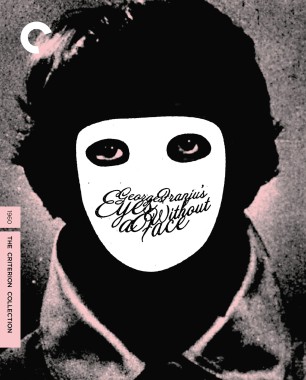

Appearances to the Contrary: Eyes Without a Face

Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960) is for me the most chilling expression in cinema of our ancient preoccupation with the nature of identity. Its core motif is the mask, here an uncanny thing of smooth, hard plastic worn by a young woman to conceal a face destroyed in an auto accident. Her name is Christiane; her father, Dr. Génessier, an eminent Paris surgeon, is obsessively engaged in an attempt to reconstruct that face. But his cosmetic project is a travesty of the impulse to heal, and Christiane, despite her disfigurement, remains in possession of what her father has lost, if he ever had it—a spiritual faculty, an idea of the good: a soul. Christiane will come to play moral antagonist to her monstrous father, a good woman pitted against an evil man.

What is remarkable about the film is not its thematic originality, for this is a familiar tale, but rather its imagery, its atmosphere, and the perfect rightness of the story’s narrative elements—the face and the mask, the graft and the wound, and later on, the dogs and the doves. In the first scene, we see a beautiful woman with a pale, waxy face driving a car through the darkest of nights. Night or dusk, deep shadow, roads wet with rain: these will be the features of this world, all implicitly negating what is clear, what is properly lit. There is almost no illumination but the sheen on the skin of the woman’s face.

She touches the rearview mirror, and we see that in the back of the car slumps a figure in a large overcoat, hat pulled low, limp and floppy as a rag doll. It is, of course, a corpse, which accounts for the waxy-faced woman’s anxiety as she drives: she is engaged in a clandestine act of body disposal. When at last she stops the car and steps out, her coat gleams against the blackness of the night, for it is made of a hard, shiny, reflective material. It is this feeling of hardness, of impenetrability, of the unnatural and inorganic—the synthetic—that will characterize all that is associated with Dr. Génessier and his grisly project. The woman is his assistant, Louise, who represents his success: she has emerged intact from his surgery. But like Génessier, she has no soul. Her function is to lure young women to the clinic outside Paris where he performs his ghastly surgical experiments.

The imagery and language of the clinic are a staple of the mad-doctor story, and Franju milks it for all its inherently sinister potential. There are numerous examples of medical jargon masking extremely nasty realities—the “heterograft,” for example, which translates as the attaching onto the patient of another’s skin. Which spells death, of course. More horrifying by far, however, are the vivid instances when we see Génessier at work. Surgical clamps proliferate. In one gloriously horrible scene, the doctor first marks the outline of the face, makes his bloody cut, then secures the incision with a forest of clamps—at which point comes, literally, the face-lift.

This is Franju’s heart of darkness. The film builds to this glimpse of monstrosity, this perversion of Western science—or perhaps the logical outcome of that science, a meddling in mysteries that ought to be the preserve of God alone. But having meddled, the scientist must be punished, and punished he will be.

It is a mark of Franju’s diabolically inspired storytelling that he should place a family at the center of the horror. There is a wonderful dinner-table scene, an exquisite instance of what might be called the “domestic perverse.” The doctor sits with two women, Louise—a kind of surrogate wife and mother—and Christiane, the three eating together as a family. All is harmony and love. But this must be one of the weirdest meals in the history of cinema, because each of the beautiful women has had her face dramatically altered by Génessier—in Christiane’s case, entirely replaced. A little later, outside the house and out of earshot of Christiane, things once again turn dark as the doctor tells Louise that, appearances to the contrary, he has failed another time.

Soon enough we have a lurid montage of decay, also glossed with medical terminology that can barely do justice to the images of organic disintegration of the girl’s lovely, if secondhand, face. “Spots of pigmentation,” then “small subcutaneous nodules.” A few days later, “necrosis of the graft tissue”—then “ulceration”—and, finally, removal of the dead graft tissue and resumption of the hated mask. It is a setback that Christiane cannot endure, this corruption of her new face, and so the endgame is set in motion, the final struggle of the good daughter and her evil father.

Franju is consistently skeptical toward those—and not just the scientist—who put their faith in reason alone. The detectives trying to crack the case of the missing girls victimized by the doctor will completely misread the evidence in front of them, as will Jacques, Christiane’s young fiancé, who works as a doctor in Génessier’s clinic. A more conventional horror film might have allowed these men to destroy the monster and rescue the girl. Not this one.

A large part of the charm of the movie is the control of tone throughout. Its darkness, both literal and moral, never lets up. But there is also the subtlest flavoring of black humor, which lends a certain curious lightness of touch to the unrelenting negativity of the vision. It is there in the almost parodic use of medical terminology, in the hideousness of the surgical instruments, and even, in places, in the sly resonance of the imagery. A young woman is sent to the clinic as a kind of prey to trap the doctor, and while in bandages and surgical clamps awaiting her “face-lift,” she resembles nothing so much as an oddly distressed nun. She is, of course, one of the innocents and will escape the doctor, no thanks to the bumbling policemen. But the image of the nun anesthetized, festooned with clamps, feels mischievous even as it plays into the religious symbolism of the film, and a small, wicked chuckle can be heard within the swelling cacophony of its macabre denouement.

This is a story about the potential for evil of science in general and of medicine in particular, and not coincidentally it is also about patriarchy. It is about the father’s tyranny over his women. And it is hard not to speculate that Génessier’s increasingly frantic attempts to restore his daughter’s face might be read as the response of the abusive parent to his corrupted child. For the doctor was responsible—he was driving the car when the accident that disfigured Christiane occurred, and he always drove, she says, “like a lunatic.” So what we have is a lunatic father impelled to perform ever more desperate acts of violence to make his child good once more. The real horror in Eyes Without a Face is that Génessier is not motivated by love at all, but by his intolerable guilt at having ruined her.

This piece was originally included in the Criterion Collection’s 2004 DVD release of Eyes Without a Face.