The Grifters: City of Angles

When The Grifters was published in 1963, most of the literary world took no more notice than it had of Jim Thompson’s twenty previous novels. Thompson did have readers (among them many filmmakers and fellow writers) who recognized that his books of the 1950s—marketed as disposable drugstore-rack crime novels—in fact belonged to no genre but the one he had invented for himself, in which no free-form zigzags are off-limits and readers might find themselves falling through a trapdoor just when they were expecting a neat plot resolution. Underground enthusiasm had not, however, translated into wider recognition. The Grifters was no more despairing than the darkest of Thompson’s earlier books, but the cold-eyed grisliness of its finale did suggest a limit point of irredeemable nihilism.

Born in 1906, Thompson had survived family turmoil and rapid changes of fortune, soul-killing work, and much drifting around the roadhouses and oil fields of Depression-era America—writing stories for true-crime pulps and working as a project director for the Oklahoma branch of the Federal Writers’ Project—to find himself, at age fifty-seven, facing diminishing prospects and ravaged by years of alcoholism. He had collaborated with director Stanley Kubrick on the scripts for The Killing (1956) and Paths of Glory (1957), but nothing had come of Kubrick’s interest in an original script of Thompson’s. He followed The Grifters with the extraordinary Pop. 1280 (1964), and then his output became sparser. Sam Peckinpah made an excellent movie from The Getaway in 1972, but Thompson’s early script had unfortunately already been rejected, and the film substituted a happy ending for the 1958 book’s unforgiving final episode.

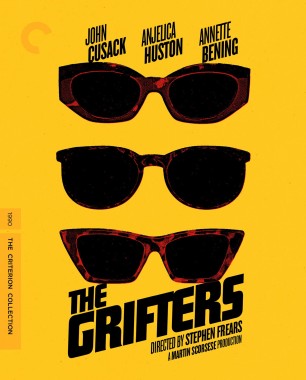

Sometime before his death in 1977, Thompson told his wife, Alberta Hesse, that he’d be famous ten years after he went, a prophecy that began to be realized even more rapidly than that. Alain Corneau’s film Série noire (1979) moved the 1954 novel A Hell of a Woman to a France of suitable dinginess, while Bertrand Tavernier with great success transposed Pop. 1280 to French colonial Africa in Coup de torchon (1981). Thompson’s books, almost entirely out of print in English, were reissued, and his rediscovery was sealed by a trifecta of Hollywood adaptations: Maggie Greenwald’s The Kill-Off (1989), James Foley’s After Dark, My Sweet (1990), and, most felicitously, The Grifters (1990), the first movie that the British director Stephen Frears made in Hollywood. Frears took a book that many would have considered unfilmable for its jagged narrative lurches and desolate emotional landscape, and uncovered layers of nuance and of compassion—not of the characters for each other but of Thompson for even the most perverse of the people he wrote about. The result is not a softening of the material but a profoundly attuned dive into the heart of Thompson’s sense of ineluctable suffering.