RELATED ARTICLE

A Cantopop Dream Girl’s First Film Reverie

By Oliver Wang

The Criterion Collection

When Wayne Wang’s Chan Is Missing began to draw national attention upon its release in the spring of 1982, two important cinematic milestones were reached. First, as Wang’s solo debut film, Chan was instrumental in launching one of the more prolific and eclectic directorial careers of the past forty years. Wang’s independent films, such as Smoke (1995) and The Center of the World (2001), have often leaned more experimental than those of his contemporaries; his studio projects have rarely felt predictable, either, whether it was the Jennifer Lopez rom-com Maid in Manhattan (2002) or the gentle family melodrama Because of Winn-Dixie (2005). Second, on a larger cultural level, Chan became the first narrative feature made “by and about” Chinese/Asian Americans to gain widespread recognition and distribution—a genesis moment for an Asian American cinematic practice now into its fifth decade. Chan is more than just a first, however. Its enduring significance—and pleasures for the viewer—lie in how Wang distills a set of broad social themes through his intimate snapshot of San Francisco’s Chinatown neighborhood and its delightful panoply of personalities.

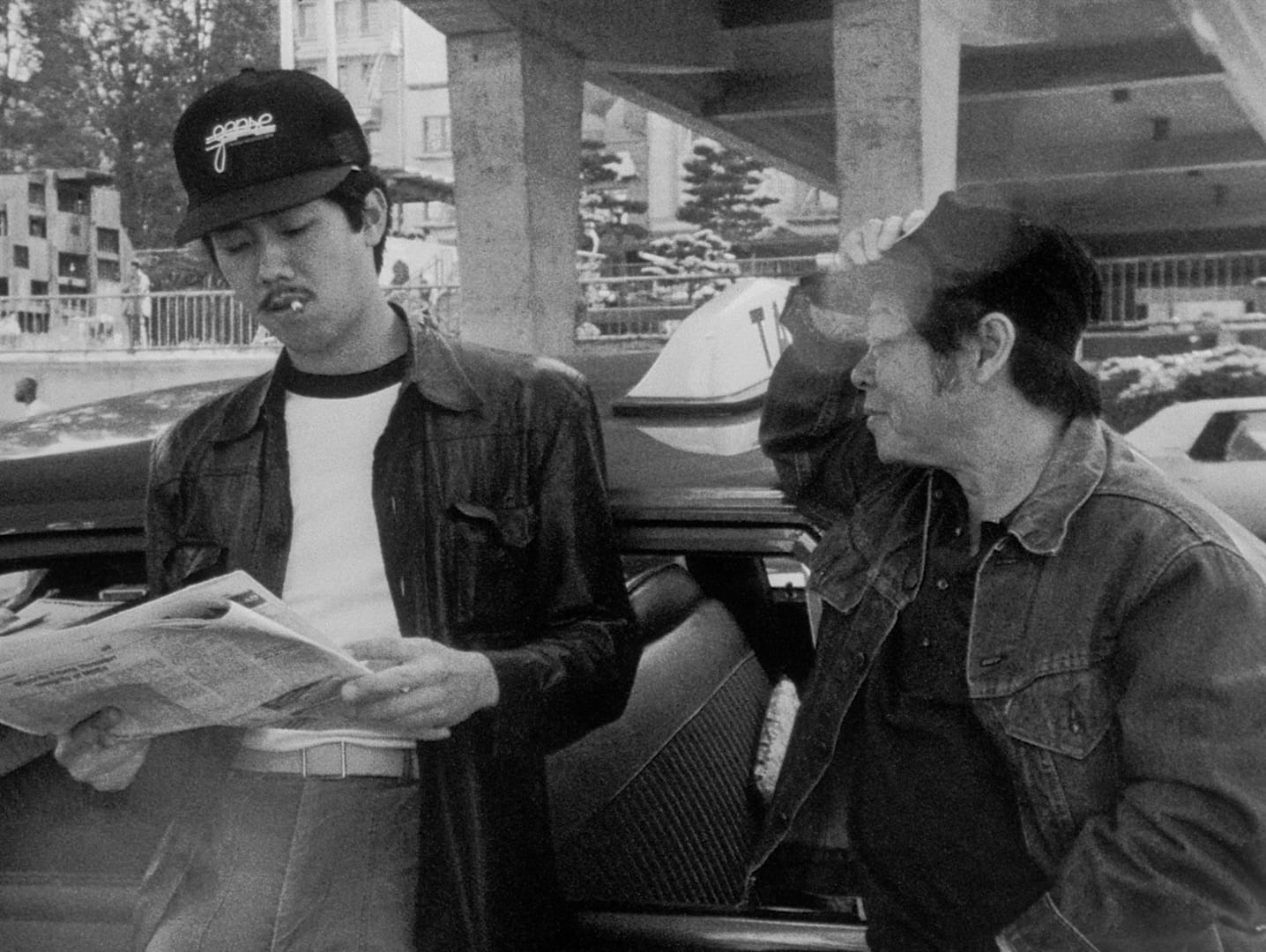

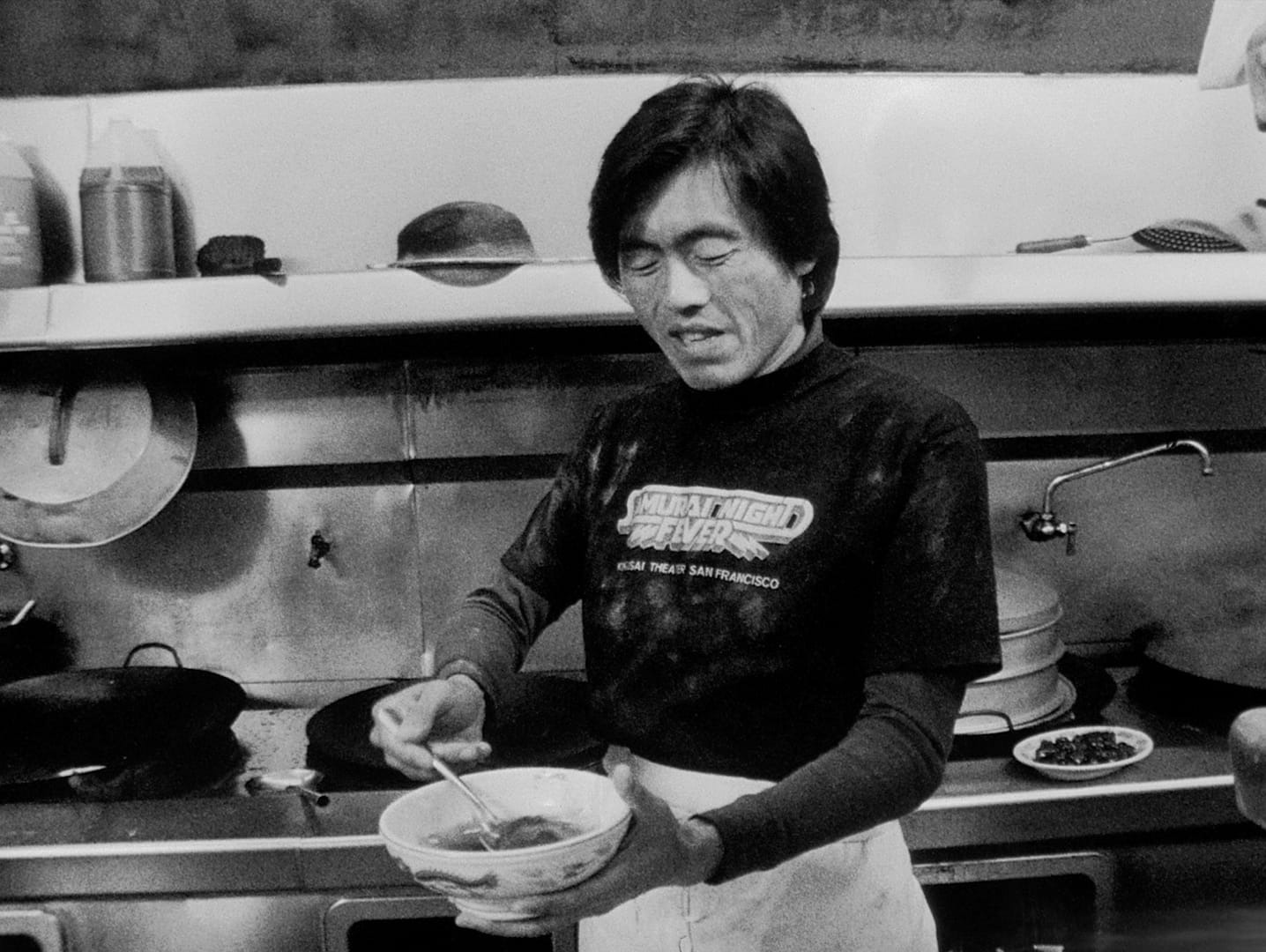

On the surface, the black-and-white film tells a simple story: Jo (Wood Moy) and Steve (Marc Hayashi) are a pair of Chinatown cabbies searching for Chan Hung, a friend who owes them money; a mystery (and hilarity) ensues. But atop that basic conceit are layers of complexity, whether in Chan’s