Three Fantastic Journeys by Karel Zeman: Storm of Craft

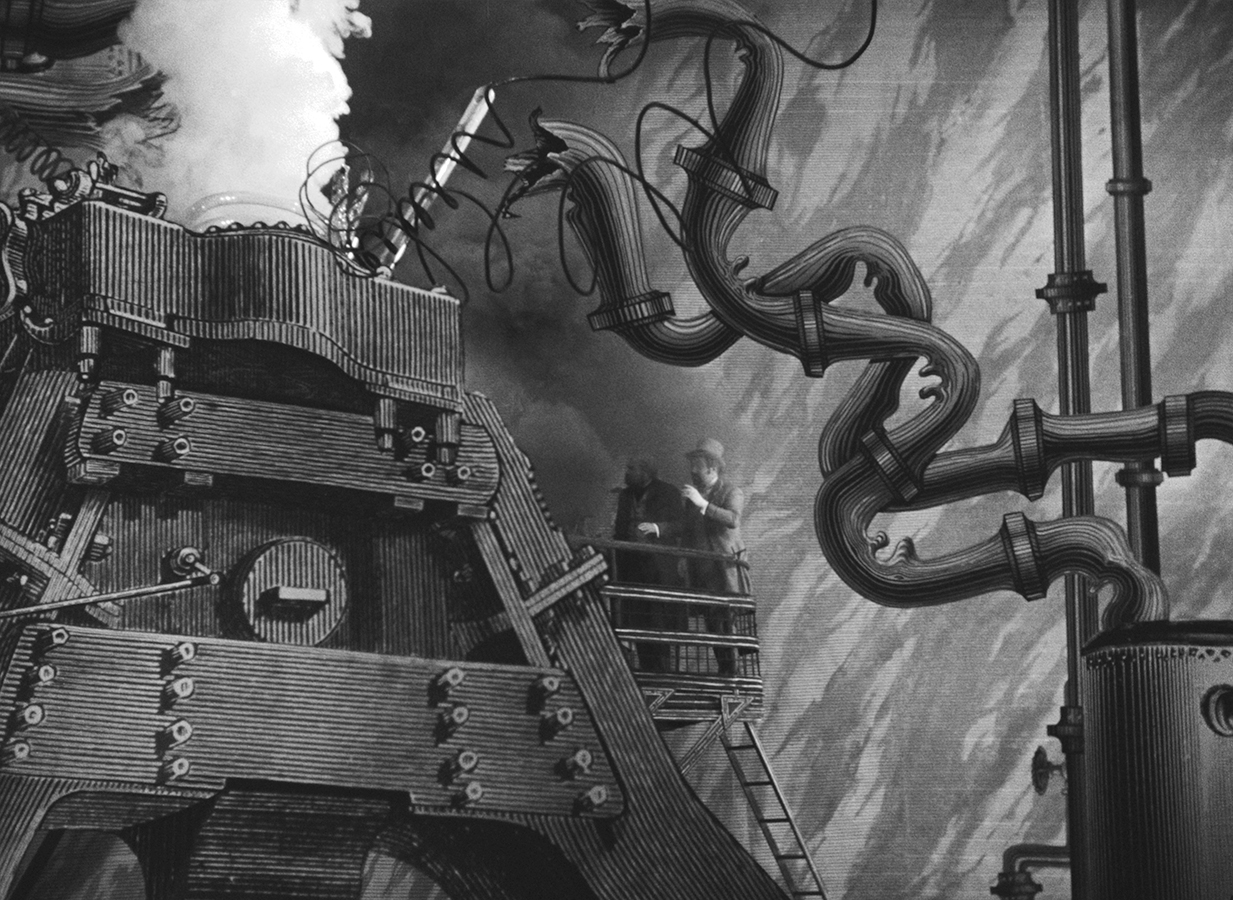

Karel Zeman belonged to an obsessive fringe fellowship of moviemakers that stretched right back to the medium’s first formative days—a lineage of auteurs who believed in cinema as a full-blown daydream machine, capable of realizing inhabitable fantasias. These were filmmakers—practical-effects adepts, animators of various stripes, and other hands-on world-builders—who thought of their movies less as stories than as objects, as handicrafts, as looking-glass manifestations of the bygone interior worlds of nursery fiction, Victorian illustration, puppet theater, snow globes, dollhouses, and other forms of child’s play. There had seemed something frivolous and guileless about film from the outset, but these artists took the association one step further, wholeheartedly embracing the medium as a window onto the energies of preteen naivete. First, Georges Méliès, within a heartbeat of the invention of the moving-image camera in the 1890s, brought to the screen a holistic attack of high-spirited fantasy, in his filmic equivalent of the nineteenth-century French theatrical tradition known as féerie, a mutt genre of fairy lore and stage gimmickry; Segundo de Chomón and other imitators turned this style into a subindustry in the early years of the twentieth century, just as Władysław Starewicz began animating rewired insect bodies frame by frame in what looked very much like unalloyed creative play. By the thirties, Walt Disney, Max and Dave Fleischer, George Pal, and Aleksandr Ptushko had anchored this tendency toward comprehensive retro artifice into the escapist moviegoing soil (it’s the handmadeness, the fingerprints and brushstrokes, that distinguishes these films from, say, studio genre product like The Wizard of Oz). Later, filmmakers as disparate as Jiří Trnka and Jacques Demy and Guy Maddin and Terry Gilliam and the Quay Brothers, among others more and less commercially known, expanded the mode’s ironic and formal parameters.

