The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum: The Past Is Present

The first European box-office success of the movement dubbed the New German Cinema, Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta’s 1975 The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum took on a hot-button issue: the paranoia provoked by homegrown terrorism and the opportunity that offered for mass surveillance by the state. At the time of its initial theatrical release, the film was regarded by some critics as too topical, and by the filmmakers’ more experimental cohorts as too closely wedded to old-fashioned social realism, stylistically, to have any lasting place in film history—a rush to judgment that proved stunningly incorrect. During the past forty-five years, worldwide government and corporate surveillance has proliferated unchecked. The information gathered, as Schlöndorff and von Trotta also foresaw, is often used by the “yellow press” to destroy the reputation of anyone who challenges entrenched systems of power. Back when The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum was first released by Criterion on DVD, in early 2003, eighteen months after 9/11, the United States was already engaged in unprecedented monitoring of its own citizens. Nearly two decades later, the term surveillance capitalism has common currency.

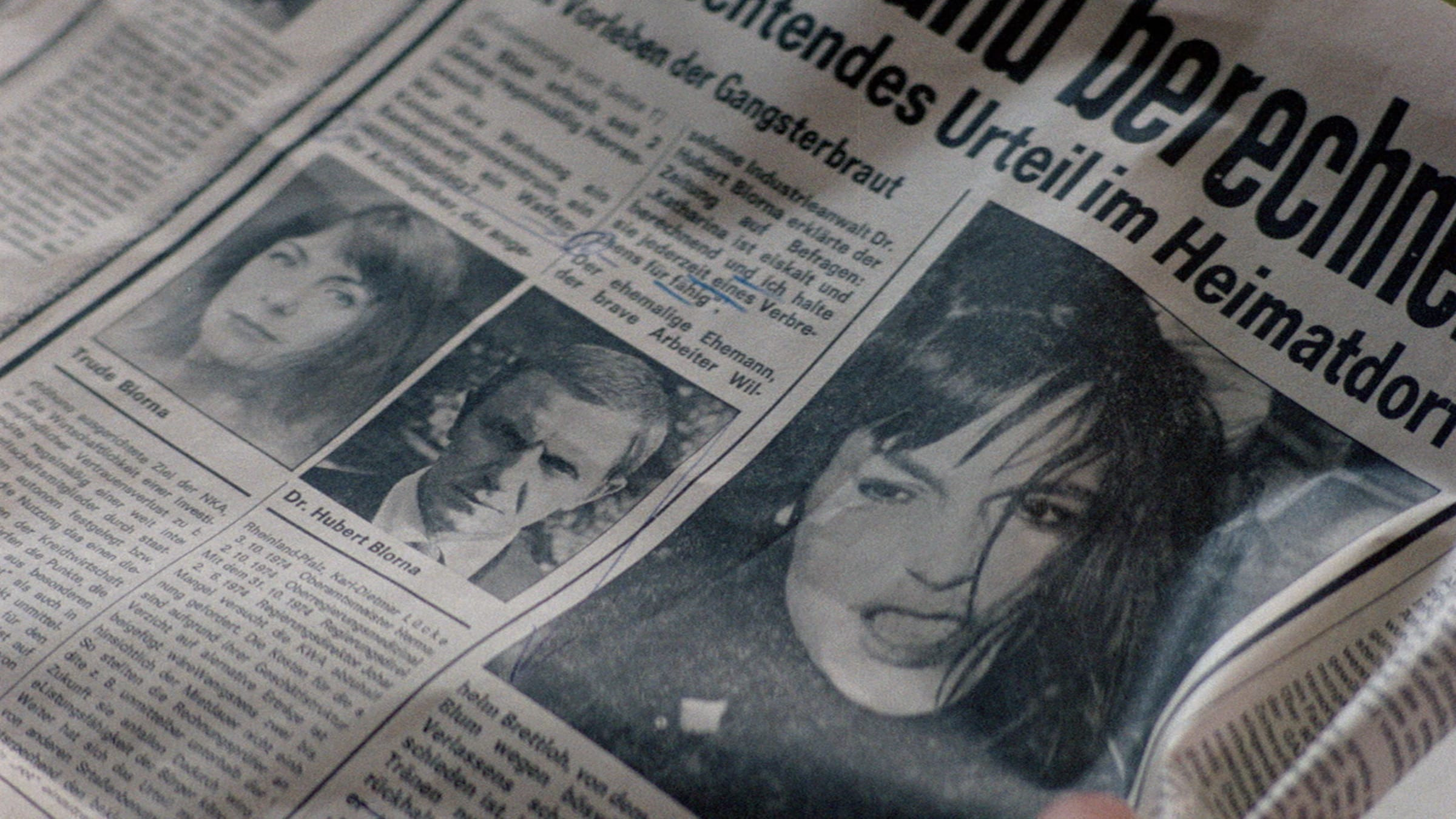

Schlöndorff and von Trotta’s film is adapted from the Nobel Prize–winning author Heinrich Böll’s novel of the same name, which is subtitled How Violence Develops and Where It Can Lead. Böll had been the target of a smear campaign by the Bild-Zeitung, the most popular daily tabloid in Axel Springer’s West German media empire. After he criticized the paper for stirring up mass hysteria with its coverage of the violent, leftist Baader-Meinhof Gang, the Bild-Zeitung retaliated by branding Böll a terrorist sympathizer. He and his family were subjected to police surveillance, searches, and wiretaps. Böll’s response was to write The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum. Schlöndorff and von Trotta end their film adaptation with a disclaimer based on the one in Böll’s novel: “All characters and events are fictitious. The descriptions of certain journalistic practices are neither intentional nor accidental but unavoidable”—Böll had named the Bild-Zeitung in his, and viewers of the film most likely would have understood the implication. Today, it is unavoidable that American viewers will analogize Springer to Rupert Murdoch, and the Bild-Zeitung to Fox News.