genre-bending, its experimental storytelling, or its quirky but genuine-feeling characters. It’s no exaggeration to claim that American film audiences had never seen anything quite like Chan before, and even among Asian American films, few have resembled it since.

To properly put Chan into context, one must remember that, before the 1970s, the concept of “Asian American film” simply didn’t exist. Cast and crew members of Asian descent had been active in the movie industry since its inception, but it wasn’t until the Asian American Movement of the late sixties and early seventies that a socially committed, solidarity-driven, pan-ethnic ideal of Asian American–ness began to surge forth, especially in the realm of media arts.

One of the first narrative features to be informed by the movement’s

cultural politics—promoting community empowerment and amplifying the

voices of the marginalized—was Duane Kubo and Robert A. Nakamura’s Hito

Hata: Raise the Banner (1980). A story of the Japanese American

experience told through the memories of an aging immigrant laborer, Hito

Hata never achieved the national profile that Chan would enjoy two

years later, but the film’s focus on community history and social issues

helped influence an Asian American media arts ethos that has since

informed everything from Kayo Hatta’s Picture Bride (1994) to Gene

Cajayon’s The Debut (2000) to Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari (2020), as well

as several of Wang’s own post-Chan projects, such as the family

melodrama Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart (1985) and the historical

dramedy Eat a Bowl of Tea (1989).