Unlike directors of the so-called Left Bank New Wave such as Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, who were overtly politicized on the left, Godard’s Right Bank group, associated with Cahiers du cinéma, was only as political as the politique des auteurs, the auteur theory, whose fundamental defense of Hollywood filmmakers was found suspect by a French intellectual left that still looked to Soviet communism as a viable alternative to American-style capitalism. But, as Godard told Cahiers in 1962, his impetus for making Le petit soldat was a contrarian desire to issue a kind of corrective to his set’s apolitical image: “The New Wave is criticized for showing people only in bed; I’m going to show some who are in politics and don’t have time to go to bed.” Hiding behind this somewhat facile quip is the fact that the film is not so much a political statement as a self-portrait of the artist as an uneasy young romantic starting to see life beyond the movies and confusedly wondering where—if anywhere—his allegiances lie.

Le petit soldat undoubtedly had more personal resonance for Godard than Breathless did, beginning with its setting in Switzerland. Though born in Paris, Godard had spent his childhood and adolescence on the Swiss shores of Lake Geneva, the placid body of water to which he would return in middle age and that would come to be as closely associated with his later films as Paris cafés are with his sixties work. The film has further biographical significance in that it was Godard’s first collaboration with Karina, the young Danish model he’d sought out for the lead role of Veronica Dreyer after she turned down a supporting part in Breathless. By the time production wrapped in Geneva, Godard and Karina were a couple, and they married soon after. Their tumultuous relationship would result in one of the most fruitful creative collaborations in film history, yielding an iconic run of seven features: after Le petit soldat, they made A Woman Is a Woman, Vivre sa vie, Band of Outsiders (1964), Alphaville (1965), Pierrot le fou (1965), and Made in U.S.A (1966). In this film, Godard’s initial approach to Karina is stealthy. She is first seen in the distance of a wide shot, as if she were just another passerby picked out of the action in a street scene. Once inside Bruno’s car, she is filmed from behind or blocked by Bruno’s profile, glimpsed only for an instant reflected in her compact. It isn’t until Bruno parks the car and turns to say goodbye that Godard gives Veronica a close-up, as if we had to wait for Bruno to really see her—i.e., to fall in love with her—in order to be permitted to see her too.

Veronica is not Karina’s greatest part, just as Le petit soldat is not a high point in Godard’s depiction of women—in both cases because Bruno does nearly all the talking, some of which is fairly unenlightened. But it must be noted that, on one of the rare occasions when Veronica is able to get a word in edgewise, her statement on the Algerian War lands her squarely on the right side of history: “I could see the French are wrong. The others have an ideal, but not the French. Against the Germans, the French had an ideal. Not against the Algerians. They’ll lose.” This was one of the lines the censors found most objectionable, and it raises the very questions Bruno never resolves for himself: Can one live without an ideal? Is it possible to avoid taking sides? The evidence proposed by the film, which seems aware of the irony of tackling such questions in Switzerland, is that neutrality is an illusion: willing or unwilling, everyone is pulled into the conflict, and nobody comes out with clean hands.

