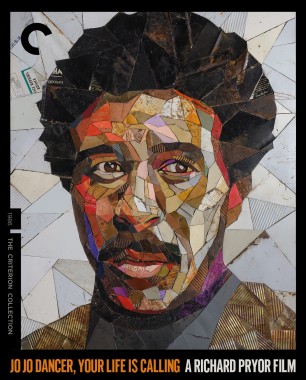

Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling: Songs of Innocence and Experience

Richard Pryor was and remains a great American artist. No other country could have produced this protean creator, a comedian who became a writer and actor who became a director, and, for the lucky few, a teacher who taught artists in all those genres that telling the truth was itself an art—and that, even if you didn’t follow his unique blend of social commentary, humor, anguish, and colloquial brilliance, you must learn to speak in a language that says more than you ever thought yourself capable of expressing.

He was also one of the last of the great artist-martyrs, a man who saw no separation between his body and the world that battered it, licked it, coddled it, and at times ignored his genius entirely because its existence was too much, a great overwhelming gift I first experienced on record. That was in the mid-1970s, when his masterpiece album, That Nigger’s Crazy (1974), was out, a time when it was practically forbidden to listen to Pryor, he was so outrageous, all that smut and diamonds buried in shit. Divorce, drugs, sex—it was all there in his stop-and-start, sometimes outraged voice when he told stories about his beginnings in Peoria, Illinois. His early days on the comedy circuit, when he more or less imitated Bill Cosby. Then his revelation after walking out on a gig in Vegas—a real tux-and-black-tie gig—before moving up north, to the Bay Area, where he met Black activists with powerful voices, Huey Newton and the like, in charge of their own narratives, while also listening to the voices they heard in the street. Putting his ear close to the ground, Pryor found his language: rough and tender, true to life, and scared about what could happen to his body in a world where shooting ranges always had black targets.

And even though That Nigger’s Crazy blew the top of my head off, I couldn’t entirely accept what he had to say. I listened to the record over and over again at my sister’s house when I babysat, laughing so hard because I somehow knew that everything he said was true. I was not an adult male, and Pryor was speaking out of that experience. But I could hear, as clear as a bell, the anguish. It was becoming clear what the world had in store for me. Pryor knew—I could tell by the depth of his feeling, his observations—that the joke was on guys like us, even though we knew those Othering guys were the joke.

Although I understood that Pryor was telling the truth—his best work reveals his beautiful heart (his greatest portrayals that he didn’t write himself are the tender junkie in “Juke and Opal,” a sketch from Lily Tomlin’s 1973 TV special Lily, and the worker in Paul Schrader’s 1978 film Blue Collar)—I couldn’t face, at times, what he was saying about being an American, about being a male, a Black male, because who wants to be a citizen in a world that does to its citizens what we do to ours? Richard Pryor taught me that you could use that—use this wretchedness and twisted ethos—to your advantage, in your art, as long as you were honest, and told the truth about how the world affected you, and why.