Ivan’s Childhood: Dream Come True

Andrei Tarkovsky’s objective in Ivan’s Childhood (1962) was, in his own words, “to establish whether or not I had it in me to be a director.” He succeeded brilliantly: this austere, minimalist, and poetic film was the first major accomplishment in an oeuvre that would become one of Russia’s main contributions to the treasury of world cinema.

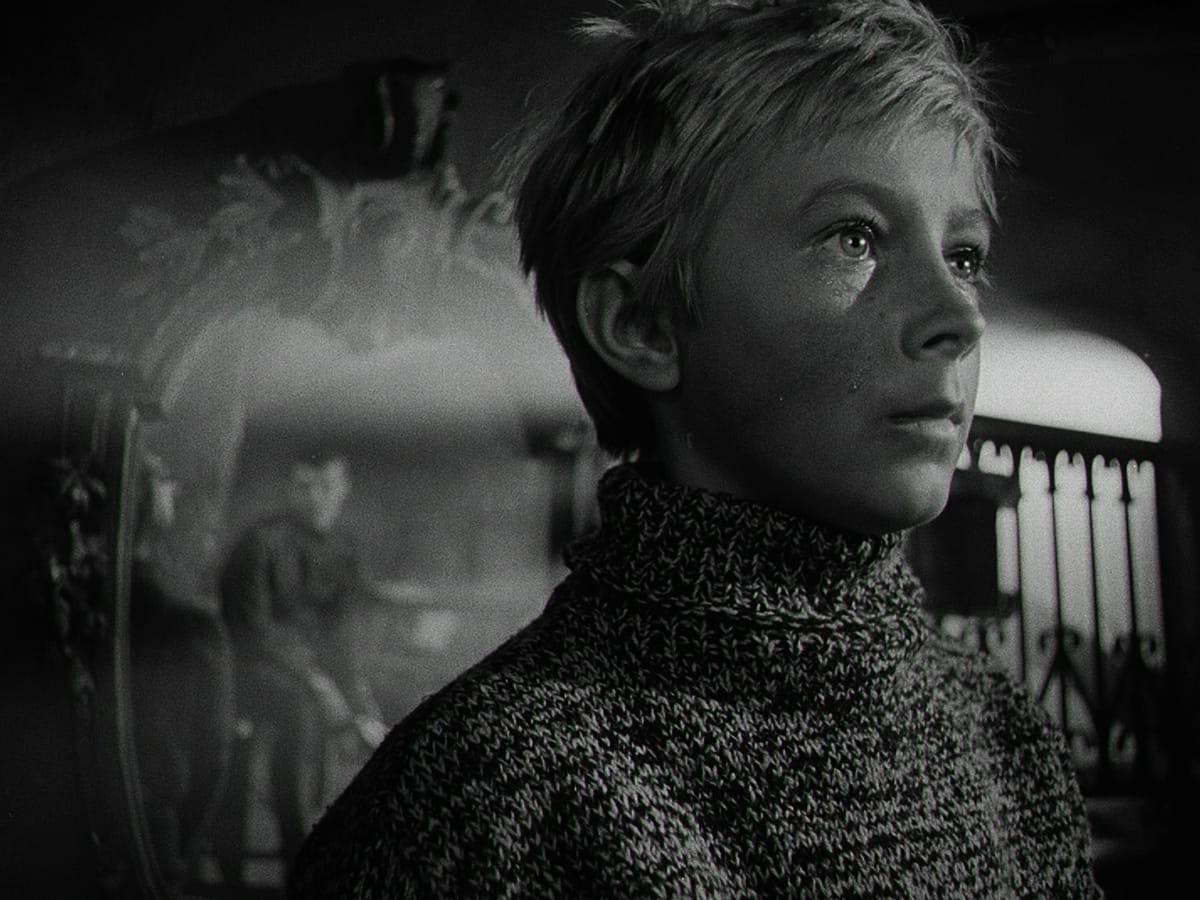

Not yet thirty years old, Tarkovsky had just graduated from VGIK (the Gerasimov All-Russian State Institute of Cinematography), the world’s oldest educational institution of its kind. Ivan’s Childhood had already been in development at Mosfilm but had been put on hold, so it came as a lucky break when the property was handed to Tarkovsky. The script was based on a novella by Vladimir Bogomolov but was reworked by Tarkovsky and his friend Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovsky (later an important Russian director in his own right, mostly known for 1979’s Siberiade). The fourteen-year-old Nikolai Burlyaev, who was cast in Konchalovsky’s debut short, The Boy and the Pigeon (1961), was selected to play Ivan.

