RELATED ARTICLE

It Happened One Night: All Aboard!

The Criterion Collection

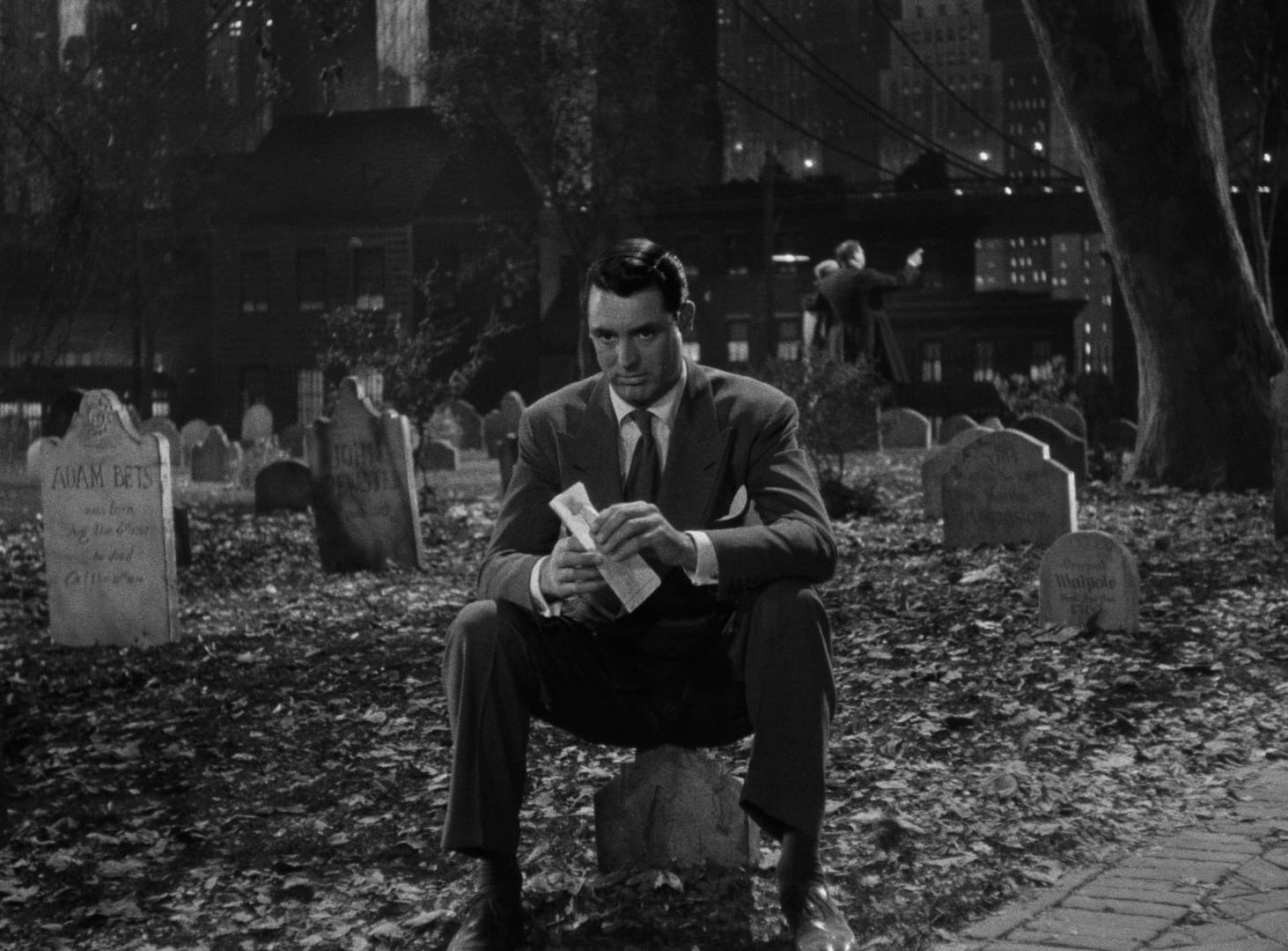

Arsenic and Old Lace, the best film ever made about the construction of the Panama Canal, was shot in 1941 but then laid down, like a fine wine or an expiring body, for three years, until the source play finished its Broadway run. Warner Bros. fretted about backing a film they couldn’t immediately profit from, and director Frank Capra would grouse about missing out on three of the war’s box-office boom years, but in 1941 absolutely nobody worried that the film would age badly or that audiences would lose interest in Cary Grant, and such complacency was fully justified, it seems, because here we all are.

Grant had only recently solidified his star status. He likened the Hollywood pantheon to an overcrowded streetcar: “It took me quite a while to reach the center . . . Then Warner Baxter fell out the back, and I got to sit down.” The actor was taking a break after his first Alfred Hitchcock film, Suspicion (1941), and trying to marry socialite Barbara Hutton, which involved complex legal maneuvering to confirm that she was actually single, a situation that finds an analogue in Arsenic and Old Lace’s frustrated honeymoon.

Grant had been a freelancer since 1936 and would always remain one, enjoying his pick of projects from all the majors; Capra had recently ended his twelve-year alliance with Columbia—a studio he’d made respectable—and had tried his hand at independence with Meet John Doe (1941), but with war looming, he ducked back into the security of a studio project. He was drawn to the novelty of a movie without a message: during the thirties, he had become closely identified with a kind of populist social commentary. This time, he just wanted to have fun.

Capra would later recall that Grant “had a ball” on Arsenic. But his was a very creative memory. In reality, Grant fussed about the sets and costumes and quarreled with Orry-Kelly, his former roommate, now Warners’ chief costume designer. At the root of it was the star’s discomfort with his performance. But he was always prone to worrying: begging to be fired from The Awful Truth (1937), positively refusing to share screen time with a piglet in Operation Petticoat (1959), fretting that backlighting would make his ears glow while shooting The Grass Is Greener (1960).