RELATED ARTICLE

Now, Voyager: We Have the Stars

The Criterion Collection

Years ago I took a seminar on movie stars led by the writer Wayne Koestenbaum, a glittering episode that closed out a rather colorless stint in graduate school. The syllabus was replete with inspired double bills—Deleuze on Leibniz + Lana Turner in Madame X one week, Totem and Taboo + Trog another. Glamour, the course made clear, invites obsession, exegetical and otherwise. It was there that I first encountered the work of playwright Adrienne Kennedy, as visionary a figure as the American theater has ever produced. Her one-act A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White was a key point in the semester’s constellation. Here was a play where old Hollywood iconography commingled with experimental form: the main character’s life is articulated through the screen idols of her youth, featuring actors playing Bette Davis, Montgomery Clift, et al. As elsewhere in Kennedy’s dramas, the self is ever-shifting, an identity dispersed across multiple personages, who emerge out of the past onto the scene of the present. Naturalism is eschewed, yet the mechanics of psychic life are rendered with a powerful accuracy (one thinks of Cocteau’s own description of Blood of a Poet: “a realistic documentary of unreal events”).

When Jay Sanders and Hilton Als invited me and Ed Halter to organize a program in conjunction with the Kennedy retrospective they were curating for Artists Space, I was thrilled. We decided to arrange a suite of screenings that would highlight the many ways cinema had shaped her sensibility, bringing together, among other selections, a Dorothy Dandridge soundie, the Lon Chaney Wolf Man, a reel of Katherine Dunham choreography, Cukor’s Gaslight, some Astaire-Rogers toe-tapping, wartime propaganda, and, of course, a Bette Davis picture. Unfortunately the series was slated to run the very week the city began to close down in response to COVID-19, and is now postponed until it’s once again safe to host events. In the meantime, however, I had the chance to email with Kennedy about her lifelong cinephilia, and am looking forward to her latest collection of plays, which will be published this summer.

Perhaps we should begin from the beginning: How did your life as a moviegoer start? Are there certain early experiences at the cinema that have endured in your imagination?

I was born in 1931. I know that when my mother was pregnant with me she went to the movies once a week. My parents lived in Pittsburgh, where my father worked for something called Boys Club. He was a social worker. Although my mother had taught school in Florida, she did not teach now. She always said she was enraptured by movies and decided to name me, if a girl, after Adrienne Ames. Important that in the Georgia town where she grew up, and in Atlanta, where she went to school, blacks sat in a segregated section, but not in Pittsburgh. It was exhilarating for her not to sit in segregated seats.

Since everyone always asked me why I had such a funny name, I knew my name had import. As I got older I said I was named after a movie star, Adrienne Ames. They would always look puzzled. I was a tiny, pale child, very plain.

In ’35 my parents moved to Cleveland. My mother went to movies on Tuesday night, and took me. My father stayed at home with my little brother. We lived in a section of Cleveland called Mount Pleasant, then mostly Italian, black, and Polish. We walked to the movie theater called the Imperial on Kinsman Avenue. It was an old vaudeville house. I could sense this was important to her. We hurried . . .

And what was so astonishing to me is that she cried. She cried a lot. At the end sometimes she would say, “That was a good movie.” To see her crying was hypnotic to me. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. Why did that screen make her cry? What I remember is her saying she liked Back Street.