Born in 1910 in what would soon be called Czechoslovakia, Zeman was one of the legacy’s purest hearts, a melder of live action with all manner of animation who was, in the course of his three-and-a-half-decade-long career, perpetually agog at storybook fantasies, always hungry for new and recombinative visual techniques, and almost entirely unsullied by adult concerns. He was the real-life version of The Nutcracker’s Drosselmeyer, the exploding-toy-chest artisan who never forgot the buzz of a grade-school imagination passionately lost at sea. In a filmmaking career that began during the Second World War; overlapped with the Czechoslovak New Wave, as well as the Prague Spring and the subsequent Warsaw Pact invasion, in the sixties; and then pressed on through the dawn of the eighties (he died in April 1989, seven months before the Velvet Revolution began), Zeman remained surprisingly removed from political concerns, all but entirely sequestered from the totalitarian impulses and demands of the Communist state. A scan of his oeuvre for overt subversion is a waste of time, and not because he was anything close to a true believer—his heart was always in the impossible past. (The ruptures of the sixties impacted Zeman creatively only insofar as he started steering clear of Prague and stuck to his animation studio in Zlín, where he would be supervised less.) It couldn’t have hurt that the art and craft of puppetry was then, as it has continued to be, a primary, proudly self-identifying cultural tradition for Czechs and Slovaks going back centuries (it is one of the region’s few UNESCO-listed “intangible cultural heritages”), one that remained in favor throughout the Communist years. In time, the state’s largesse extended naturally to animated cinema, as pioneered by Zeman’s first film studio boss, the “mother of Czech animation” Hermína Týrlová—she helped produce his first short, 1945’s A Christmas Dream, a composite of stop-motion puppets and live action (with a dash of cel animation) that he codirected with his brother Bořivoj, released as Soviet and local Communist control took root. We tend to reflexively think of puppet animation as the isolated work of obsessive loners, but in Czechoslovakia, at least in the sound era, it had the prestige, bustle, and funding of a national enterprise, and like his contemporary Trnka, who created a national animation studio that is still operating in the Czech Republic, Zeman received generous state support for decades. Today, there is a Karel Zeman Museum in Prague.

“Zeman seems to have been as committed to graphic beauty as he was ardent for the days in which such craft mattered.”

