“Welcome to the Realm of Imperfection”

A

t the San Francisco Silent Film Festival you can expect to see many great, even perfect, treasures of cinema, popular classics, and critical favorites. At the age of twenty-four, the event has become increasingly central to the silent cinema calendar—one of the most prestigious events of its kind in the world. It was founded in 1996 as a one-day event showing three films to a 1,500-strong crowd; now it welcomes about 25,000 people over five days each spring, and more to its Day of Silents in the winter. As well as screening movies with live music by some of the world’s best silent film accompanists, the festival has a close and fruitful relationship with international archives. The SFSFF works with these partners to create new restorations of films, and also highlights the work of scholars and preservations among its screenings. Watching a film here is not just a sensory immersion, but an education—as we learn about the journey of each title from its first run to its rediscovery—and often a voyage into the obscurer corners of cinema history.

Indeed what I found most captivating in the 2019 edition, held this May, was the presence of the shadows of the films themselves, the lost or censored reels, fleeting formats, and forgotten histories that make what remains simultaneously precious and enigmatic. From unrealized ambitions, latterly reconstructed, to cardboard ephemera that brought us closer to the novelty of cinema’s birth, the flaws, or rather the surprises, add to the enchantment. It was Gian Luca Farinelli of the Cineteca di Bologna, introducing a selection of shorts produced in searing Kinemacolor, who made the distinction between today’s films and the silent era archive. “We live in a world of digital perfection,” he said. “Welcome to the realm of imperfection.”

It’s not the films themselves that are imperfect—although Farinelli was referring to a glitch in some of the Kinemacolor films that revealed a full frame of red or green instead of the magical combination—but our sight of them, our access to them. It’s near-impossible to see these works exactly as they were made. Partly that is to do with the evanescent nature of a silent film screening: the live music and projection that can never be exactly repeated. At other times, it’s because restoration techniques can never quite undo the damage inflicted by time. By reproducing the delicate tints and accents of stencil color to Rapsodia satanica (1917), an ethereal Faust narrative starring the mesmeric Italian diva Lyda Borelli, restorers have allowed the film’s vibrant beauty to sing again. A sudden burst of print decay—white blotches on the frame—can’t detract from its singular gorgeousness, but instead acts as a reminder of the film’s archival status. For a silent film enthusiast, these moments provide a thrill akin to the return of a prodigal son, the recognition that this treasure might have been lost but is now saved.