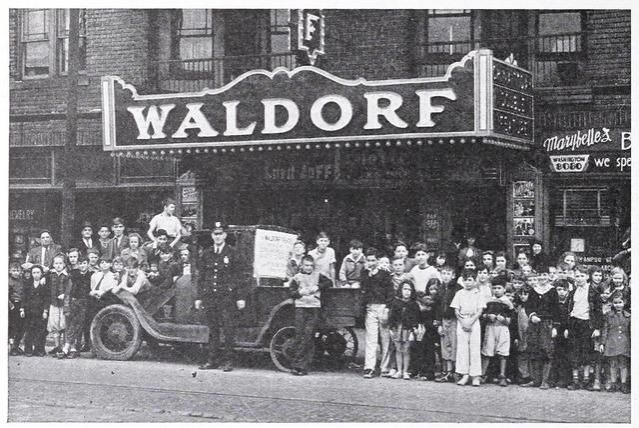

Days after a movie, my mother talked to me as an equal. She asked my opinion about actors’ clothes, their possessions, their choices. Kitty Foyle was to come. “I would like to have a suit like that,” she would say, and weeks later she would go to the May Co. and search until she found a suit like that. Those Tuesday nights were adventures. By the time I was seven I was allowed to go to the movies with the older girls next door. We went to the nearer Waldorf, Tuesdays and Saturdays.

I wanted to live in Paris and marry Fred Astaire. Forever I asked my mother, “Why couldn’t we live in Paris?” She said Paris was in Europe, and you had to go on a ship. I asked, “Could we get a ship from Lake Erie?” She explained you had to go to New York, get a ship, and go to Europe. “Could we do that?” I asked. She said “Adrienne, that is what rich people do. We are not rich. No. Your father makes a few thousand dollars a year at the YMCA.”

I still did not understand, and daydreamed a lot about the scenes, the staircases. To her credit, my mother never laughed at my questions. I knew in my heart I would dance with Fred Astaire. One day I would have dresses like that. But it was Jimmy Stewart in The Shop Around the Corner who became my friend. My imaginary friend. I really wanted to run away to Hollywood. I wrote a letter to him, and mailed it to Hollywood. I had seen Judy Garland writing to Clark Gable, so I knew it was possible.

The day I saw The Wizard of Oz is vivid. A friend of my mother’s, Virginia, took me downtown to the magnificent Loew’s State. Afterward we had a chocolate soda. I asked her many, many questions about Oz. All I remember was she smiled at me and said, “Adrienne, you are a funny child.” I was so baffled as to where Oz was. I wasn’t sure I wanted to go there.

I was dazzled by Tyrone Power, Black Swan; Rita Hayworth, dancing; Bette Davis, The Letter. But nothing captured as much as when, at eleven, I saw Now, Voyager. On a ship, transformed. I was haunted by ships crossing the ocean, and being transformed. So powerful is that theme that when I finally did cross the Atlantic, on the Queen Mary in 1960, I was determined I would be transformed.

Orson Welles follows, at age twelve when I saw Jane Eyre. Jane Eyre had been in my mind since I read the novel at ten or eleven. But this was the first time in my life that I had seen characters so important to me, a place so important—Thornfield—in a movie. Seeing Jane Eyre on the screen after being so attached to an old tattered library copy is a foremost experience. Edward Rochester was Orson Welles, and I would from then on be in love with Orson Welles.

There are too many others to name. The Red Shoes was to come. Lena Horne with a flower, Hedy Lamarr—people too beautiful. Although it was only one movie [Abbott and Costello’s Ride ’em Cowboy], Ella Fitzgerald singing “A-Tisket, A-Tasket” made me very happy.

Do you feel that your cinephilia has evolved over time—the way you see films, for instance, or the kinds of films that you’re drawn to?

I do not measure myself against the heroines, as I did in childhood and adolescent films. Elizabeth Taylor, in A Place in the Sun, was possibly the last heroine I measured myself against. I despaired over my lack of beauty compared to hers and, at age twenty, seemed to close this way of looking at heroines. A certain wistfulness passed. I was a college student, was soon to be engaged, and thought I was headed for a splendid life.

The movies then became mad clusters of intoxication—the Brando fixation, which included Kazan, the discovery of Sidney Poitier, Montgomery Clift. Living in New York, 1955, I was lost in foreign films for years: Bergman, Fellini, Antonioni. I was then trying hard to write stories. I remember studying Orpheus, Wild Strawberries, La dolce vita, The Leopard, trying to understand the statements they were making about the world.

