Tod Browning’s Ballyhoo Art

I. “Morbid Cinema”

On October 10, 1962, there appeared a brief paragraph from the Associated Press: “Tod Browning, eighty-two, who directed scores of movies between 1917 and 1939, is dead. He succumbed Saturday after an illness, and no funeral plans were announced. Born in Louisville, Kentucky, he began as an actor before turning to directing. His films include Dracula and Mark of the Vampire.”

The New York Times hardly did him a greater service. It ran a longer notice that same day but undercut its own work by crediting Browning with directing “Lon Chaney in his masterpiece, The Hunchback of Notre Dame” (Hunchback’s director was Wallace Worsley). Elsewhere, columnist Kaspar Monahan wrote that Browning’s “passing meant nothing to the younger generation—or the oldsters either,” although Monahan did remind his readers that Browning directed Chaney in West of Zanzibar (1928) and The Unholy Three (1925). Surely there were people to whom the name Tod Browning—trailblazer of horror and bard of the grotesque—still meant something. But there was a grain of truth to this gloomy assessment all the same. Browning’s last movie was released in 1939. His wife, Alice, died in 1944, and Variety, confused by Browning’s near-total lack of visibility in Hollywood since his retirement, had printed the director’s obituary instead. Maybe Monahan’s apparent pessimism was just realism.

The true irony, worthy of one of Browning’s own story lines, was that he died the very year his name began to regain some cachet with the general public. Little more than a month before those cursory death notices, Browning’s singular 1932 masterpiece, Freaks, screened at the Venice Film Festival in a section called “The Birth of American Talkies,” on a double bill with 42nd Street. Despite the odd pairing of Browning’s grim sideshow fable with 42nd Street’s wisecracking chorus line, the Lido’s glittering crowd was captivated by Freaks. But back in Santa Monica, Browning was deep in the grip of his last illness. As biographers David J. Skal and Elias Savada note, it’s unlikely Browning ever heard about the international audience that, at long last, had seen in Freaks not some misguided shocker but rather an unsentimental yet compassionate view of a world belonging to show business as surely as Broadway hoofers did. The so-called freaks of the film function as a family, distrustful of outsiders, protective of their own—just how protective being something you don’t want to find out the hard way. It turned out that the dawn of the 1960s was the perfect time to revive a director who dealt with characters far outside society’s margins. Counterculture, you say? Tod Browning, who claimed he’d left his Kentucky home as a teen to join a traveling carnival, knew what “dropping out” really meant.

But even before that watershed screening in Venice, there were those who felt a deep connection with Browning’s vision, who saw him as “a master of atmospheric chillers that aimed at far more than the superficial goose pimple,” as film historian Joe Franklin wrote in 1959. By 1968, Andrew Sarris had put Browning in the “Subjects for Further Research” section of The American Cinema, and observed, “The morbid cinema of Tod Browning seems to have been ahead of its time on some levels and out of its time on others.” That applies not only to the work but also to the man himself. Browning, born in the nineteenth century, was preoccupied with outcasts, grifters, the carnival life that thrived before movies. He began, so he said, by performing in the “carny” world that most solid citizens looked down on, and Browning in turn made movies that showed what his former cohort thought of its audience—necessary, sure, but also full of “suckers.”

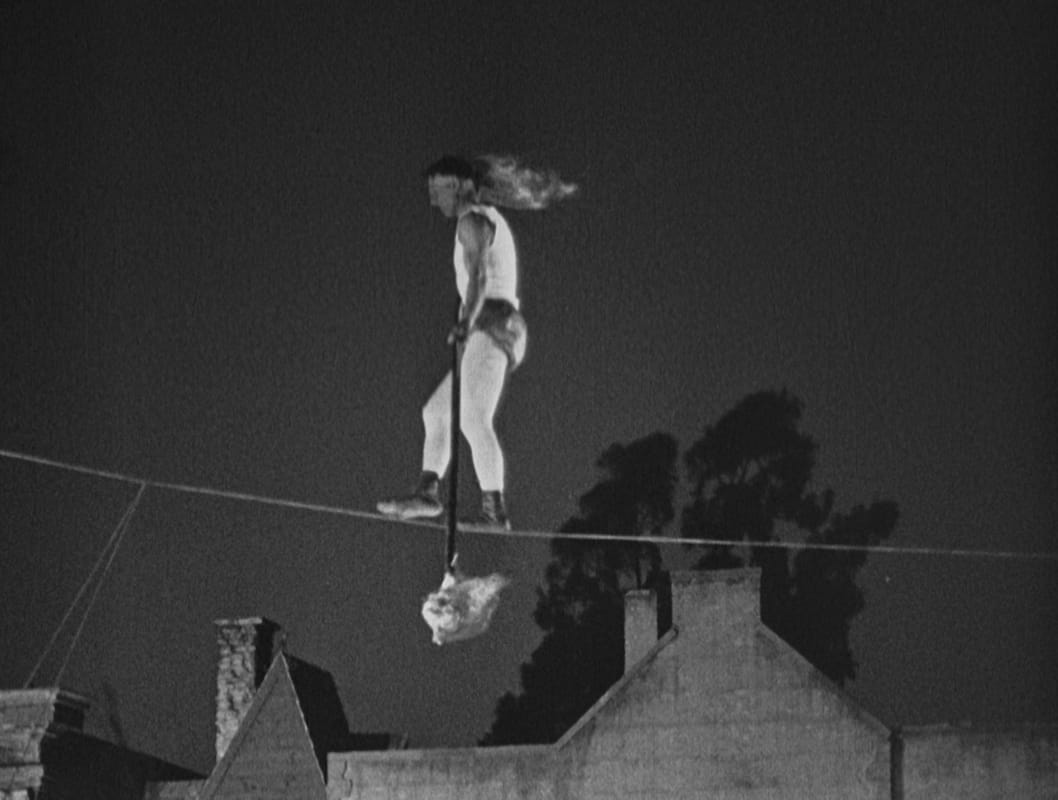

Freaks was far from the only time that Browning had put the world of the traveling carnival on-screen—it was just the most provocative. The circus, both home and hideout for a mix of society’s castoffs, is present in several entries from Browning’s extraordinary ten-film partnership with Chaney—in particular their greatest and most disturbing achievement, The Unknown, from 1927. Even Browning’s non-Chaney silents showcased his peculiar interests, such as the exposé of phony spiritualists wrapped up in 1925’s The Mystic. Over the seven-year period covered by these three films, it’s possible to see Browning gradually bringing in more of the personal obsessions that came to define his filmography. Browning knew he was pushing the limits of his era’s taste, as some critics compared his work to autopsies and the Spanish Inquisition. He was, quite intentionally, never a favorite with the squares.

Freaks

The Mystic

The Unknown