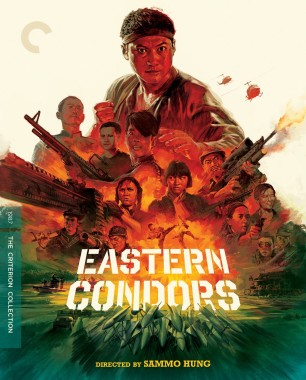

Eastern Condors: Collective Action

In the 1980s, Sammo Hung became one of the unlikeliest heroes in global action cinema. The genre was at the height of its beefcake era, with muscular hunks like Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Carl Weathers, and Dolph Lundgren pumping and juicing their way to Hollywood success. Over in Hong Kong, the similarly buff Jackie Chan built on Bruce Lee’s iconic displays of speed and power to become arguably the biggest movie star on the planet. Hung was the only figure standing athwart this onslaught of toned abs and bulging biceps. With his puddinglike physique, he used his uncanny athletic abilities to become an era-defining director, choreographer, and actor. But while most action movies are paeans to individual stars and their outsize egos, Hung excelled at ensemble pictures. His generosity of spirit, rare in Hong Kong and almost unheard of in Hollywood, was his secret weapon.

Eastern Condors (1987) represents the peak of Hung’s commitment to collective filmmaking. And along with John Woo’s Bullet in the Head, Tsui Hark’s A Better Tomorrow III: Love and Death in Saigon, and Ann Hui’s Vietnam trilogy, it is one of the few Hong Kong movies that deal directly with the Vietnam War. Hong Kong had held an uneasy position during the conflict because of both its proximity to the bloodshed and its status as a British colony neighboring China, an identity that linked it to two nations with competing interests, ideologies, and allies. During the war, it had been an R-and-R destination for American servicemen, and later it became host to hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing the new regime. Eastern Condors’ narrative of masculine heroism at times calls to mind the Rambo films, the first of which was made five years earlier, but where Stallone essentially plays an avatar of Reaganite individualism, Hung brings together as many friends as he can, casting old classmates, other members of Hong Kong’s illustrious stunt community, fellow choreographers (Yuen Wo-ping and the late Corey Yuen), and his future wife (Joyce Mina Godenzi). Taking inspiration from Hollywood “men on a mission” movies like The Dirty Dozen, as well as from homegrown ensemble actioners like Wong Jing’s Mercenaries from Hong Kong, he crafted his own inimitable approach to the genre.

Hung’s sensibility was forged in a vibrant show-business milieu. His grandmother Chin Tsi-ang was one of China’s first great female action stars, and his grandfather Hung Chung-ho was an accomplished director, first in Shanghai and later in Hong Kong. Both of his parents worked in the industry as well, in the wardrobe department. At the age of nine, Hung was sent to the China Drama Academy in Kowloon, where he studied Beijing opera and learned kung fu, singing, dancing, and acrobatics. He became “big brother” to the school’s star troupe, the Seven Little Fortunes, whose members included Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao, Yuen Wah, Corey Yuen, and other future action luminaries. As a teenager, Hung gained significant weight after an injury prevented him from exercising for an extended period; upon getting back on his feet, however, he found that he could still maintain his acrobatic skills.