I definitely felt a distance. It was not like the closeness of Mrs. Miniver or Gaslight, but it was a passion new to me. I wanted to be like the filmmakers. I wanted to create like L’avventura. I was now studying the images of La strada. I felt I was studying the world. I felt I was studying a society, something impossible in Notorious, Suspicion, The Lady Vanishes; the society was there, but I saw only the stories. No more buying spectator pumps because Bette Davis wore them in Now, Voyager. No more trying to do my hair like Paula in Gaslight. I wanted to know what Visconti thought of nineteenth-century Italy, what Rossellini thought of postwar Italy.

I watch some movies again and again. Even though I cannot define it I know those movies are healing me. I know when I see Wild Strawberries I am learning how to compose my disparate memories.

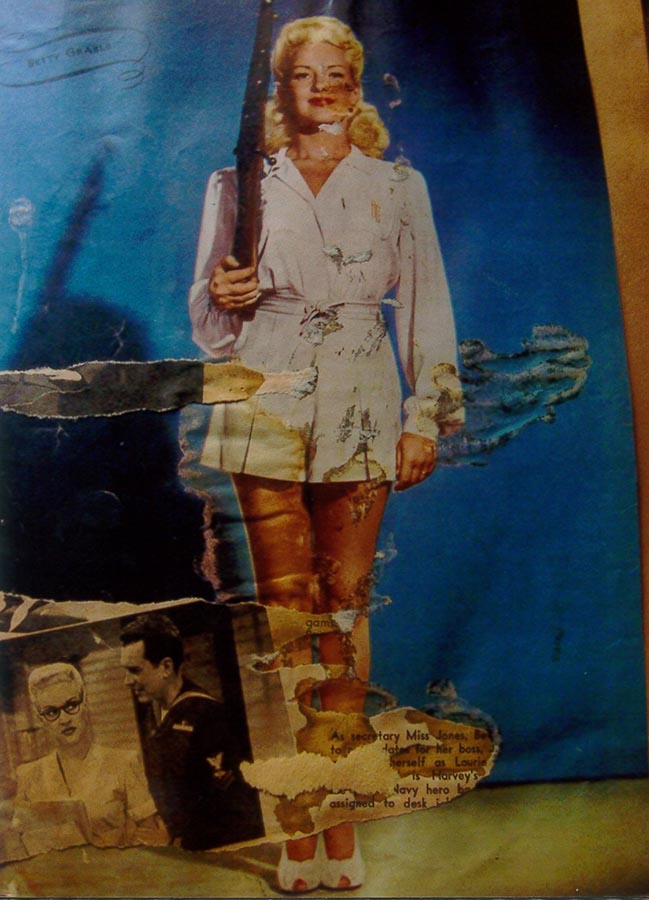

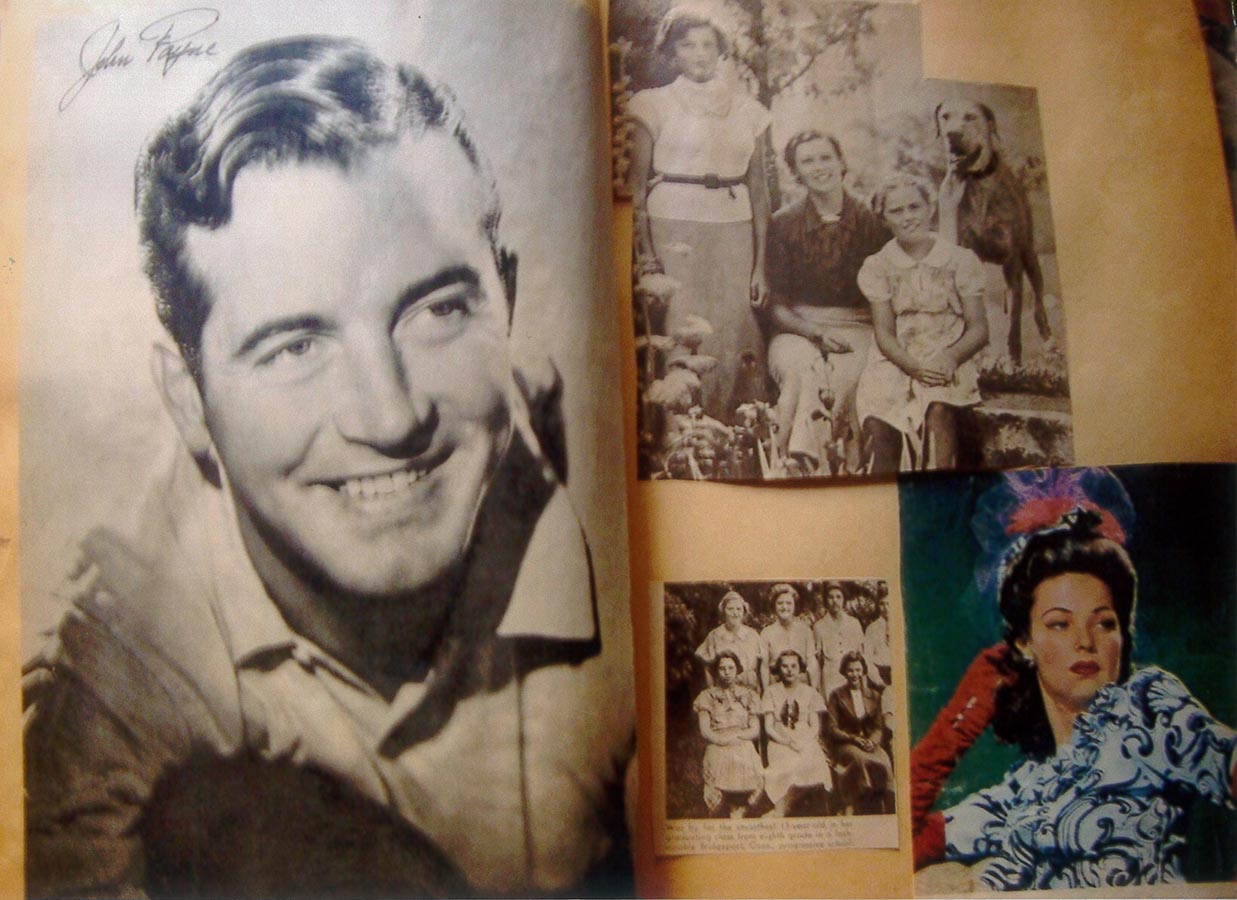

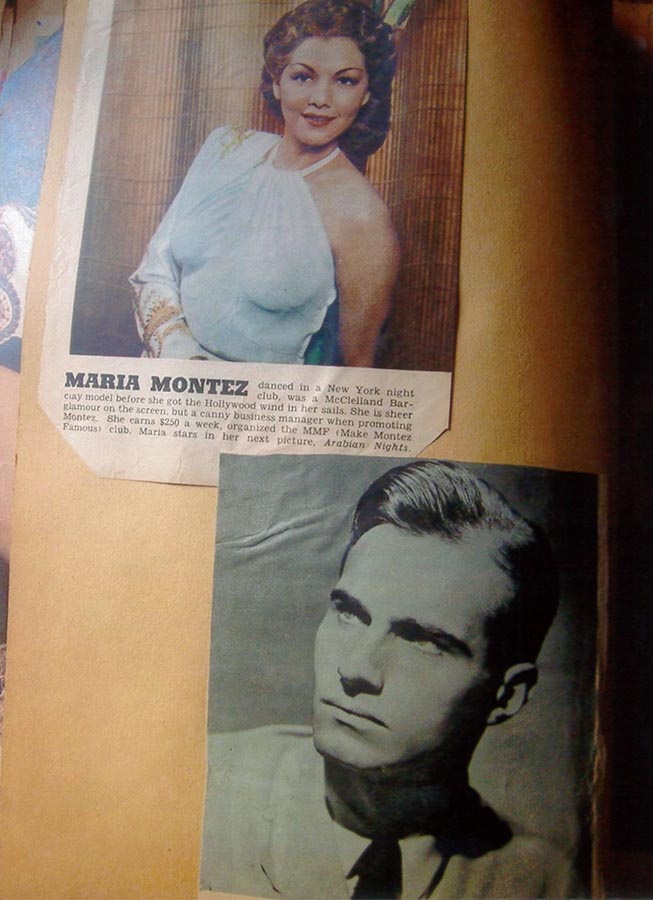

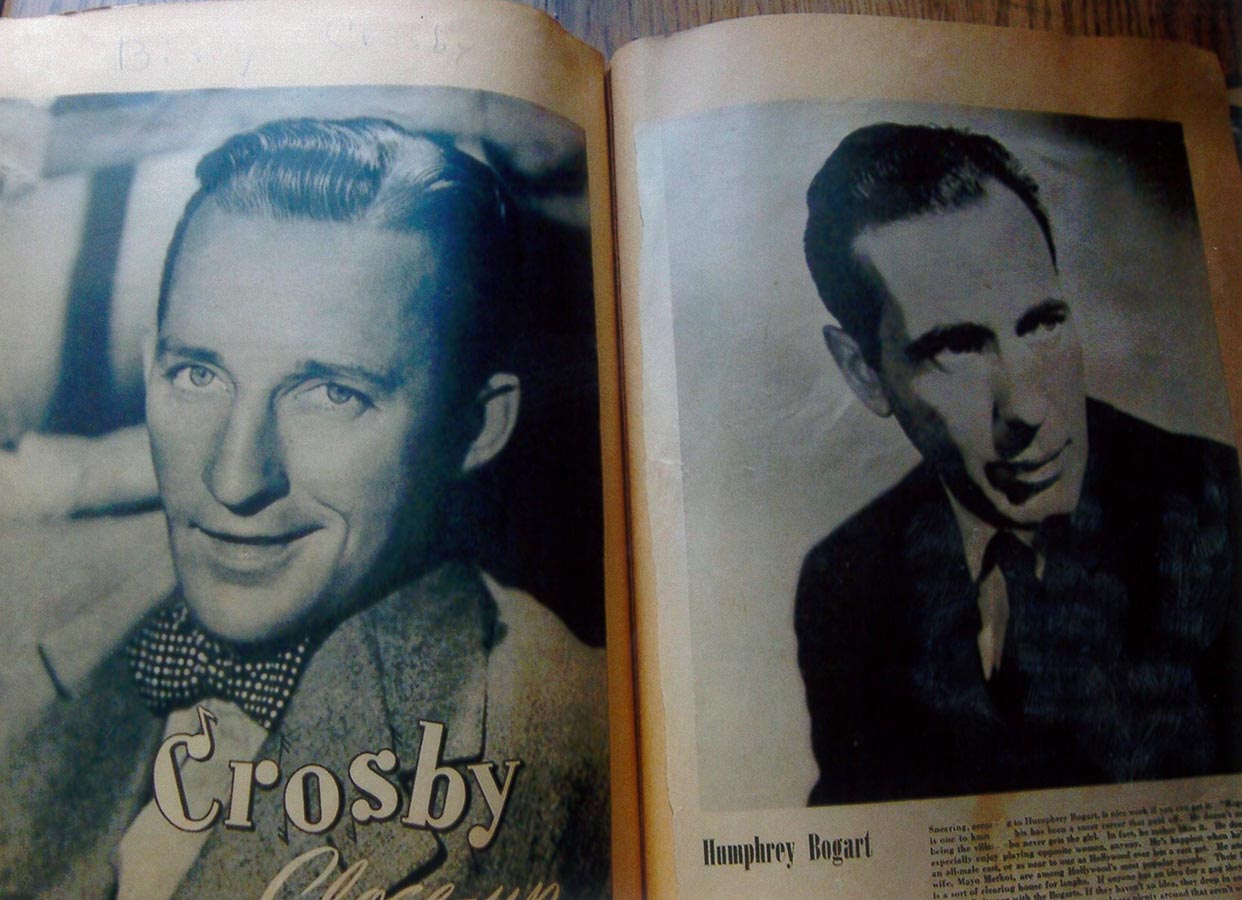

Photographs taken by Adrienne Kennedy of her homemade scrapbooks featuring movie stars. Courtesy Adrienne Kennedy.