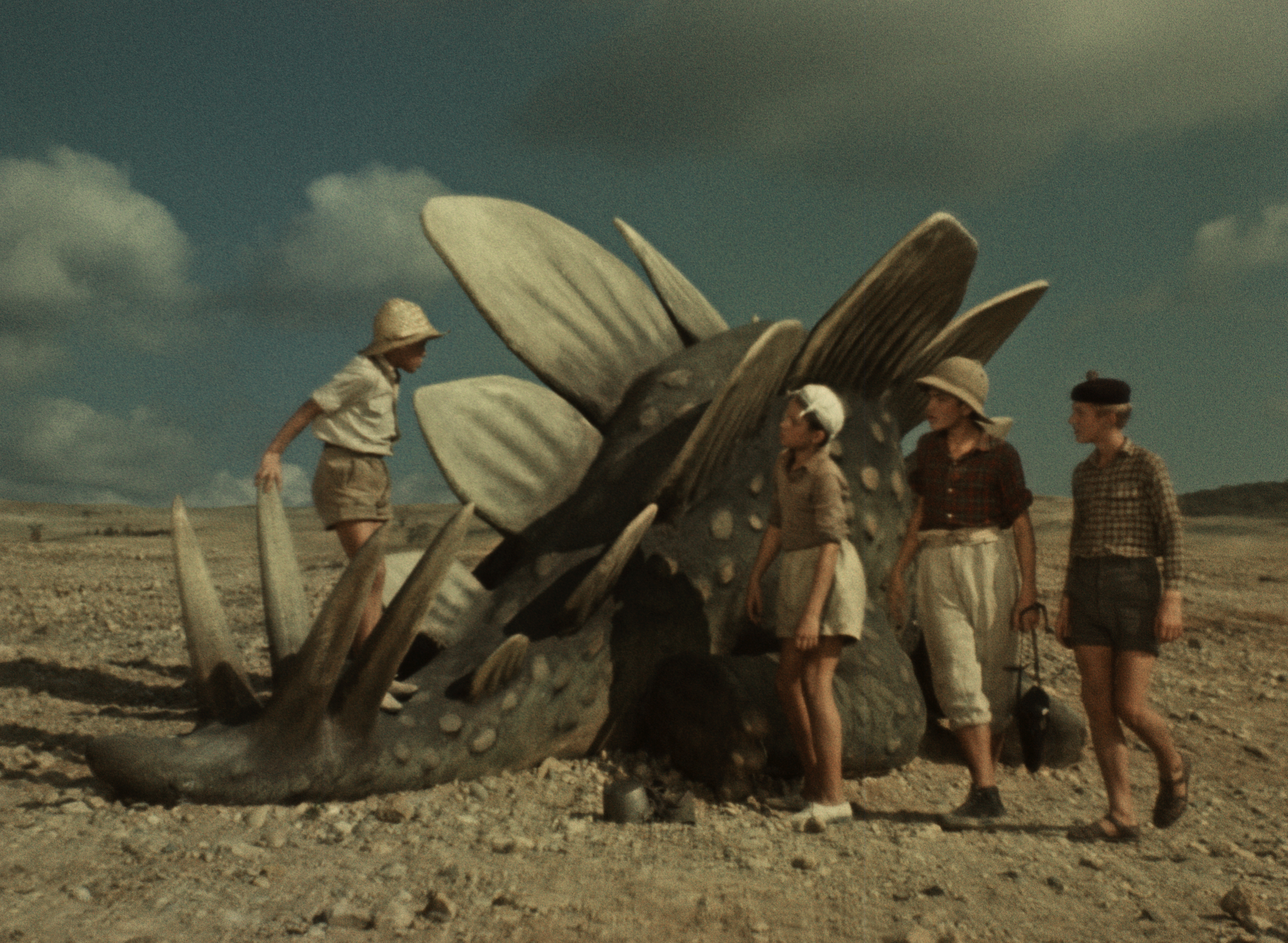

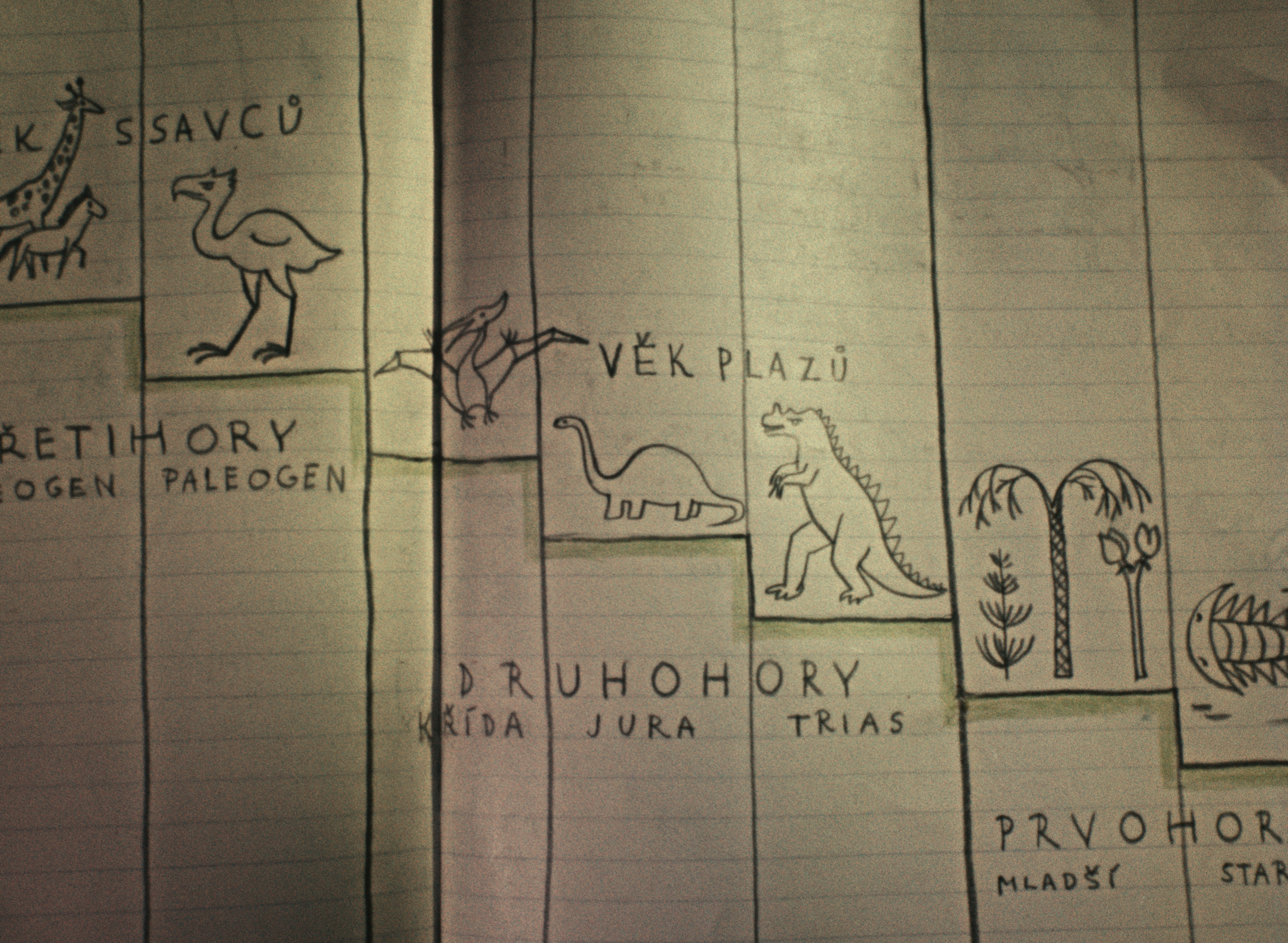

Journey to the Beginning of Time

“Part of all of his films’ pleasure is the palpable sense that Zeman, whatever his other aims and concerns, was manufacturing these head trips for the sheer love of it—they made him happy.”