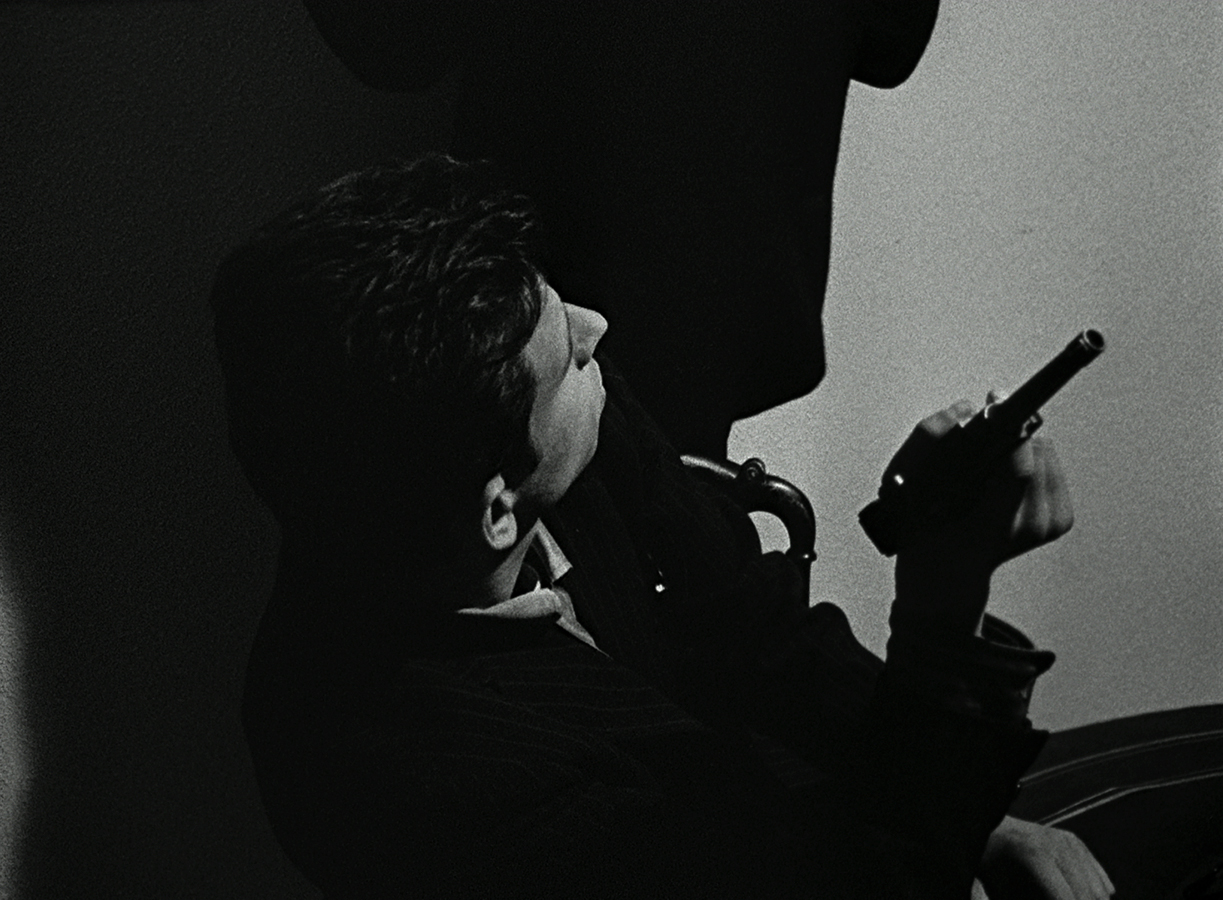

When it was eventually released, Le petit soldat elicited outrage over the apparent moral equivalence it draws between shadowy procolonial French agents and the Algerian “rebels” of the National Liberation Front (FLN), which seemed to many on the left as intolerable as the anti-French defeatism expressed by Veronica had to the censors. Key to Godard’s project and the controversy that dogged it was the extended scene in which Bruno is tortured by the FLN, a sequence distressing not only because it shows Subor actually being subjected to electric shocks and waterboarding but because of its muted, business-as-usual quality—while Bruno is tortured, people laugh and chat, the music picks up a little, and a woman in the next room reads Lenin and Mao. Most shocking, perhaps, is the fact that while the film makes it clear that both sides in the Algerian conflict use torture, as it was known that they did, only members of the FLN are actually shown perpetrating it, an artistic decision that was, to put it lightly, surprising to many. The documented use of torture by French forces in Algeria had been a galvanizing factor in turning public opinion in France in favor of independence, thanks notably to French journalist Henri Alleg’s terribly lucid account of his repeated interrogations by French soldiers in the 1958 book La question, an instant best seller that continued to circulate widely even after it was banned by the French government (and that Godard quotes in Le petit soldat). In a postwar France whose moral references were shaped largely by the trauma of the German occupation, many found it unbearable that French fighters who had in some cases themselves survived brutal Nazi interrogations were now turning these same methods against Algerians and their own countrymen. Whether Godard was reveling in being provocative or concerned that joining the chorus of French intellectuals decrying their country’s actions meant taking the easy route, his unpopular choice to emphasize torture by the FLN served his film’s fundamentally murky tone.