The Cameraman

The Cameraman

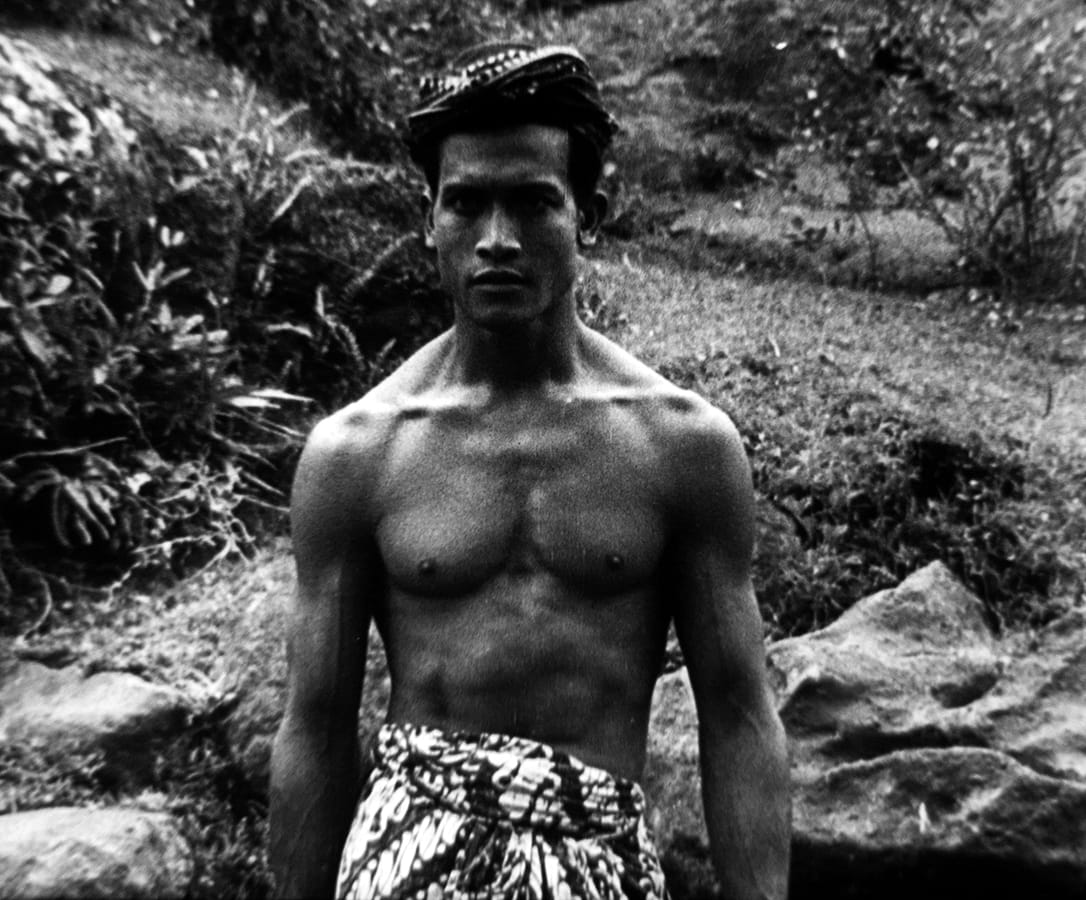

Goona Goona

Goona Goona

Opium

Opium

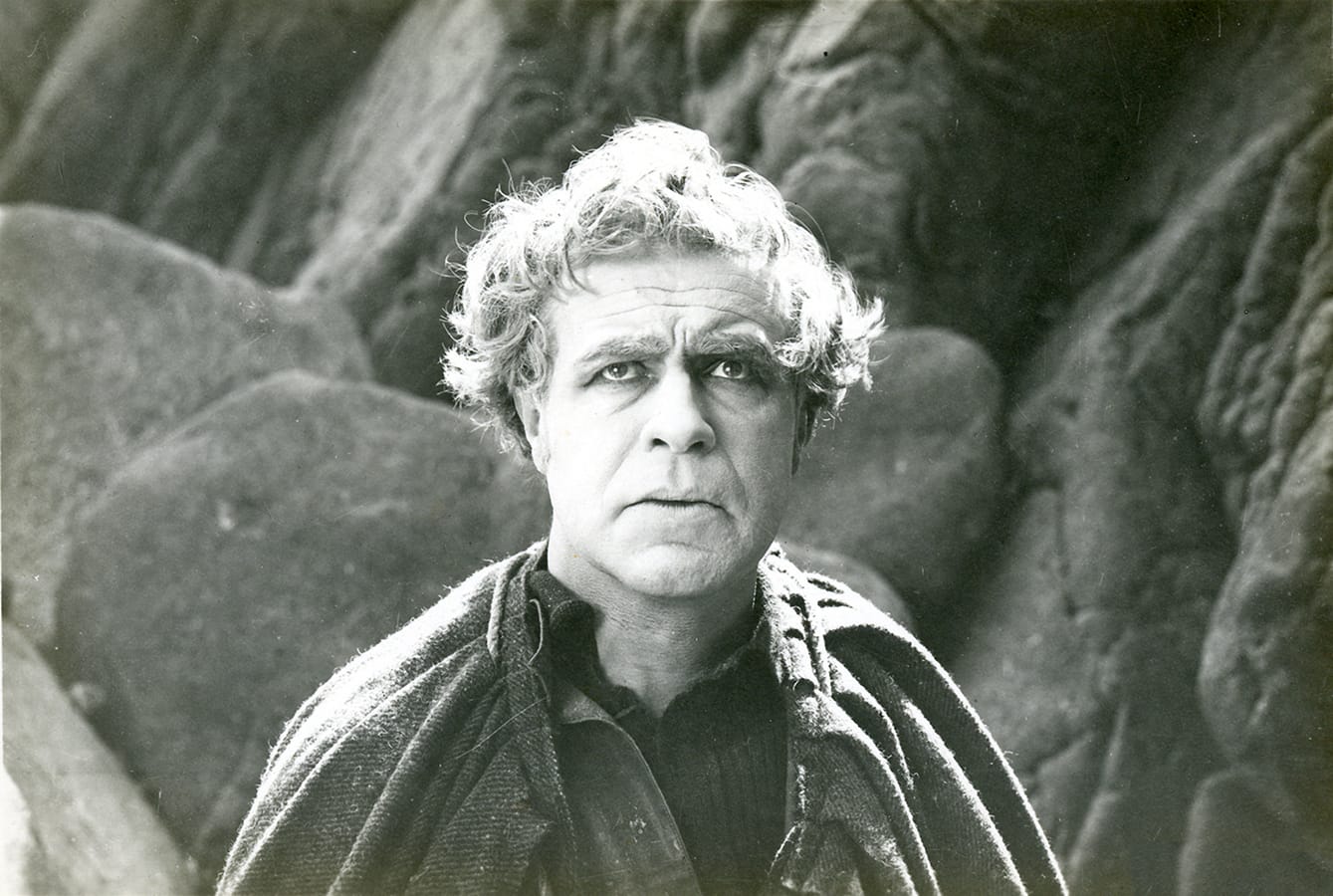

L’homme du large

L’homme du large

“My favorite restoration of the festival didn’t involve film at all, but some miniature ephemera, which were perhaps imperfect as moving images, but seductively tactile, and fragile, as artifacts.”