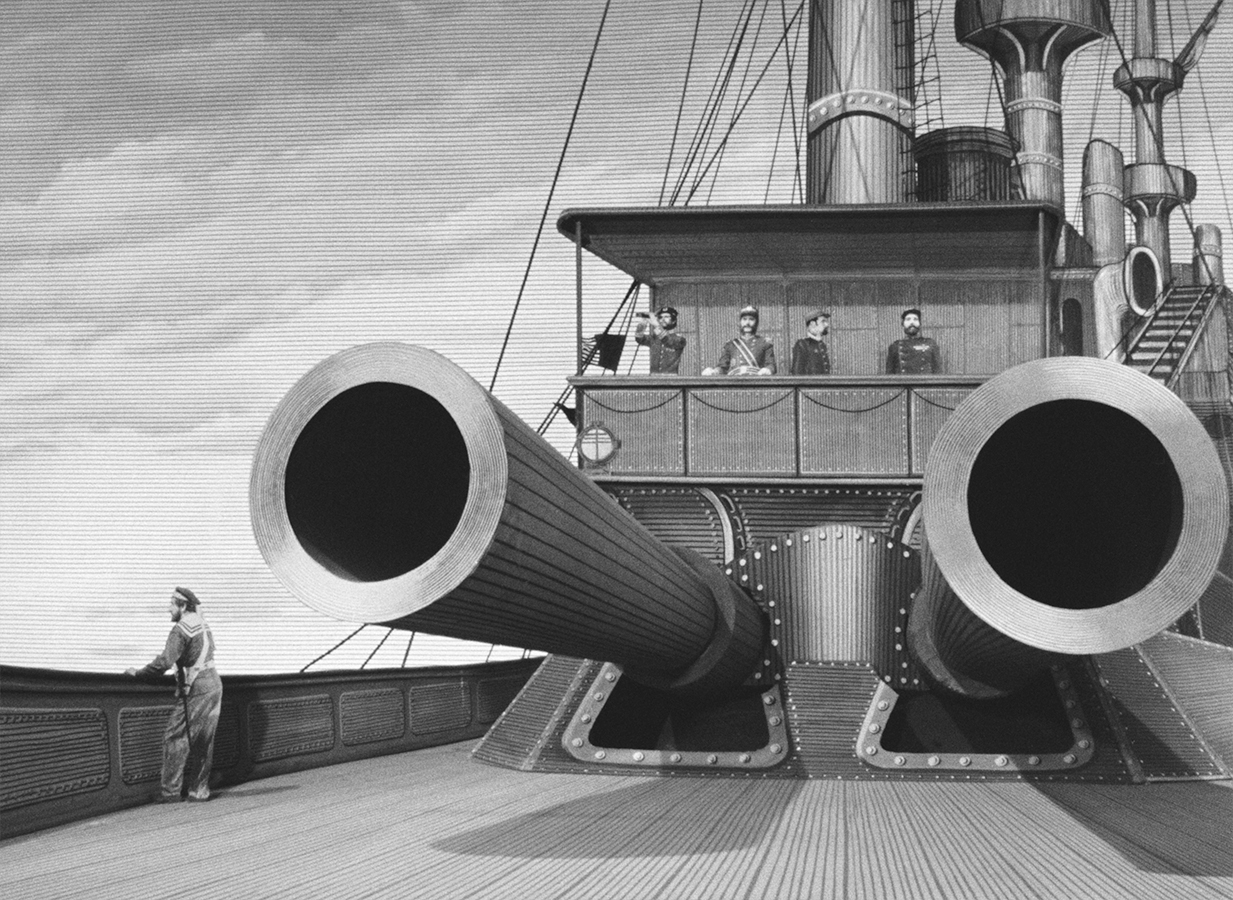

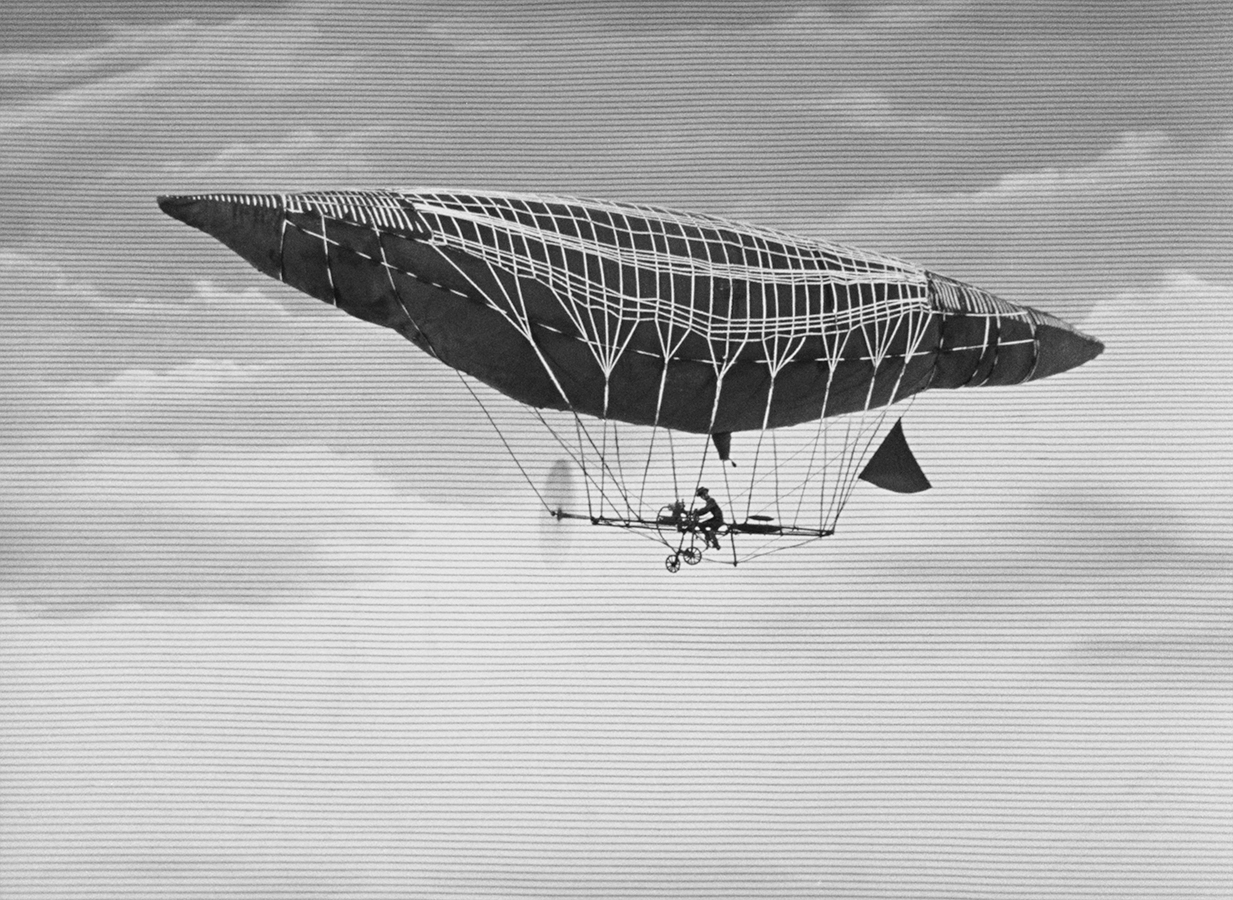

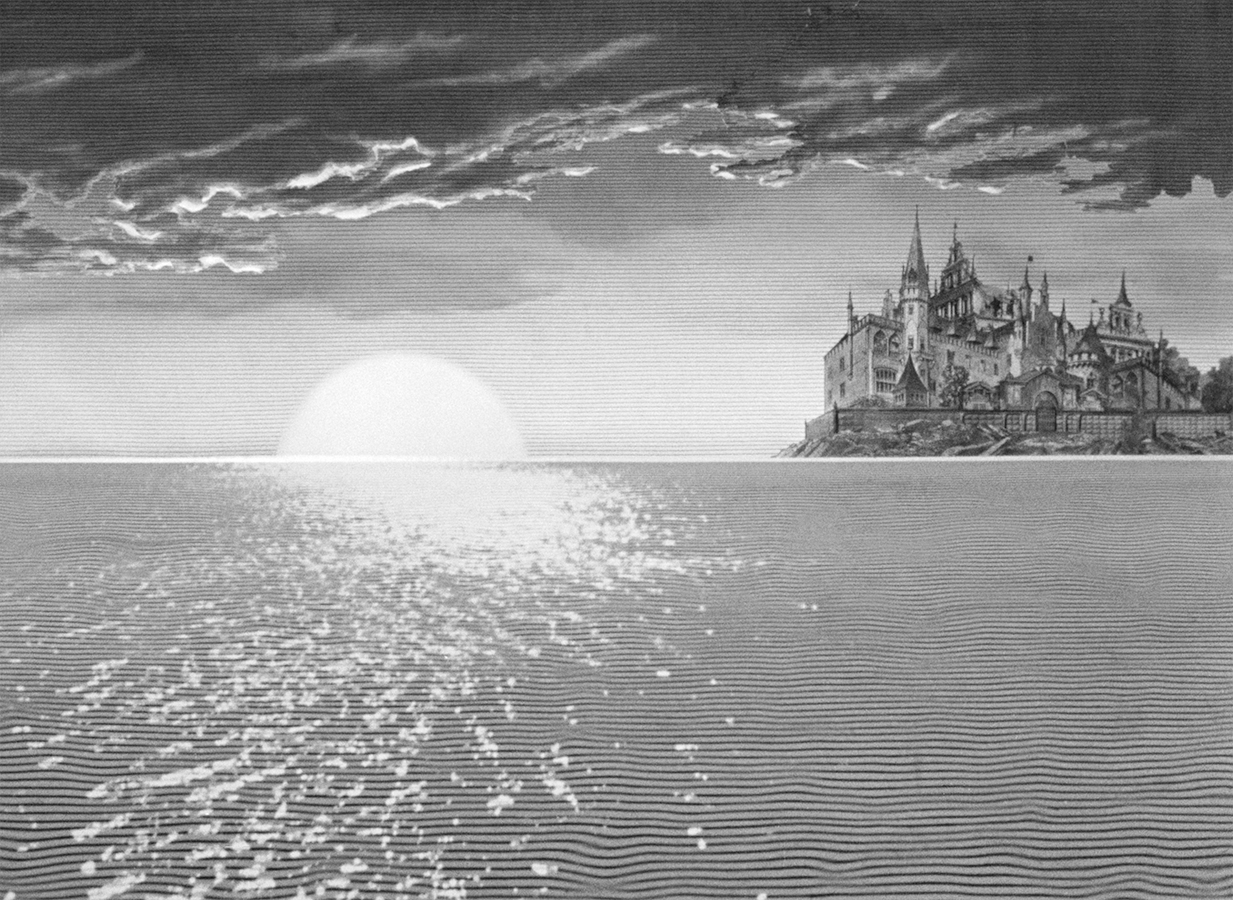

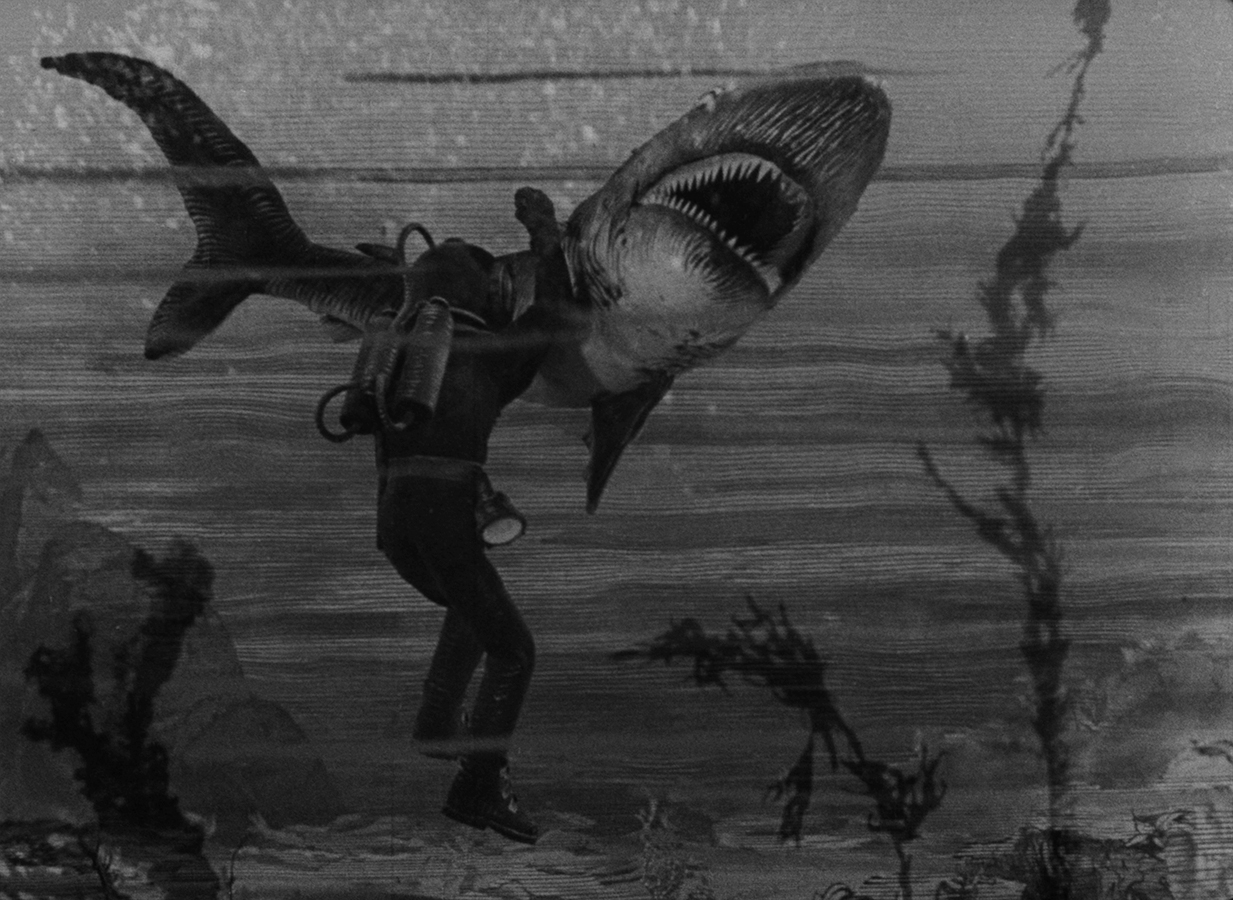

Invention for Destruction