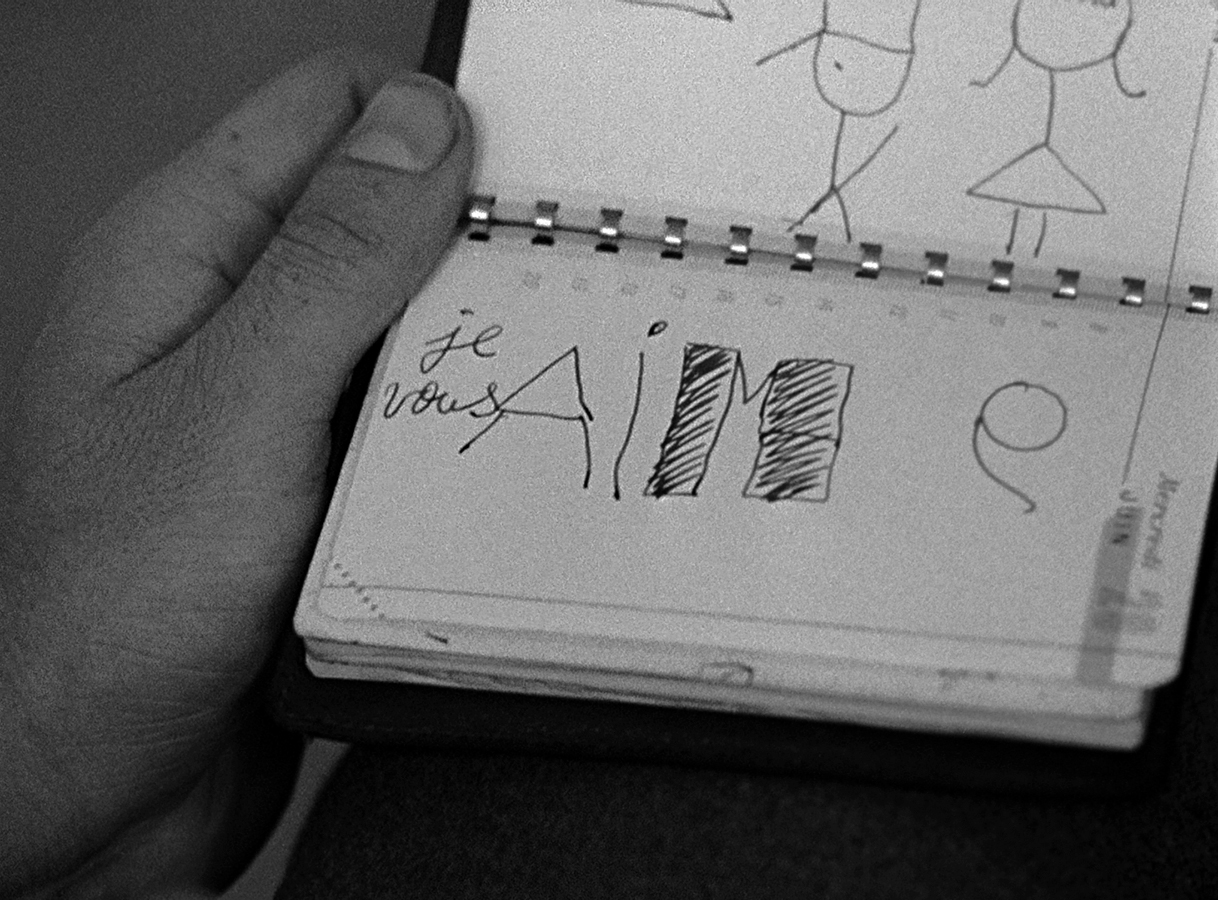

In the barrage of assertions spouted by Bruno in Le petit soldat, one of Godard’s most quoted epigrams stands out: “Cinema is truth twenty-four times a second.” Yet as is often the case with much-repeated lines, the quotation has entered the collective consciousness only in partial form. Bruno’s full statement as he begins his photo session with Veronica is “Photography is truth. Cinema is truth twenty-four times a second.” This nuance is crucial, because it draws attention to the fact that, in Godard’s mind, the truth delivered by cinema is not monolithic. Godard refers to the most basic principle of filmic illusion—the impression of fluid motion created by the projection of twenty-four still images per second—to underline the idea that truth is a constantly shifting notion. As Le petit soldat makes clear, Bruno’s epigram suggests not that cinema simply repeats a single truth but that it hunts truth down, frame after frame, as it evolves and occasionally escapes our grasp. This is rarely clearer than in Bruno’s final monologue, seven minutes of rapid-fire declarations that, for all their bluster, add up to little more than a penetrating record of a young man’s vacillation, a painful search for truth as he struggles with political engagement, freedom, and self-definition. The monologue culminates with Bruno telling Veronica that he yearns for the era of the Spanish Civil War, when there were worthy causes for young men like him to embrace. From our contemporary perspective, few causes’ worthiness seems as clear-cut as that of Algerian independence, but Godard, already a master of paradox, had the temerity to portray a man so overwhelmed by his ideas of the past that he is blind to the present. The result is an adventure film in which the protagonist yearns for heroism more than he embodies it. It isn’t pretty, but it feels like the truth.