It was natural for Soviet directors looking to break into the mainstream to make war-themed films. At the time, much of the official discourse on Soviet identity was still largely shaped by the shadow of World War II. Closely observed by the powers that be, war movies were the most likely type of film to be shown at international festivals and get proper distribution. But the new wave of war films differed from earlier socialist realist efforts, which mostly featured glorious Homo sovieticus fighting the Nazis under Stalin’s bright guidance, as seen in Mikhail Chiaurelli’s emblematic Fall of Berlin (1949). Beginning with Mikhail Kalatozov’s Cannes winner The Cranes Are Flying (1957), the most acclaimed war films of the period—which also included Grigori Chukhrai’s Ballad of a Soldier (1959), Sergei Bondarchuk’s Fate of a Man (1959), and, later, Rezo Chkheidze’s Father of the Soldier (1964)—moved away from combat and focused instead on the individual ordeals and suffering of those whose lives are irretrievably crippled by war. Ivan’s Childhood is remembered alongside those notable films of the short-lived thaw that broke out of the propaganda mold and gave war the face of true human anguish.

As the film opens, the twelve-year-old Ivan has already seen extensive violence and sorrow; the Nazi invasion has led to the death of every member of his family. He has been with the partisans and is already an experienced frontline scout for the Soviet army, sent ahead on risky reconnaissance jobs. Although just a skinny boy, he is stubborn and aloof and demands to be treated as an equal by his fellow soldiers, many of whom he has bonded closely with. Most of the film’s action happens over the course of two days: After Ivan returns from an assignment, there is talk of sending him away to the safety of a military school, yet he insists on continuing with his intelligence work. Before a clear decision is made, he is sent into enemy territory on yet another mission, from which he will not return.

Like Ivan’s, Tarkovsky’s childhood was spent during the war. “The most beautiful memories are those of childhood,” Tarkovsky noted, thus a number of private visions were brought into “the texture of the scenery.” In particular, he identified the images of the birch wood, the camouflage of birch branches on the first-aid post, the landscape in the background of the last dream, the lorry full of apples, and the horses wet with rain steaming in the sunshine as derived from his personal memories.

Tarkovsky’s debut has much in common with the works of his fellow Soviet filmmakers, and the influence that The Cranes Are Flying had on it is even greater than is generally acknowledged. For his graduation project, Tarkovsky had tried to approach The Cranes Are Flying’s legendary cameraman, Sergei Urusevsky, who had also shot Chukhrai’s austere revolution drama The Forty-first (1956). Urusevsky’s mastery of the camera greatly impressed Tarkovsky, and many of the decisions related to mise-en-scène, camera movement, and scene choreography in Ivan’s Childhood clearly follow the aesthetic model introduced by the cinematographer. Tarkovsky wanted the film to look as if Urusevsky had shot it, and his DP, Vadim Yusov, managed to accommodate him. Nearly every scene in Ivan’s Childhood is handled in a manner out of the ordinary, suggesting heightened consciousness of style, point of view, framing, and fluid camera. The complexly choreographed scene of Masha and Kholin’s encounter in the birch forest, for example, is constructed in a manner typical of Urusevsky: the shot begins from a low point of view, and then, when Masha tries to jump over the ditch and is intercepted by Kholin, who holds her in the air and kisses her, the camera goes down below ground level and records the scene from within the ditch, to soon thereafter rise sharply up and continue rolling at eye level with the characters.

