RELATED ARTICLE

Cure: Erasure

Share

Films about serial killers often combine the police thriller with the horror film. In his tense and atmospheric Cure (1997), Kiyoshi Kurosawa deepens the implications of this hybrid genre. Discarding the reassurances typically associated with the police in such films, he widens the social, political, psychological, and metaphysical issues surrounding random violent death and, in so doing, brings out the full irony and ambiguity of his deceptively simple title.

Born in 1955, Kurosawa belongs to the generation that came of age in Japan at a time when the collapse of the student political movements of the sixties and early seventies had left young people with the sense that their identities were, in his words, “uncertain and indefinite.” Having been marked by the American cinema of the seventies, and having honed his craft as a director of low-budget and straight-to-video movies beginning in the eighties, Kurosawa was, by the late nineties, well versed in the strategies by which a filmmaker can challenge producers’ and audiences’ expectations while playing at satisfying them. He brought to Cure, the film that won him international attention and set the pattern for his subsequent career, a sense of the contradictions within Japanese society and a confident understanding of how they can be addressed within genre cinema.

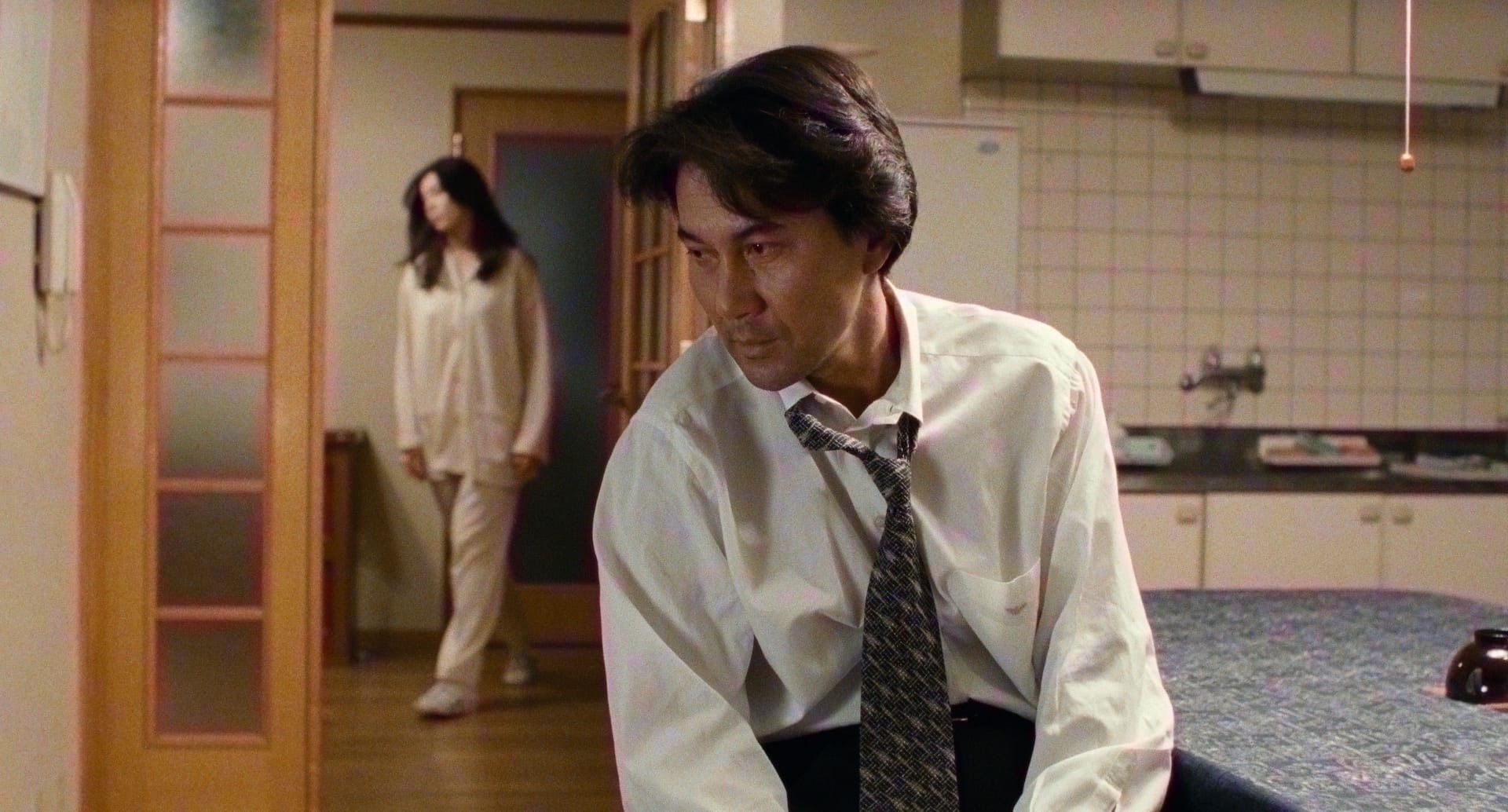

Committed by different people, the killings in Cure are linked only by slashes in the shape of an X across the neck of each corpse. The film hints that long-festering resentments figured in the background of at least two of the crimes. Surfacing among people who seem to be model representatives of their society (a schoolteacher, a police officer, and a doctor among them), this resentment assumes the dimensions of a social problem, albeit one that the film refuses to identify and that the detective in charge of the case, Takabe (Koji Yakusho), declines to explore. Takabe determines that each killer had been hypnotized during an encounter with a former psychology student, Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), whose own motives remain unknown. To the extent that viewers wish to see Mamiya punished, the film diverts the audience from the search for a “cure” and into the desire to see unleashed the vengeful police power that has been a traditional component of serial-killer films since Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry.