.