More similarities can be easily found: negative images, similar to the white trees on the background of dark sky in Ivan’s third dream, were used by Urusevsky and Kalatozov in The Letter Never Sent (1959)—which is said to have influenced Francis Ford Coppola in his rendering of burning forests in Apocalypse Now (1979)—and would figure prominently in their amazing I Am Cuba (1964), two years later; a famous point-of-view shot in The Letter Never Sent , for which actress Tatyana Samoylova held the camera and shot her feet while running in a state of supreme anxiety, is replicated here at the moment when Masha runs looking for Galtsev between the birch trees; and the “drowned forest” through which Ivan makes his way on two occasions looks like the environment of Boris’s famous death scene in The Cranes Are Flying.

The cinematic influences of Ivan’s Childhood go far beyond its Soviet contemporaries, however. Polish filmmaker Andrzej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds (1958) seems to have had an artistic impact on the film, with its deep interiors lit by rays of light squeezing through cracks, its moments of veering consciousness, and especially its dislodged religious symbols placed amidst smoking ruins. Buñuel’s Los olvidados (1950), a critical realist film interweaving dream sequences, is a likely influence as well. Critics have also pointed to Dreyer, Bergman, Bresson, Dovzhenko, Welles, and Mizoguchi as visual antecedents.

Tarkovsky and Konchalovsky refashioned the story’s original plot structure by bringing to it a poetic dimension, mostly achieved by interplay between reality and dream. “Every time we tried to replace narrative causality with poetic articulation,” Tarkovsky said, “there were protests from the film authorities.” Nonetheless, the finished film is structured around four dream sequences and one episode of nightmarish daydreaming.

Ivan’s first dream presents a fairly uncomplicated, idealistic picture of carefree childhood—he is busy chasing butterflies, admiring shiny spiderwebs, running around barefoot, and being caressed by sunshine and by his mother. This dream does not have much of the specific surrealist quality that marks the others. Its function is to provide a contrast to the protagonist’s harsh awakening into the cruel reality of war—the child’s unscathed inner core versus a shell-shocked daily existence.

The second dream is important in the context of Tarkovsky’s entire oeuvre, as well as conveying key narrative information about the mother’s loss. Ivan returns from the mission, eats silently, and then falls asleep. From a close-up of the sleeping boy, the camera moves to the left, traveling over the fire nearby and then down to the floor, looking at his shoes and scattered pieces of wood. The sound of water drops provides a soothing background on which the camera cuts to a close-up of Ivan’s hand hanging out of the bed, with water flowing off his fingers. The camera then moves left again, but now looks up to show a square light spot at the top of a well, where Ivan and his mother are seen leaning over and looking down as a feather descends into the deep, dark pit. At the bottom one can see the reflection of a star, which Ivan reaches for. Suddenly, he finds himself down in the well, trying to catch the star. The rope of the pail quivers perilously as someone glances from the top; the pail is hurriedly pulled out, one hears remote, agitated voices, then the pail plummets down abruptly, followed leisurely by the mother’s scarf. Ivan shouts, “Mama!” with terror in his voice, and the next image shows water being splashed over the mother’s body, lying facedown on the ground next to the well. Relying on vertical movement, the dream’s mise-en-scène arrangement will become a key element in Tarkovsky’s later, visually dialectical style, which often prefers to show protagonists twice in a scene, from perspectives above and below, both within a situation and observing it from the outside.

The third dream is the most elaborate, and critics have seen its symbolism (the lorry’s overload of apples, the dramatic white trees on a background of stormy dark sky, and the horses that eat the spilled apples on the beach) as somewhat overstated—despite Tarkovsky’s insistence that he prefers his associative collages to be seen as metaphorical expressions of a self-contained reality and not as symbolic. The image of the little girl that keeps returning into the frame, every time with a more apprehensive expression, was meant to capture “the child’s foreboding of imminent tragedy,” Tarkovsky indicated.

The last dream occurs only after Ivan’s death, thus asserting Tarkovsky’s view that it is not linear logic but poetic linkages that matter for a truly graceful cinematic narrative. But who is dreaming it? “It is almost as if Tarkovsky transfers the burden of this dream onto the audience,” Vida T. Johnson and Graham Petrie assert in The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, “forcing us to fill in for the experience that Ivan can no longer have for himself and providing for us—but not for him—a sense of potential harmony and reconciliation that reminds us all the more cruelly of what he has lost.” This last dream—showing children playing on the beach, among shiny splatters of water, and the mother, who smiles and walks away into the distance—is permeated with splendor and innocence. The final shot is of Ivan, running through shallow water and nearly colliding with a menacing dry tree, a forbidding encounter that puts a sudden end to a truly tranquil bliss. Like the abrupt shadow of the tree that cuts his run short, Ivan’s life is cut short by the war, which, as the official Russian narrative of World War II has it, befell them unawares.

Ivan’s Childhood won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, thus giving Tarkovsky international visibility. The Italian Communist press, however, accused the director of overplaying the lyrical elements and substituting detached bourgeois aestheticism for class-consciousness. Meanwhile, Jean-Paul Sartre came to Tarkovsky’s defense, in a long letter to the editor of the journal L’unita, praising the style of the film and attacking the dogmatism of leftist film criticism.

Working on Ivan’s Childhood helped Tarkovsky articulate some of the important ideas he would later develop in his book Sculpting in Time. It is in connection with this film that he first spoke against the logic of “linear sequentiality” and in favor of heightening feeling through poetic connections, of using “poetic links” to join together film material in an alternative way that “works above all to lay open the logic of a person’s thought” and that is best suited for revealing cinema’s potential “as the most truthful and poetic of art forms.” Ivan’s Childhood, Tarkovsky noted, “helped to form my views.” And indeed, important elements of his later style are already present here in what would become his trademark imagery (horses, shallow water), tropes (a view over the protagonist’s shoulder while looking at a book of engravings; a loving yet withdrawn mother), and methods (trancelike visions; ostensibly unrelated yet commanding documentary footage). The disturbing episode of Ivan’s nightmarish vision in the bunker is a key link to the director’s later work: while in this early film the poetic instances are mostly confined to the space of dreams, later on Tarkovsky would have his protagonists veer away while awake (Solaris, from 1972; Stalker, from 1979). The director has repeatedly stated his preference for black and white, yet this remains his only truly monochrome film, using the contrast of light and darkness in poorly lit interiors.

As Ivan’s Childhood was the result of so many of Tarkovsky’s influences, so it had a profound effect on film history, as well. Impressions of it run far and wide throughout Eastern European cinema, from such specific films as Larisa Shepitko’s austere The Ascent (1976) and Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985), which has often been described as the most powerful Soviet war film, to the work of Sergei Paradjanov, who has explicitly acknowledged the impact of Ivan’s Childhood on his general oeuvre. Further afield, the birch forest love encounter was replicated by Miloš Forman in Loves of a Blonde (1965), while the film’s aesthetics influenced the overall style of one of the finest Yugoslav partisan films, Three (1965), by Aleksandar Petrovic. Connoisseurs of American cinema have claimed that the birch forest scene from Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995) is a direct homage to Ivan’s Childhood; others say that Star Wars’ Anakin Skywalker is modeled after Ivan. The only direct continuity that I have been able to establish with certainty, however, is the literal restaging of several of the film’s scenes in Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1995).

Tarkovsky went on to make a succession of internationally admired films. Toward the end of his career, he enjoyed unchallenged sovereignty over the throne of European art-house cinema—due to works like Andrei Rublev (1966), Solaris, Mirror (1975), Stalker, Nostalghia (1983), and The Sacrifice (1986)—before dying of cancer, at age fifty-four, in Paris. More than twenty years after the director’s death, the unassuming Ivan’s Childhood remains one of his most beloved films, and perhaps his most accessible. Those who know the director’s later work take particular pleasure in revisiting Ivan’s Childhood again and again, as it provides ample opportunity to see the early stirrings of Tarkovsky’s genius.