The New German Cinema was well underway when the film came out, having been launched more than a decade earlier, in 1962, with the publishing of the Oberhausen Manifesto, a proclamation made by a loose confederation of filmmakers and actors declaring their break from mainstream film production and distribution and also renouncing, as had the French New Wave a few years earlier, the classical forms of European art cinema—the “tradition of quality”—in both form and content. As in France, and in the United States with the emerging American independent film movement, this new cinema united filmmakers with very different styles and preoccupations, including artists with signatures as distinctive as the prolific, politically and formally radical Rainer Werner Fassbinder; the experimental team Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet; the unclassifiable philosopher-theorist-filmmaker Alexander Kluge; and the wildly different storytellers Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog. Women directors, for the most part, arrived later. It was not until the late seventies that von Trotta, Helke Sander, Helma Sanders-Brahms, and Ulrike Ottinger began to make significant work on their own, each of them as particular in her approach to film representation as her male colleagues. What they all shared was the desire to develop a personal film language, often tied to political issues.

Schlöndorff had studied at the Sorbonne in the late fifties and stayed in Paris to work as an assistant to prominent directors of the French New Wave, among them Alain Resnais, Louis Malle, and Jean-Luc Godard. He returned to his native Germany in the early years of the New German Cinema’s challenge to old-guard institutions—when the filmmakers were finding support from the country’s major television networks—and quickly made his mark with Young Törless (1966), based on the novel by the Austrian writer Robert Musil. His devotion to literary adaptations and a more realist style was evident from his early features, among them a made-for-TV version of Bertolt Brecht’s Baal (1970), which stars Fassbinder and, in a supporting role, von Trotta, who had also acted in Fassbinder’s Gods of the Plague (1969) and The American Soldier (1970).

“At every minute of the film, there are various possible interpretations of Katharina’s actions and character, but it is impossible to settle on any one of them as a representation of the truth.”

“The power and relevance of Katharina Blum today have everything to do with the linkage of a fact-free free press to surveillance capitalism. Whoever controls information also controls disinformation.”