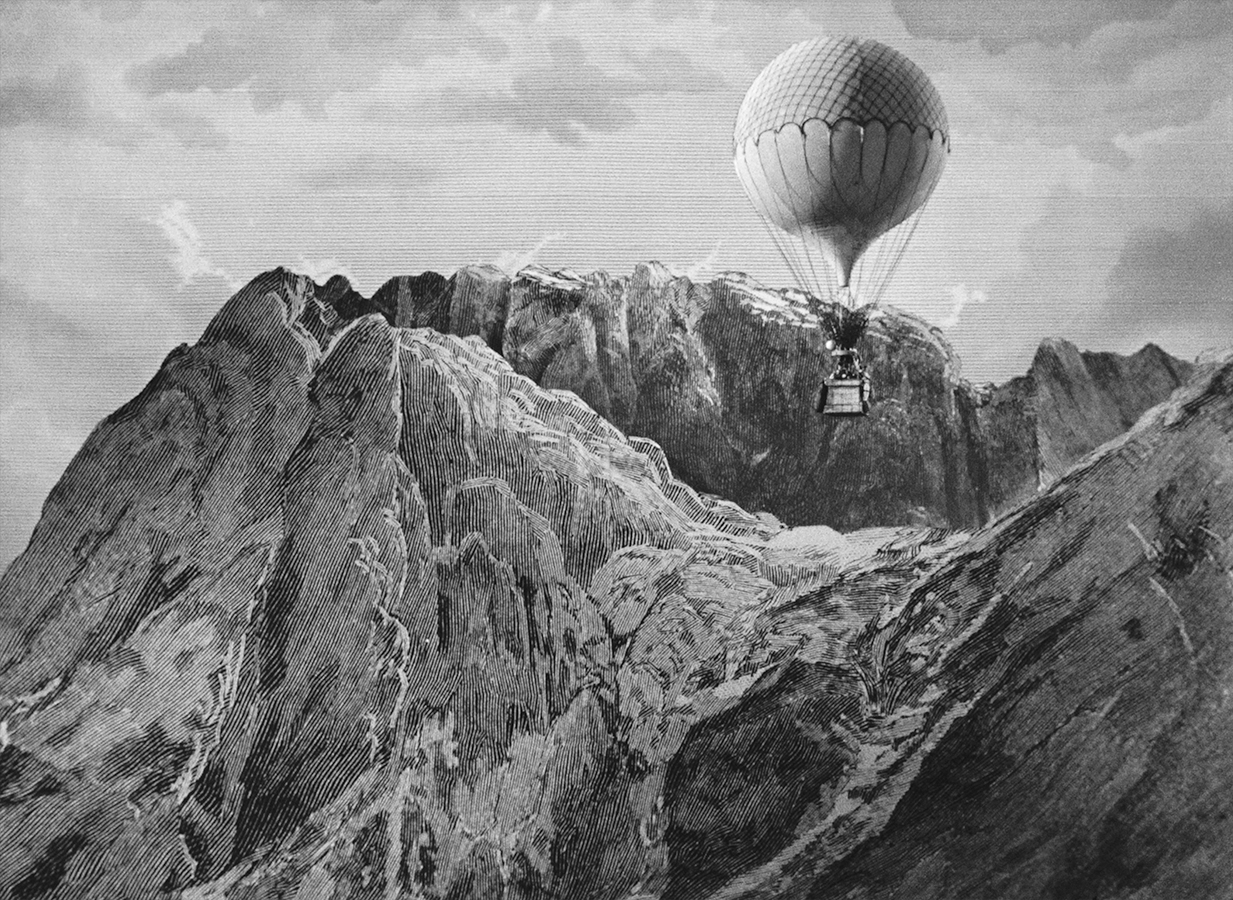

The Fabulous Baron Munchausen